This appeared in Omni, circa December 1980, and, if memory serves, a version of it also turned up in my book Film: The Front Line 1983. For about a year (1977-78), Hock and I (and also Raymond Durgnat, for a spell) , all colleagues at the Department of Visual Arts at the University of California, San Diego, shared a beautiful house in a Del Mar canyon that we sublet from an anthropology professor there who was away on a sabbatical. — J.R.

A single thread of 16mm film runs through three side-by-side projectors, all aimed at the same wall. Twenty-two and a half second elapse between the time when the first and the second screen images appear and the same amount of time passes between the appearance of the same silent image in the second and third, so that every image can be expected to occur twice in each 45-second cycle.

The title of this 70-minute film piece, made last year, is Southern California. Described by its maker, Louis Hock, as a “triptych cinemural,” it is also identified by him with precise measurements, like a temporal painting: 30 feet X 7.5 feet X70 minutes. And temporal painting may not be a farfetched description for what this thirty-two-year-old filmmaker — a man preoccupied with time and motion — is interested in exploring.

One curious consequence of the method of Southern California is a novel kind of film rhythm that is at once suspenseful and restful — and oddly evocative of the movement of waves — every time an image ripples across the three projected frames. It also creates a certain analytical distance between the spectator and the cinemural as three temporal stages in the same film sequence are viewed simultaneously.

Why does Hock call it Southern California? Because it is mainly an anthology of the sort of things that any tourist to that fabulous region might see: the unrecognizable, anonymous skyscrapers of downtown Los Angeles, as seen from the rotating Angel’s Flight Bar, high atop the Hyatt-Regency Hotel; a multicolored flower farm on a hillside close to San Clemente; a bight array of fruits and vegetables at a high-priced supermarket in La Jolla.

There’s even a fair stretch of late-night television, including part of a Rory Calhoun Western and a used-car ad featuring Cal Worthington and His Dog Spot, which is especially familiar to denizens of southern California. Each image, without exception, appears simultaneously in the same “before, during and after” format. And thanks to the placidity and crispness of Hock’s compositions, this format winds up giving all these diverse icons a strange sort of epic grandeur.

Although he is a native Californian, Hock grew up in Tucson. He attended the School of the Art Institute in Chicago before returning to his home state in 1977, to teach filmmaking in San Diego. He has plenty to say about the place today. “The whole sea of television there has the movies, the aerospace industry, the cars, the health-food industry, the Dodgers, and the grizzly bear,” he remarked recently on one of his East Coast visits. “I wanted to suggest in the film how all of California’s industry uses us like an advertisement for itself on television.”

When he can, Hock prefers to show Southern California outdoors. “It’s not made for an audience that’s subdued — which comes about by putting them in a dark room and having them sit through it,” he said earlier this year. “It’s made for a casual audience. I intend to show it in large showroom windows on the street, or on a blank wall on the side of a building, or on a billboard or a semitruck — in a public place. You can walk into it at any point.”

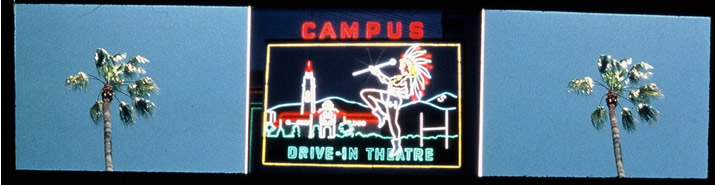

More recently Hock has been able to realize this dream, showing Southern California in several outdoor California locations. In a parking lot adjacent to the Santa Monica Pier, a punk-rock band called the Armaghetto Ensemble pulled up in a flatbed truck and offered free accompaniment. The film was projected on a screen 8 feet high and 30 feet across.

At the Los Angeles Institute for Contemporary Art, the movie was projected into a semitractor-trailer; at the San Francisco Art Institute, Hock rear-projected it onto windows, and on the University of California, San Diego campus, he used the outside of Mandeville Auditorium. Since this successful tour, Hock has been planning a half-hour black-and-white sequel.

And there are other California movies: One, Pacific Time, the quirkiest of Hock’s films, slows time down to such a crawl that subtitles have to be provided — in Greek, of course — as pundits David Antin and Allan Kaprow, waiting endlessly at a bus stop in downtown San Diego, recite a Platonic dialogue in English> But most of Hock’s films examine the structure of certain processes by speeding time up.

The quasi-scientific, “documentary” nature of his films — the degree to which they literally document things — has been noted by several reviewers. One of them, Mitch Tuchman, says that Hock’s Studies in Chronovision “gauges nature’s clocks by one of man’s,” adding, parenthetically, that “the motion picture camera measures time, too, twenty-four frames per second.”

Hock recalls that when he was setting up his camera on the fiftieth floor of Sears Tower for Picture Window, he was a bit unnerved to find three men in gray suits standing directly behind him: “They looked real serious, as if they were going to throw me off the building. It turned out that they were trying to figure out how much the building swayed in a strong wind and were hoping they could use the camera to find out.”

The Mirror and the Window (1978), another triple-screen work, takes the unusual approach of creating a kinetic close-up portrait of Hock n Del Mar, California — produced by filming his own face a frame at a time, every morning and evening over a ten-month period.

“I was always curious, you know, about the vanity that prevails in the morning when you look in the mirror,” Hock says wryly, “and in the evening, when you say, `My God, I’m fat,’ or, `I’m skinny,’ or, `I’m ugly,’ or, `I look healthy,’ or, `I look tired.’ I always thought that you could chalk this up to vanity, that men’s faces are pretty stable.

“But, as it turns out, there’s an immense plasticity that the face goes through. It’s like some kinf of modeling clay contorting around. The neck is a twisting snake, the jaws raise and lower like drawbridges, and the eyes turn around in their sockets and squint.” It takes only six or seven minutes for this ten-month process to be viewed.

Like his own films, Hock is strongly environmental — often reflecting whatever terrain he happens to be passing through. “People keep going to theaters and seeing movies about things that are far away. The films themselves are distant, like games. And I get tired of showing my films in small rooms to the same audiences, the sort of circuit that an independent filmmaker does: show and tell, with a straw hat and a cane, around the country.

“That’s why I like to show Southern California in outdoor environments,” Hock adds, becoming eager again, “so that people have access to it.” As an exhibitor of his own films, he is already “scouting” diverse locations for this project, from New York to Santa Fe to Berkeley, in the course of his travels, hoping to find places where his experiments with time can become natural parts of the scenery.