From the Chicago Reader (July 2, 1999). — J.R.

Run Lola Run

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed and written by Tom Tykwer

With Franka Potente, Moritz Bleibtreu,

Herbert Knaup, Armin Rohde, and Joachim Krol.

A low-budget no-brainer, Run Lola Run is a lot more fun than Speed, a big-budget no-brainer from five years ago. It’s just as fast moving, the music is better, and though the characters are almost as hackneyed and predictable, the conceptual side has a lot more punch. If Run Lola Run had opened as widely as Speed and it too had been allowed to function as everyday mall fodder, its release could have been read as an indication that Americans were finally catching up with people in other countries when it comes to the pursuit of mindless pleasures. Instead it’s opening at the Music Box as an art movie.

Why try to sell an edgy youth thriller with nothing but kicks on its mind as an art movie? After all, it’s only a movie — a rationale that was trotted out for Speed more times than I care to remember. The dialogue of Run Lola Run is certainly simple and cursory, but it happens to be in subtitled German — which in business terms means that it has to be marketed as a film, not a movie. And of course nobody ever says “It’s only a film,” just as no one ever thinks of saying “It’s only a concert,” “It’s only a novel,” “It’s only a play,” or “It’s only a painting.” Because they’re omnipresent, movies almost oblige us to cut them down a peg or two just so we can breathe around them.

“It’s only a movie” is another way of saying “So what?” — a way of protecting ourselves from the high claims made for cheesy products shoved so aggressively into our lives. Nothing if not aggressive, Run Lola Run is a movie in every sense of the word, but our cultural planners have deemed that it has to wend its way toward us as a foreign picture. But foreign in what sense, particularly given its devotion to the Tarantino model of narrative organization? Frankly, the only thing that keeps it foreign is industry shortsightedness and perhaps our own knee-jerk responses.

Don’t be put off because Run Lola Run begins with two weighty quotes, one of them from the last of T.S. Eliot’s Four Quartets, “Little Gidding.” I didn’t quite catch what it said — the person seated in front of me decided to stretch at that point — but I can’t believe it has any serious bearing on what follows. I take it to be a quintessentially Germanic reflex gesture claiming some sort of significance, like the elaborate presentation of a Gothic clock that follows, or the pixilated city crowd that comes next, or the narration about “man” as “the most mysterious species on our planet,” which reminded me of Edward D. Wood’s early musings in Glen or Glenda? Yet the jazzy visual effects and punchy sounds accompanying the clock, the crowd, and the subsequent credits are the basic text here, and all the ponderous trimmings are basically fashion statements, not pertinent commentaries on what’s to come.

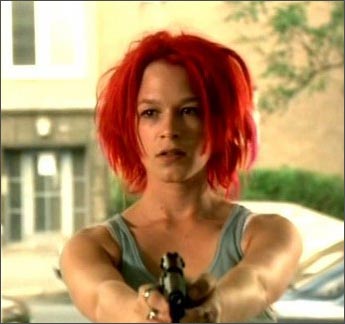

When the minimal plot finally slides into view, Lola (Franka Potente) — a Raggedy Ann punk with blazing orange red hair — gets a frantic phone call from her boyfriend, Manni (Moritz Bleibtreu). Some pithy flashbacks in black and white explain the cause of his panic: he just picked up 100,000 marks’ worth of drugs for his boss (Manni’s narrative), but she wasn’t there to pick him up because her moped got stolen (Lola’s narrative). So instead he took the subway, and his bag of drugs got lifted by a tramp (Manni’s narrative). It’s 20 minutes to noon, and his boss, who’s meeting him at noon in front of the phone booth he’s calling from, will kill him if he doesn’t have the 100,000 marks. His only recourse is to hold up a nearby supermarket.

She says she’ll get the money somehow and bring it to him in time. Tossing the red phone receiver into the air, she darts out of her apartment before it can land, whizzing past her mother. The camera spins 360 degrees around her mother to catch an animated cartoon on a TV set that shows a cartoon Lola running down the stairs, followed by a live-action Lola emerging from the apartment house and racing across town.

Most of the remainder of the movie gives us three successive versions of Lola’s 20-minute race against the clock, with radically different outcomes deriving in each case from various chain reactions as she runs across the city to her father’s bank. In the first two versions, for instance, she collides in a different way with a woman pushing a stroller, and the third time she just misses doing so. Waiting at the phone booth, Manni also goes through three alternate sets of adventures that are intercut with Lola’s progress. (Some less successful interludes — prefaced by the title “and then…” — offer rapid digressions about minor characters in the form of successive snapshots.)

Which 20-minute stretch “really” happens and which two are speculative? From the outset, writer-director Tom Tykwer makes such a question both unanswerable and meaningless. The arching trajectory of the phone receiver and the TV-cartoon Lola rushing down the stairs signal that this is theme and variations, a stylistic exercise, not even a loose approximation of anything that could conceivably happen to anybody. And this hyperbole only gives Tykwer further license to exaggerate one outrageous confluence or coincidence after another, confident that no one could object. Both the exhilaration and the hollow affectlessness of everything that follows proceed directly from this game plan. Given that “it’s only a movie,” the two qualities can even be said to fit hand in glove.

A few stabs at classification:

1. Run Lola Run belongs to a current international cycle of movies that ask the question “What if this succession of events happened differently?” Other examples include Sliding Doors, The Lovers of the Arctic Circle, and Twice Upon a Yesterday; more distinguished forerunners include It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), Rashomon (1950), Last Year at Marienbad (1961), The Exterminating Angel (1962), and Blind Chance (1982).

2. Run Lola Run is a game of narrative repetitions tied to a criminal plot involving a heist, robbery, and drugs — a tradition that can be traced through The Killing (1956), Reservoir Dogs (1992), Pulp Fiction (1994), Jackie Brown (1997), and the recent Go, among others.

3. Run Lola Run is a feature-length music video built on relentlessly pumping industrial music that mixes live action with animation and fancy visual effects with speed.

4. Run Lola Run is a fashionable youth picture about lovers on the run (the biggest cliché of them all).

Stylized continuous action has been a staple of movies from the beginning, and it might be argued that Tykwer is only giving us a late-90s version of something like Buster Keaton. This isn’t a baseless comparison insofar as the movie gets a certain amount of literal as well as figurative mileage out of the pleasure of watching Lola run. Yet as soon as the movie has to conjure up something resembling a world and a plot — or three separate worlds and three separate plots — the comparison starts to break down. No matter how fanciful and graceful Keaton got, he was always moving through a world and a plot that had a certain logic and fullness that wouldn’t allow for any cartoon substitutes. By contrast, the world of Run Lola Run is jerry-built, put together to produce certain momentary effects — a world in which Lola herself as a physical presence is no less disposable and malleable. You might say it’s a plot and a world that keep moving but wind up nowhere, since the three endings cancel one another out — a world where anything can happen and where, as a consequence, nothing matters.

I can’t tell you the first time someone said “It’s only a movie,” but I think I can pinpoint the first time it registered in the public consciousness: when Alfred Hitchcock quoted himself saying it. In François Truffaut’s book-length 1966 interview with Hitchcock the two men discuss Ingrid Bergman’s “harrowing memories of the way large pieces of the décor” would slide out of sight during some of the long takes in Hitchcock’s Under Capricorn (1949), his second color feature. “She didn’t like that method of work,” Hitchcock tells Truffaut, “and since I can’t stand arguments, I would say to her, ‘Ingrid, it’s only a movie!'”

That’s a significant precedent if one reads that phrase as a way of disparaging claims that movies are a serious art form. Back in 1949 Under Capricorn was a failed movie in the eyes of Hitchcock as well as his audience, “only a movie” in the worst sense of that term. A few years later it was passionately defended by Truffaut and some of his colleagues as a serious work of art, and last month in New York it was applauded as precisely that by many people who saw a new print at the Museum of Modern Art’s Hitchcock retrospective. But Hitchcock — a master throughout his career at making movies that were also films, entertainments that were also art — worked in an industry where it was expedient to disavow any artistic intentions. Like other industry expressions that have been picked up by the public at large, this self-deprecating directive has gradually been translated into a straight deprecation by viewers who resist accepting any deeper intentions or ambitions in movies.

Remember I’ll Do Anything (1994), the James L. Brooks musical comedy that lost all of its musical numbers as it got test-marketed, that was finally released in a form that pleased nobody? One of the best of the lost musical segments was a nicely choreographed dance number performed by acting hopefuls preparing for screen tests on a studio lot and chanting compulsively “You got to make believe” and “It’s only a movie” as if they were mantras. The “it’s only a movie” mantra appears to have persuaded Brooks to eviscerate his own work by eliminating this number and all the others after preview audiences didn’t respond in the correct Pavlovian manner. Of course anything can be eliminated once the “it’s only a movie” philosophy gets installed as a directive, including cheap thrills and the options of future audiences, not to mention the efforts of cast and crew. That philosophy came very close to eliminating “Over the Rainbow” from The Wizard of Oz after that song tested as badly as the musical numbers in Brooks’s movie, but some executive had the good sense to follow his own instincts.

“It’s only a movie” is an accurate phrase when it’s used to describe most movies we see, including Run Lola Run. It describes a lot of razzle-dazzle adding up to nothing — the essence of what the trade, and now the parroting audience, calls a summer movie. But when people use that same phrase to deny the seriousness of a body of work ranging from Keaton to Hitchcock, from Dreyer to de Oliveira, from Kubrick to Kiarostami, they become complicit in the industry’s rationalizing of seedy business transactions and irrational test-marketing practices.

And when that rationalizing starts shoving art movies out of art houses to make room for more no-brainers, the studios may think they’ve proved we’re just as stupid and undiscerning as they’ve claimed all along. Run Lola Run celebrates that stupidity with verve and energy; it’s guaranteed to keep you glued to your seat with your mind blissfully unoccupied. But at least for its conceptual kicks, it might have celebrated some form of intelligence if it were playing at 600 N. Michigan or at Webster Place, where the standards are usually lower.