From the Chicago Reader (June 30, 1989). I reviewed the film a second time several weeks later, and this second piece will be reposted tomorrow (i.e., December 4, 2021).. — J.R.

DO THE RIGHT THING **** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Spike Lee

With Danny Aiello, Ossie Davis, Ruby Dee, Richard Edson, Giancarlo Esposito, Sam Jackson, Joie Lee, Spike Lee, Bill Nunn, Rosie Perez, John Savage, and John Turturro.

I can’t say that I’ve been an unqualified Spike Lee fan. His flair for publicity has tended to overwhelm his talents as a writer-director-actor, and the fact that he remains better known to the general public for his TV commercials than for either She’s Gotta Have It (1986) or School Daze (1988) points to an adeptness at working both sides of the street that has made it difficult to assess his work. More generally, the fact that he’s a black filmmaker whose first two features had all-black casts has undoubtedly made him overrated in some quarters and just as surely underrated and/or misunderstood in others.

She’s Gotta Have It, shot in only 12 days on a $175,000 budget, had some genuine virtues — likable lead performances, energetic dialogue, and Ernest Dickerson’s striking black-and-white cinematography. But the entire conception of a predatory lesbian character named Opal Gilstrap (Raye Dowell) was gratuitously nasty, and the breezy plot and (mainly) one-note characters had a thinness overall that made the movie recede in memory almost as soon as it was over.

School Daze was much more ambitious: it tackled a bigger subject (the volatile political dissensions and caste distinctions at a black college in Atlanta) and was stylistically audacious, attempting to frame the subject in the context of a musical comedy. But even here, one finally had to acknowledge the discrepancies between the movie’s bold aims and its actual achievements. Although the material was undeniably fresh, one had to contend with musical numbers that lacked both polish and electricity, choppy continuity, and an overall hit-or-miss quality in both the direction and the unwieldy script.

Neither of these features really prepares one for the quantum leap of Do the Right Thing, easily the best American movie released so far this year. It’s virtually the only summer release to date that honors its audience by asking it to think — without for an instant relinquishing its capacity to amuse and enlighten. If, loosely speaking, She’s Gotta Have It sacrificed content to style and School Daze sacrificed style to content, style and content in Do the Right Thing are joined seamlessly and effortlessly.

Restricting its action to one very hot summer day on a single block — Stuyvesant Avenue between Lexington and Quincy in Brooklyn’s Bedford-Stuyvesant — the movie is first of all the ensemble piece that Lee attempted in both of his earlier features; his handling of the actors here marks him as a consummate pro. It is also a complex, multifaceted statement about racism, with none of the simpleminded complacency or patronizing moralism of a Mississippi Burning — a street-smart movie without heroes or villains that manages to look at social process with a great deal of intelligence and understanding.

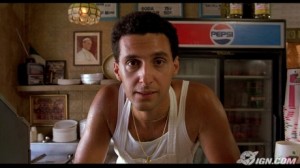

Crucial to the movie’s success is a dialectical presentation of the neighborhood and its options that refuses to limit the film’s viewpoint to that of any single character. The character Lee plays here, a pizza delivery boy named Mookie, is more central than his characters were in She’s Gotta Have It and School Daze. But Mookie’s viewpoint is not that of the film — indeed, the whole point of the movie’s title is that “Do the right thing” means something different to every character. Like Half-Pint in School Daze, Mookie is positioned literally at the crossroads of the movie’s major conflicts; like Lee himself, he works both sides of the street — a living embodiment of the dialectical principle. But he is no more a spokesperson for the film’s viewpoint than anyone else is.

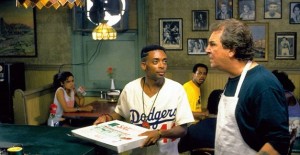

The film as a whole charts the accumulation of small racial incidents that eventually explode into violence — a seemingly plotless succession of events that is actually tightly and purposefully constructed. Significantly, the three black characters who play the most substantial roles in precipitating the conflict–Buggin Out (Giancarlo Esposito), Radio Raheem (Bill Nunn), and Smiley (Roger Guenveur Smith) — are all outcasts from the black community. Each one has a semilegitimate gripe, however, and each one has been goaded to some extent by Sal (Danny Aiello), the owner of the local pizzeria, by his racist son, or by both. But it’s part of the brilliance of Lee’s script that one can’t summarize what leads up to and intensifies the violence without recounting practically everything that happens in the film.

The fact that Do the Right Thing is not, strictly speaking, a realistic movie is equally important to its strategy. Lee clearly knows his elected turf like the back of his hand, and many of the neighborhood characters seem to be drawn directly from life — such as the stuttering Smiley, the trio of very funny kibitzers who sit around all day commenting on the passing parade (Robin Harris, Frankie Faison, and Paul Benjamin), and a couple of older spectators, Da Mayor (Ossie Davis) and Mother Sister (Ruby Dee). But Lee interprets this knowledge using a variety of movie conventions; his portrait of the ethnic neighborhood is functional to the movie’s design, but far from exhaustive. One of his more whimsical departures from realism occurs during a pan across some newspaper headlines. It’s plausible that the New York Post would proclaim “Phew!” but the New York Times declaring “Yes, It’s Hotter and Muggier and You’re Going Crazy!” is an idea more likely to be found in a Tex Avery cartoon.

Some commentators have already remarked that there are no drugs and no allusions to drugs in the film. There were also none in Lee’s previous features; She’s Gotta Have It even included a title at the end of its final credits: “This film contains no jerri curls!!!! and no drugs!!!!” Lee has rightly pointed out that no one would think of criticizing a movie set on Wall Street for excluding drugs: our usual demands about “realism” frequently have double standards and hidden agendas. (It’s worth noting in passing that the film crew on Do the Right Thing managed to shut down the crack houses on the block for the eight weeks of shooting. Still, as some local residents suggest in St. Clair Bourne’s excellent documentary Making “Do the Right Thing,” there’s no reason to assume that the crack dealers wouldn’t — or didn’t — resume their trade after the film crew moved on.)

The movie’s dialectical construction and its nonrealistic approach are both highlighted at the outset. The picture opens with Tina (Rosie Perez), one of the leading female characters, dancing to Public Enemy’s “Fight the Power” on what is clearly a soundstage version of the story’s setting. Tina is dressed at separate points first as a boxer, then in a red dress, and later in blue tights. The blatant unreality here, which remains an implicit reference point throughout the film, doesn’t in any way detract from the superreality of the movie’s theme; it’s merely an indication that the viewer is being asked to assume a thoughtful and analytical as well as emotional relation to what’s going on.

This is equally true of the movie’s dialectical conclusion. The film ends with two pertinent quotations as on-screen titles — one from Martin Luther King about the impracticality and immorality of violence, and one from Malcolm X about the practicality and “intelligence” of self-defense — followed by a photograph of the two black leaders together, which has previously played a pivotal role in the movie’s plot. While it would be much too pat to say that Tina with her boxing gloves at the beginning “stands for” Malcolm X while her less combative dancing in more middle-class attire “stands for” King, the dialectical significance of such pairings shouldn’t be overlooked. In her red dress and blue tights, Tina resembles Jade, Mookie’s sister (played by Joie Lee, the filmmaker’s sister). Jade is upwardly mobile: respected, treated like a queen by Sal at his pizzeria, and closer than any other black character in the film to the middle class. Tina herself, who’s Mookie’s Puerto Rican girlfriend and the mother of his son Hector, is fiercely working-class, angry and volatile, and even further from middle-class assimilation than Mookie is. Part of the movie’s density is the result of its alertness and sympathy to both sides of both dialectics — not making a choice between classes or between King and Malcolm, but understanding and appreciating what all might have to say.

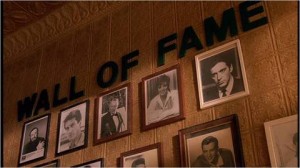

Variations in this pattern of contrasts can be seen and felt throughout the film. Sal has two sons who work with him at the pizzeria: Pino (John Turturro) is sour and racist, and Vito (Richard Edson) is sweet and accepting; together they suggest the two sides of their father’s personality. The two businesses on the block, directly across the street from each other, both cater mainly to blacks and Hispanics and are run by neither blacks nor Hispanics — Sal’s pizzeria and a Korean grocer. One major point of dispute, a pet peeve of Buggin Out’s that eventually leads to violence, is that Sal’s Wall of Fame — a gallery of photographs of famous Italian-Americans on the wall of his pizza parlor — doesn’t include any blacks. In keeping with the film’s thematic intricacy, local DJ Mister Senor Love Daddy (Sam Jackson) at one point offers his own Hall of Fame on his radio show — an extended, reverential list of famous black musicians and singers — although the connection between this Hall of Fame and Sal’s is never made explicit.

The status and behavior of individual characters also change dialectically. Da Mayor initially appears to have the lowest standing of any member of the black community — he’s a burly alcoholic treated affectionately by the film, much as Alan Hale was in Raoul Walsh’s The Strawberry Blonde (1941). But Da Mayor winds up saving the life of a ten-year-old boy who nearly gets run over, and he gradually emerges as something very much like the community’s patriarchal conscience and guru. Da Mayor’s ambiguous romantic relationship to Mother Sister runs through a comparable spectrum. Two white cops who are brutal and punitive toward local blacks during the film are shown to have been relatively mild and lenient in an earlier racial incident.

Karl Marx wrote in The 18th Brumaire of Louis Napoleon, “Hegel remarks somewhere that all facts and personages of great importance in world history occur, as it were, twice. He forgot to add: the first time as tragedy, the second as farce.” One of the more clever organizing principles of Do the Right Thing — which lulls the audience into thinking they’re watching a straight comedy, giving the eventual cataclysm greater force — is to invert Marx’s dialectical formula, so that what initially figures as farce often comes back as tragedy.

The point of all this duality is that, when it comes to understanding the day’s events, Lee isn’t taking sides — and he isn’t asking us to, either. This doesn’t mean that he treats Pino and Mookie, for example, with equal sympathy, but it does mean that he sees both of them clearly and objectively. A lighter ensemble piece featuring blacks, Car Wash (1976), was content to reduce its white characters to satiric if affectionate stereotypes, slyly reversing the usual treatment in most Hollywood pictures. Do the Right Thing avoids racial stereotyping altogether, and is generous enough to give every character his or her due — without ever losing sight of anyone’s shortcomings. (Ironically, Sal emerges as the most complex character in the film; if Aiello has ever given a better performance, I haven’t seen it.)

Unlike the grander ensemble piece Nashville (1975) — which singer Brenda Lee once astutely described as “a dialectical collage of unreality” — Lee’s movie eliminates condescending ridicule as well as platitudes from its basic vocabulary. Nashville‘s major platitude — the “truth” meant to subsume every aspect of its pluralistic vision — was the American flag. It plastered this flag across the screen in the closing sequence as if this were some guarantee of cosmic significance: not so much a final statement as a portentous substitute for one. The equivalent image in Do the Right Thing is the photograph of Malcolm and King, and Lee uses it not as an image of closure but as a dialectical starting point, a place to begin. The last time that we see this photograph in the story proper, Smiley has just triumphantly and pathetically posted it to the wall of the looted, gutted, and burning pizzeria. When it appears again after the quotations, it becomes a moving emblem of the future as well as the past.

Formal dialectics enter into the way Lee handles framing, camera movement, and editing. A majestic crane shot moving out the window of the radio station of Mister Senor Love Daddy, whose droning patter drifts through the community like the strains of a Greek chorus, helps to emphasize the way his messages are connected with the world outside. By contrast, a quick, comic succession of close-ups showing several characters spewing racial and ethnic epithets directly to the camera, orchestrated like a piece of music, abruptly atomizes the community into a collection of discrete, isolated units. (Pino: “You gold-teeth, gold-chain-wearing, fried-chicken-and-biscuit-eatin’ monkey, ape, baboon, big thigh, fast-running, high-jumping, spear-chucking spade moulan yan.” Mookie: “Dago, wop, garlic-breath, pizza-slinging, spaghetti-bending, Vic Damone, Perry Como, Luciano Pavarotti, solo mio nonsinging motherfucker.”) The latter sequence is a brief, indulgent fantasy — all of the characters are framed in separate locations, addressing no one in particular, shortly after being seen in social contexts — and the staccato editing helps to point up their comic similarities as well as their isolation.

Elsewhere, Lee makes a sharp distinction between social confrontations that are charted with a moving camera and those depicted through reverse-angle editing. Radio Raheem, who stalks through the film with brass knuckles labeled “love” and “hate” (a specific hommage to Charles Laughton’s Night of the Hunter capped by Raheem’s recitation of Robert Mitchum’s “sermon” in that film about the two words tattooed his knuckles), repeatedly plays “Fight the Power” on his ghetto blaster. At one point he encounters a few Hispanics blasting Latino music on their radio. There’s a duel between the two kinds of music as the volume levels are turned up on both radios — a moment of tension that eventually gets resolved when Raheem walks away. By panning back and forth between the radios and their owners throughout this standoff, Lee encloses this incident in a single take and suggests that whatever the differences between Radio Raheem and the Hispanics, they are still coexisting in the same universe. And during the climactic racial incident, Mookie is goaded into action by several friends whose separate remarks to him are conveyed directly to the camera in a single extended pan, in a shot that resembles the TV interviews of soldiers in Full Metal Jacket. Both these examples, as well as the crane shot moving from the radio station to the street, imply that the moving camera delineates an unbroken flow of communication.

But when the confrontations become racial rather than cultural or ideological, Lee cuts back and forth between the antagonists, isolating each in a separate shot and frame. At a climactic juncture, also involving Radio Raheem, he frames the separate antagonists in tilted angles, creating a sense of spatial imbalance that implies not a dialectic but a morass, a precipitous incline down which both parties are sliding even if they’re coming from separate directions.

Nothing about Lee’s stylistic maneuvers is schematic or forced; most of them are so well integrated with the dramatic shapes of separate scenes that it takes an act of will to tease them out of their contexts. Just about the only awkward and contrived moments derive from some overly busy, distracting stretches in the film’s virtually wall-to-wall score, composed by the filmmaker’s father, Bill Lee. The problem isn’t so much the music itself as the often redundant functions it is called upon to serve (which also happened with Bill Lee’s similarly omnipresent score for School Daze). Ossie Davis and Ruby Dee conversing on a stoop are touching enough without Hollywood-ish strings churning out a sappy tune evocative of Stephen Foster, and the music behind the crucial final dialogue between Mookie and Sal is even more gratuitous. Given that Spike Lee’s next project, A Love Supreme, is about a jazz musician, one hopes that he’ll get a better handle on how to use music more sparingly.

This flaw apart, Do the Right Thing doesn’t take a single false step — though the action it describes seems little more than an accumulation of countless false steps on the part of an entire community. Within the terms established by the movie, everyone is partially wrong and partially right, evoking laughter as well as tears; and working both sides of the street, Spike Lee manages to see it all happen.