Written for the May 2016 Artforum. — J.R.

Although Jacques Rivette was the first of the Cahiers du Cinéma critics to embark on filmmaking, he differed from his colleagues—Claude Chabrol, Jean-Luc Godard, Eric Rohmer, François Truffaut—in remaining a cult figure rather than an arthouse staple. His career was hampered by various false starts, delays, and interruptions, and then it abruptly ended in 2009 with the onset of Alzheimer’s disease, six years before his recent death. But his legacy is immense.

His career can easily be divided into two parts, although it’s not so easy to pinpoint a precise dividing line between them. And for those who knew him well or even casually, as I did, it’s hard to prefer the first portion to the second without feeling somewhat guilty.

Common to both parts is a preoccupation with mise-en-scène and the mysterious aspects of collective work, offset by the more solitary and dictatorial tasks of plotting and editing. Rivette’s own collective work was frequently enhanced by improvisation—with actors, with onscreen or offscreen musicians, or with dialogue written just prior to shooting (either by actors or screenwriters)—while the more solitary work of plotting and editing emulated the Godardian paradigm of converting chance into destiny. Read more

The following interview with Alessandro Stellino appeared, in Italian, in filmidee #15, along with Italian translations of three of my essays –- “Entertainment as Oppression,” “In Defense of Non-Masterpieces,” and “Work and Play in the House of Fiction”. What follows is an imperfect and approximate version of this interview in its original English — respecting the structure of the Italian version, although in a few cases reconstructing my answers when I managed to lose the original emails. The interview was conducted over many emails, and I brought it to a close when I declined to reply to the question, “If you could teach a course on film history with the most possible freedom in rewriting the canon, how would your program be?”, which effectively would have obliged me to create an entire syllabus. -– J.R.

In the introduction to Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia, a book that has been particularly relevant for the founding of our magazine, you state: “It’s a strange paradox that about half of my friends and colleagues think that we’re currently approaching the end of cinema as an art form and the end of film criticism as a serious activity, while the other half believe that we’re enjoying some form of exciting resurgence and renaissance in both areas”. Read more

A surprising consequence of my posting “My 25 Favorite Films of the 2000s (so far)” on this site on June 21 was that visits to my site suddenly quadrupled, going from about a thousand per day to well over 4,000. This was encouraging — and for me a good response to Robert Koehler’s charge that such list-making was pointless (because the need for viewing suggestions in a context where there are too many choices strikes me — and apparently many others — as self-evident).

Yet the haste with which I put together my original list also led to some subsequent second thoughts and demurrals. So with this in mind, I’ve come up with a new list of 50 instead of 25, substituting one title in the original list after my friend Janet Bergstrom persuaded me that Chantal Akerman’s From the Other Side was a much worthier example of Akerman’s work than Down There (which I’d listed partially as a provocation, without a sufficient amount of reflection). As with my original list of titles, I’ve stuck to the same rule of including only one film by each filmmaker, and the order is alphabetical. And again, with very few exceptions (e.g., Read more

The following is taken from my “Cannes Journal” in the September-October 1973 issue of Film Comment and corrected in a few particulars in April 2016, after seeing the restored 128-minute director’s cut on a wonderful new Blu-Ray from Olive Films. — J.R.

In theory, the Marché du Film is merely one division of the festival out of many (official selections, Directors’ Fortnight, Critics’ Week, etc.); in practice, every film and every person attending is on the marketplace, to purchase or to be purchased, and all the rest is journalistic euphemism. It was there, at any rate, that I came across Samuel Fuller’s latest film.

Not all of DEAD PIGEON ON BEETHOVEN STREET is peaches and cream, but the beginning is extraordinary — a brilliant burst of action that illustrates the title in lightning flashes — and the mad finale in a weapons room is not far behind. Fuller’s habitual obeisance to the title composer reaches an apogee of sorts in a scene set in the Beethoven Museum, where the head of one of the leads (Glenn Corbett) is cut off by the top of the frame in order to give one of the Master’s pianos a privileged place in the composition. Read more

Written for the Pesaro International Film Festival (July 2016). Most of this piece is made up of earlier articles on the same general subject, so the reader should bear in mind that some of my positions and opinions (such as my estimation of Godard’s Histoire(s) du cinéma) have changed over the years. — J.R.

Criticism on Film

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1990/91):

It’s no secret that serious film criticism in print has become an increasingly scarce commodity, while ‘entertainment news’, bite-size reviewing and other forms of promotion in the media have been steadily expanding. (I’m not including academic film criticism, a burgeoning if relatively sealed-off field which has developed a rhetoric and tradition of its own — the principal focus of David Bordwell’s fascinating book Making Meaning). But the existence of serious film commentary on film, while seldom discussed as an autonomous entity, has been steadily growing, and in some cases supplanting the sort of work which used to appear only in print.

I am not thinking of the countless talking-head ‘documentaries’ about current features — actually extended promos financed by the studios or production companies — which include even such a relatively distinguished example as Chris Marker’s AK (1985), about the making of Kurosawa’s Ran. Read more

1. Are Tarkovsky’s movies still new (by “NEW” I mean do you find new things in recent viewing of the films or surprised by them)? Can viewers/filmmakers still learn from them?

I find that all of Tarkovsky’s films remain new and full of surprises for me. They don’t “date” at all.

2. Should we look at Tarkovsky movies as spiritual movies, religious movies or modern films?

I would say that they’re both spiritual and modern. If they’re also religious, I can’t easily identify them as such.

3. Who/what influenced Tarkovsky’s cinema and which contemporary filmmakers are influenced deeply by his cinema?

Tarkovsky’s cinema, by his own account, was influenced by his father’s poetry, and most likely by other Russian poetry as well. I haven’t reread his book Sculpting in Time recently, but I recall that he had a great deal of reverence for Dovzhenko and Bergman, among others; I don’t know whether or how much they may have influenced him directly.

As for the influence of Tarkovsky on other filmmakers, I could cite Béla Tarr and, more recently, Alex Garland in his film Ex Machina, which is clearly indebted to Solaris. There are undoubtedly many others, but these are the first names that spring to mind. Read more

Written for the Criterion dual format (Blu-ray & DVD) edition of The Young Girls of Rochefort, released in a box set, “The Essential Jacques Demy,” in July 2014. This essay is also posted on Criterion’s web site. — J.R.

Braque, Picasso, Klee, Miro, Matisse . . . C’est ça, la vie.

— Maxence in The Young Girls of Rochefort

Life is disappointing, isn’t it?

— Kyoko in Yasujiro Ozu’s Tokyo Story

Broadly speaking, Jacques Demy’s The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967) is loved in France but tends to be an acquired taste elsewhere. From a stateside perspective, its launch in the U.S. in April 1968 was relatively inauspicious and uncertain. In the New York Times, Renata Adler began her two-paragraph notice by saying, “The Young Girls of Rochefort, a musical that opened at the Cinema Rendezvous, is another of those strange, offbeat movies produced by Mag Bodard in which a conventional, gay form is structured over what would be, in its terms, a catastrophe.” (The three other Bodard films she had in mind were Agnès Varda’s Le bonheur, Michel Deville’s Benjamin, and Demy’s previous film, The Umbrellas of Cherbourg. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (February 24, 2006). I was shocked and upset to learn that Michael Glawogger, the visionary Austrian filmmaker and world traveler, died from malaria in Liberia at age 54. The film of his that left the most lasting impression on me was the remarkable Megacities (1998, see first still below), which filmed people living on the edge in Mumbai, New York City, Moscow, and Mexico City — the first part of an epic documentary trilogy that was followed by Workingman’s Death (2004) and Whores’ Glory (2011, see second still below). I’m sorry to say that this capsule review below is the only time I had occasion to write about his work. — J.R.

In Megacities (1998), Austrian filmmaker Michael Glawogger emulated the city symphony films of the 1920s, and for this 2005 documentary about manual labor around the world he also references film history with clips from Dziga Vertov’s Enthusiasm and Georges Franju’s Blood of the Beasts during the opening credits. Glawogger shoots coal miners in the Ukraine and sulfur miners working a volcanic crater in Java, the slaughter and rendering of goats and bulls in Nigeria, and the dismantling of tankers in Pakistan, emphasizing the workers’ small talk along with their physical activities. Read more

DVD AWARDS 2014

XI edition

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli [absent from photo], Alexander Horwath, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti and Jonathan Rosenbaum, chaired by Peter von Bagh

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON BLU-RAY:

LATE MIZOGUCHI – EIGHT FILMS, 1951-1956 (Kenji Mizoguchi, Japan) – Eureka Entertainment

The publication of eight indisputable masterpieces in stellar transfers on Blu-Ray is a cause for celebration. If Eureka is not exclusive in offering these individual titles, what makes this collection especially praiseworthy and indispensable is the scholarship, imagination and care that went into the accompanying 344-page booklet. Over 60 rare production stills are included, many featuring Mizoguchi at work. Striking essays by Keiko I. McDonald, Mark Le Fanu, and Nakagawa Masako are anthologized along with extensively annotated translations of some of the key sources of Japanese literature that inspired some of Mizoguchi’s late films. The volume closes with tributes to the great director written by Tarkovsky, Rivette, Godard, Straub, Angelopoulos, Shinoda, and others. Tony Rayns provides spoken essays and some full-length commentaries.

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON DVD:

PINTILIE, CINEAST (Lucian Pintilie, Romania) – Transilvania Films

An impeccable collection devoted to eleven films by an important and neglected maverick Romanian filmmaker, masterful and acerbic, with invaluable contextualizing extras concerning his life, work, and career drawn from ten separate sources. Read more

A column for the Spanish magazine Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. I believe it was written circa May 2014-. J.R.

En movimiento: Welles in Woodstock

Jonathan Rosenbaum

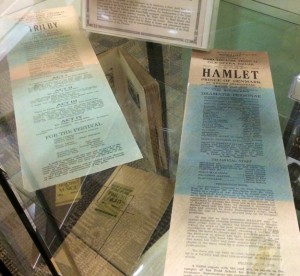

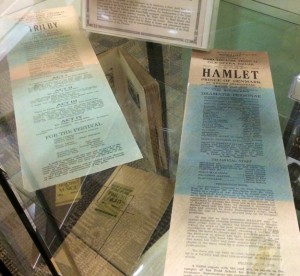

I’ve recently returned from Woodstock Celebrates Orson Welles, a delightful two-day event in Illinois (16-17 May) organized by Kathleen Spaltro and commemorating the 80th anniversary of the Todd Theatre Festival held at the Woodstock Opera House in 1934, orchestrated by Welles at the age of 19 and sponsored by his mentor and one of his lifelong best friends, Roger Hill — headmaster of the Todd School for Boys, which Welles attended from 1926 to 1930.

When Welles graduated from Todd, Hill wanted him to attend Harvard while Welles’ guardian, Dr. Maurice Bernstein (whom Everett Sloane’s character in Citizen Kane was named after), hoped he would go to Cornell. But Welles, still under the spell of an article published by one of Chicago’s leading drama critics, Ashton Stevens (who wrote for the Chicago Herald-American, a Hearst newspaper, and was the model for Jed Leland in Kane), predicting that the young genius was destined to become a major actor, didn’t want to go to college. So a compromise was struck: Welles would travel to Scotland, Ireland, and England on a sketching tour before embarking on any formal education, writing letters home to chart his progress and his adventures. Read more

The great Hungarian filmmaker Jancsó Miklós (or Miklós Jancsó, as he is known in the West) died peacefully in his sleep on January 31, 2014. Mehelli Modi, who has released excellent DVD editions of some of his films on Second Run in the U.K. (and has more recently brought out a Blu-Ray of his remarkable 1974 Electra, My Love), emailed me a couple of weeks later, asking, on behalf of Jancsó’s sons Nyika and David, if I could write something to be read at his memorial service on February 22. Here is what I sent back. — J.R.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to say that I regard Jancsó Miklós as one of the great lost continents of world cinema, especially outside Hungary — and largely, I suspect, because Hungarian history, which forms a major part of his oeuvre, is another lost continent from the vantage point of the West. With the possible exception of Sergei Eisenstein, I suspect that Jancsó remains the supreme example of a film artist who views history as a multilayered and passionate form of pageantry, something to be sung and danced, by the camera as well as by the actors, and, speaking more figuratively, by the audience. Read more

From the Summer 2018 issue of Cinema Scope. — J.R.

1. Second Thoughts First

In the introduction to my forthcoming collection Cinematic Encounters: Interviews and Dialogues, I make the argument that although Truffaut’s book-length interview with Hitchcock doesn’t qualify precisely as film criticism, it nonetheless had a decisive critical effect on film taste. By the same token, on Criterion’s very welcome Blu-ray edition of Frank Borzage’s Moonrise (1958), Peter Cowie’s interview with Borzage critic/biographer Hervé Dumont — whose book on the director should be shelved and considered alongside Chris Fujiwara’s book for the same publisher (McFarland) on Jacques Tourneur — primed me perfectly for my second look at this masterpiece, and made it register far more powerfully this time. It certainly performs this task better than Philip Kemp’s accompanying essay, which, in spite of much useful information, falters in its insistence on framing Moonrise through the lens of film noir, and even more when, while rightly praising the character of Rex Ingram’s Mose, the author remarks that “It would be hard to think of another American film of the period where a black man acts as adviser and mentor to a white Southerner.” It’s not so hard, really, if one thinks of Clarence Brown’s Intruder in the Dust (1949) and/or Tourneur’s Stars in My Crown (1950); and it’s even quite easy if, following Dumont’s lead on Moonrise, one regards the Tourneur masterpiece neither as a noir (a lazy escape hatch) nor as a western (as Jacques Lourcelles does), but as a discreet form of German Expressionism, implicitly favouring thoughtful philosophy and metaphysics over simple gloom and doom. Read more

It’s a genuine pity that this remarkable new book — a kind of summation and extension of Adrian Martin’s work in film analysis and the history of film criticism in Australia, France, Spain, the U.K., and the U.S. over the past two decades — is commercially available only at the whopping price of $80.75 on Amazon — or $76, if you’re willing to settle for a Kindle edition. As a longtime friend, colleague, and collaborator of Martin’s, I was fortunate enough to receive a free inscribed copy, but most of the rest of you will have to either shell out a fortune or wait for a softcover edition. All I can do now, really, having received this book only yesterday, is signal just a few of its many riches. Girish Shambu, Adrian’s irreplaceable coeditor at LOLA, has already posted a helpful summary of the book’s “four [interests] that animate the work” on his web site, so the most I can hope to do here is cite just a few treasured and brilliant passages that already have either sent me back to the films and texts being discussed or extended my current (re)reading and (re)viewing lists:

G. Cabrera Infante writing in 1957 about Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), pp, 6-7. Read more

G. Cabrera Infante writing in 1957 about Tea and Sympathy (Vincente Minnelli, 1956), pp, 6-7. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, June 1, 2002; slightly tweaked in 2014. — J.R.

One reason Paul Schrader’s Calvinist obsessions have become tiresome — even when someone else is partially responsible for the writing, as is the case here — is that he seems more invested in their perpetuation and exploitation than in their exploration. Yet I have to concede that he’s become an unusually skillful and sensitive director of actors, and the inventive performances — Greg Kinnear as Bob Crane (the wholesome star of Hogan’s Heroes who became a sex addict) and Willem Dafoe as his seedy sidekick and fellow pornographer — keep this story interesting in spite of its puritanical framework. Watchable, but not very insightful (2002, 107 min.). Written by Michael Gerbosi; with Rita Wilson and Maria Bello. (JR)

Read more

Read more

Log Out

If I’d had my druthers, I would have seen Jacques Rivette’s masterpiece Out 1 for the third time this past weekend, at the Gene Siskel Film Center. It’s still one of my all-time favorites, offering far more pleasure, enlightenment, and sheer stimulation over its dozen and a half hours than any dozen routine commercial releases (which would cumulatively last twice as long, and most of which I wouldn’t dream of seeing if my job didn’t require it). Thanks to work, I had to content myself with about three of the eight episodes, #3, #7, and #8. Still, it was gratifying to see this much of it with such an appreciative and good-sized audience (about 140) who laughed in all the right places and seemed to enjoy it as much as I did. (The experience was enhanced by a superb job of “soft subtitling” supervised by Sally Shafto, director of the last Big Muddy Film Festival.)

I realize this is the third post about Rivette in the past couple weeks (see Pat Graham’s Celine & Julie: The Typeface and One Sings, the Other Doesn’t), but he’s the kind of filmmaker who fosters obsessiveness of various kinds.

Read more