From the June 10, 1994 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

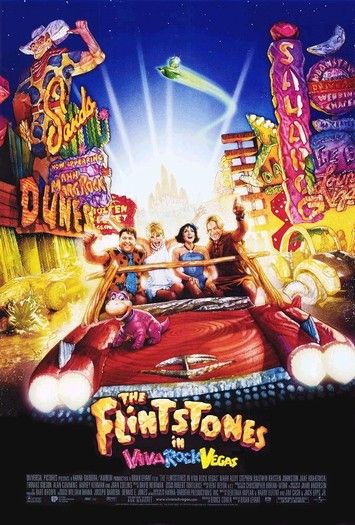

THE FLINTSTONES

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Brian Levant

Written by Tom S. Parker, Jim Jennewein, and Steven E. de Souza

With John Goodman, Rick Moranis, Elizabeth Perkins, Rosie O’Donnell, Kyle MacLachlan, Halle Berry, Richard Moll, and Elizabeth Taylor.

When people come to see an entertainment based on another, earlier entertainment that they have affection for, there are things about it that people want to see. They want to hear Fred yell “Yabba-Dabba-Doo!” They want to hear Wilma and Betty say “Charge It!” They want to hear Dino bark “Yip, Yip, Yip, Yip, Yip” and knock Fred down and lick him silly. And we’ve done those things because we love them, too. — Brian Levant, director of The Flintstones, quoted in the film’s pressbook

It’s quite possible that when someone writes the history of the first hundred years of movies — a period corresponding fairly closely to the 20th century — two decades of that century will be singled out as the most artistically barren: the first and the last. And the principal reasons for that barrenness may turn out to be related: in each decade film, rather than flexing its muscles as an expressive medium, was a relatively inert, inexpressive receptacle for works already fashioned, often in other media.

In 1908, when France was still the country that dominated the international film market, a company was founded calling itself the Societé Film d’Art. It was devoted to transferring prestigious stage plays with famous actors to the screen, plays filmed from one unvarying camera position. The first of its countless productions, L’assassinat du duc de Guise, is unwatchable to everyone but specialists today, but it was hailed at the time as a major cultural event, a turning point in the so-called art of cinema. This was well before the perception that camera placement and editing have moral and aesthetic consequences in such an art.

In 1991, when the U.S. was comparably dominant in the world film market and TV had long since supplanted film as the central medium, Terminator 2: Judgment Day became the first feature to employ morphing — a digital video technique allowing one pixel to replace another within a single continuous take. The most I can make is an educated guess, but it seems to me that the supposedly liberating technique of morphing may well prove to be the most aesthetically and morally crippling innovation in the history of movies so far — not only because it makes lying much easier but also because it removes another reality check from our consciousness. Thanks to morphing, anything can happen in a shot regardless of whether it happens in front of a camera; but there is no new ethic or aesthetic available to help us determine whether it should happen, or what the consequences will be if it does. One response to this quantum leap in freedom, it seems to me, is a frightened retreat to the tried-and-true, an even more determined move toward the compulsive recycling of familiar materials.

Oddly enough, these two events — the launching of so-called films d’art and the introduction of morphing — can be regarded as complementary and in some ways even comparable in implications as well as in effects, despite the fact that they imply antithetical definitions of what movies are. L’assassinat du duc de Guise implies that a film is simply whatever happens in front of a camera — in this case, a work of art from another medium. Terminator 2 suggests that what happens in front of a camera is ultimately irrelevant, at best secondary.

Both events say in different ways that film can be anything and everything; but each anything and everything occurs in a philosophical void. It seems fitting that the films’ titles point toward death and apocalypse. The content of L’assassinat is high art and the content of Terminator 2 is low art, but in terms of film art these movies can be defined only negatively and passively, as indifferent receptacles for old materials.

For audiences of films d’art in the 1900s film was just an excuse for other artworks, and for audiences of Hollywood pictures in the 1990s film is mainly an occasion for revamped versions of things we’ve seen before, most often on TV and video. The Flintstones appears alongside Maverick, another TV spin-off, and when I caught up with it last week it was preceded by trailers for The Shadow, The Little Rascals, Baby’s Day Out (hawked as a Home Alone variant), and Radioland Murders (which both looks and sounds like a cross between Radio Days and Manhattan Murder Mystery). At the Cannes film festival last month, everything that received the most attention was déja vu: this year’s French big-budget literary monolith (La reine Margot), the third parts of trilogies by Kryzstof Kieslowski and Abbas Kiarostami, a Zhang Yimou feature (Lifetimes) plowing much the same territory as Farewell My Concubine and The Blue Kite, a French counterpart to The Player (Michel Blanc’s Grosse fatigue), and so on, with the top award going to this year’s flaky-violent Hollywood postmodernist extravaganza, Pulp Fiction — an equivalent to Wild at Heart and Barton Fink, two other 90s noirish comedy-thrillers dripping with film references and racial slurs that previously copped the same Cannes prize.

Never having seen The Flintstones as a TV cartoon show, I looked forward to the remote possibility of the movie having something at least slightly fresh to impart. Bill Hanna and Joseph Barbera, who produced the show’s 166 episodes between 1960 and 1966, seemed to be the K mart kings of cheap, meat-and-potatoes animation, from Tom & Jerry to Huckleberry Hound, but maybe, I figured, a live-action movie from Steven Spielberg’s company based on the cartoon series would do something a little different. Unfortunately, I’d forgotten what decade I was living in.

In fact, The Flintstones is more encrusted with compulsive, cutesy familiarity than any big Hollywood movie I’ve seen this year. The morphing that is essential to the movie’s overall texture only makes The Flintstones that much more so. It’s used most noticeably in the animation of prehistoric creatures — a central gag is Fred Flintstone’s garbage disposal unit, a “pigasaurus” that lives under his kitchen sink — but it’s also evident in countless fleeting effects, such as the metamorphosis of a smoke ring into a dollar sign.

The unvarying sitcom pacing of the dialogue is relieved only by the equally unvarying music-video pacing of the leaden sight gags. If the characters are all hand-me-downs from The Honeymooners and I Love Lucy, the jokey décor and background detail seem like third-generation Xeroxes from Li’l Abner (both movie versions as well as the comic strip) and A Funny Thing Happened on the Way to the Forum (the movie) decked out with southern California’s architecture and exterior night lighting.

As in the equally TV-driven The Addams Family — but unlike the superior Addams Family Values, which scared off the mass audience with its vindictive social satire — familiarity is the very essence of The Flintstones, its sole source of pleasure and comfort, its only route to its audience’s narcissistic self-recognition. The most banal and calcified aspects of American life as they’re perceived and received on television — even down to the commercials (reconfigured here as jokey product tie-in plugs) and such standbys as CNN and Jay Leno — are granted a dubious second life through the Stone Age context, occasioning a plethora of bad geological puns and an endless reshuffling of complacent TV tropes and archetypes.

The point of these cardboard archetypes, which all once had some validity and truth in their original incarnations — perhaps for all I know even in the TV cartoon series — is that they’re ultimately interchangeable with the prehistoric creatures brought to life in the film through morphing. They seem to exist in a twilight stage of semiexistence, not because anyone in the audience still believes in them but because everyone recognizes them as emblems of their couch potato past. (“Gee — I once saw that on TV.”) In this respect, they differ radically from the sincere if corny archetypes in a movie like Casablanca, which, as Umberto Eco once noted, “became a cult movie because it is not one movie. It is ‘movies.’ . . . When all the archetypes burst out shamelessly, we plumb Homeric profundity. Two clichés make us laugh but a hundred clichés move us because we sense dimly that the clichés are talking among themselves, celebrating a reunion.”

The reunion Eco is talking about could only take place because of a shared social reality — not just between the actors on-screen in Casablanca but between those actors and the audience, everyone experiencing at that juncture (1942) the same global war and its effects. But what is there to share in The Flintstones between morphed animals who never existed and actors impersonating cartoon figures, much less between those human and nonhuman elements on the screen and the audience? If we stick to just the human beings on both sides of the screen (which leaves out a great deal), all we have by way of shared experience is a marketplace channeled through TV — goods for sale that ultimately include performers and spectators as well as home furnishings and hamburgers. Whether we buy or sell (or are sold or bought), our sole common bond becomes the fact that we somehow participate in these transactions. Fred Flintstone leaping into the air and magically hovering there, whether he’s a cartoon figure or a performing actor, comes closer to a smoke ring turning into a dollar sign than he does to Ingrid Bergman saying, “Play it again, Sam.”

The moral and philosophical chaos lying at the heart of such light entertainment, once people become interchangeable with objects, is aptly spelled out by a statement ascribed to Elizabeth Perkins (Wilma Flintstone) in the movie’s press materials. It deserves quoting in full. (Whether such a statement actually comes from Perkins herself or from a publicist-ventriloquist is not important.) Compare the first paragraph to the second and you have all the makings of a full-blown schizophrenia:

“One of the things that Brian Levant pushed us towards was to make these real people with real feelings and real emotions and real love,’ Perkins explains. “As much as you can get the look down and get the walk and the hair and the voice and the make-up, it has to be really grounded in some kind of reality or else it’s just an impersonation.’

“‘The goal of playing Wilma is to be true to the cartoon,’ adds Perkins. She studied hours of Flintstone episodes to master the physical aspects of the role and emotional tone. ‘She had a very distinctive way of carrying herself,’ Perkins observes. ‘One of the things that’s really recognizable with Wilma and Betty is that everything they do, especially when they stop walking, their bodies go into poses — almost like mannequins.'”

Real people with real feelings and real emotions and real love who are true to cartoons and slide into poses almost like mannequins: the description is supposed to apply to actors in The Flintstones but I think it also applies pretty well to people who watch the movie and force themselves to laugh occasionally at its lame jokes, myself included. Through the miracle of movies, we all join the The Flintstones in becoming living, breathing, snorting garbage disposal units.