From Film Comment (September-October 1998). This is a restructured and substantially revised, updated, and otherwise altered version of my “Trailer for Histoire(s) du cinéma,” which appeared originally in French in the Spring 1997 issue of Trafic. Among the more important changes are a suppression of virtually all of my multiple comparisons of Histoire(s) du cinéma with Finnegans Wake in the original (which, paradoxically, seemed more appropriate in a French publication than in an American one), an expansion of much of the interview material, and an extended quotation from Godard’s review of Rob Tregenza’s Talking to Strangers.

My apologies for some format irregularities that I wasn’t able to fix. -– J.R.

GODARD AS CRITIC

JLG (at press conference): I still look at movies the same way today than I did [at the time of the New Wave], but I know it’s not the same world, exactly. Even if we enter the theater the same way, we don’t go out the same way.

Q: How is it different?

JLG: Less hope.…Paris is the only city in the world where you can still see all the film production that’s interesting, especially independent movies, and if you don’t live there, you’re far away from the production. Near Geneva, where I spend most of my time, you have only American pictures. And since I don’t even live in the city, for me it’s 60 kilometers each way. So maybe you can go 60 kilometers to see Demi Moore, but to go that far again on the way back is too much!…When I went to see Striptease, there was no beginning, no middle, and no end. So I always wonder why people say a story has to be that way, especially to me.

Apart from Luc Moullet, who still publishes criticism regularly, and Olivier Assayas, who continues to publish more sporadically, Godard is arguably the only critic-turned-filmmaker from Cahiers du cinéma who has never abandoned his first vocation. This is a question of attitude as much as practice — the fact that Godard has never swerved from his initial claim at the start of his career that criticism and filmmaking were for him two versions of the same activity. (Although Truffaut continued to write about films and filmmakers after becoming a director, he took an increasingly dim view of criticism prior to his death that came close to repudiating his original work as a critic — virtually equating criticism with everyday reviewing and journalism, “good” and “bad” press, in “What Do Critics Dream About?”, his 1975 introduction to The Films of My Life. It’s impossible to imagine Godard ever writing, “No artist ever accepts the critic’s role on a profound level” -– a characteristic utterance in that essay.)

As one indication of how closely Godard has adhered to this brief, consider his short essay “Reality as the Bride of Fiction,” a review of Rob Tregenza’s 1987 Talking to Strangers written for the 1996 Toronto Film Festival catalog. Unlike the other participants in the “Dialogues: Talking with Pictures” series, Godard wasn’t content simply to endorse his selection; he insisted on taking it apart critically. “If the Cahiers still existed,” he began, “and I did too, this is what I’d say about Rob Tregenza’s first film, composed, we all know, of nine one-shot sequences”.

He then proceeded to label four of these sequences “remarkable and at times astonishing,” one of them “rather interesting,” and the remaining four unsuccessful recalling along the way that he once praised Jacques Becker’s Montpartnasse 19 precisely for its failure — and then, before going into specifics and various asides (“Oh, my Jane Campion, why did you let them drop the piano on you?”), adding a patch of metaphorical theory to account for his biases that arguably can also be read in part as a kind of gloss on his 1975 feature Numéro deux:

“Because here reality walks hand-in-hand with fiction. The great Lévi-Strauss would say: the elementary structures of kinship between fiction and reality’ And I would add that fiction, the slut, trips up reality as soon as reality wants to possess her. Theirs is not a heterosexual marriage. Reality and fiction are man and woman at the same time, and each reproaches the other for being what she or he is, not for being what she or he is not. And this film could only be made in America, which — as we have known since Giraudoux — sees an enemy in only that which resembles it — in its failings.”

***

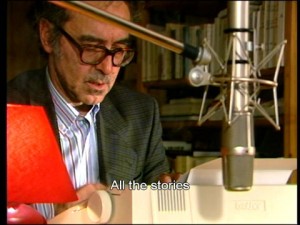

Dominating the first four chapters (1a, 1b, 2a, 2b) are the alternating sounds of typing and of film turning on an editing table: staccato and legato, the sounds of Godard’s two activities as a critic. (The style becomes exclusively — and beautifully — legato in 3a, on Italian neorealism, the most moving episode to date.) The continuity between writing and filming is apparent in many respects here, above all in the important role played by The Wrong Man (1956)—the subject of the longest, most serious, and most detailed critique written by Godard for Cahiers du cinéma — in episode 4a, devoted to Hitchcock, which shows Godard coming full circle back to the preoccupations of his writing forty years ago.

JLG: I put in Hitchcock because during a certain epoch, for five years, in my opinion, he really was the master of the universe. More than Hitler, more than Napoleon. He had a control of the public that one else had. JR: What about Ronald Reagan? Didn’t he have the same control?

JLG: No, because Hitchcock was a poet. And Hitchcock was a poet on a universal level, not like Rilke. He was the only poet maudit to have a huge success. Rilke wasn’t one, Rimbaud wasn’t. He was a poet maudit for everyone; Notorious wasn’t like James Joyce. I remember André Bazin was very angry with us. And something which is very astonishing with Hitchcock is that you don’t remember what the story of Notorious is, or why Janet Leigh is going to the Bates Motel. You remember one pair of spectacles or a windmill — that’s what millions and millions of people remember. If you remember Notorious, what do you remember? Wine bottles. You don’t remember Ingrid Bergman. When you remember Griffith or Welles or Eisenstein or me, you don’t remember ordinary objects. He is the only one.

JR: Just as with neorealism, as you show, you remember only people. JLG: Yes, it’s the exact contrary. You remember feelings, or the death of Anna Magnani. It’s very clear.

JR: It was a very important moment for me in 4a when you included almost an entire sequence from The Wrong Man, of Henry Fonda alone in his jail cell, because that linked your video with one of your major critical pieces for the Cahiers. By contrast, I don’t recall you including any clips from Bitter Victory or A Time to Love and a Time to Die.

JR: It was a very important moment for me in 4a when you included almost an entire sequence from The Wrong Man, of Henry Fonda alone in his jail cell, because that linked your video with one of your major critical pieces for the Cahiers. By contrast, I don’t recall you including any clips from Bitter Victory or A Time to Love and a Time to Die.

JLG: No.

JR: And it’s interesting that you call Hitchcock the only filmmaker apart from Dreyer who could film miracles, because some people have argued that the miracle in The Wrong Man isn’t believable.

JLG: But it was based on a true story! And Ordet and The Wrong Man were both commercial flops; that’s another connection.

JR: It surprised me yesterday when you said that Hélas pour moi was more commercially successful in the U.S. because it’s one of your most difficult films.

JLG: Yes, and it’s not very successful. It’s very far away from what I had in mind. It was supposed to be an everyday picture, a Wednesday or a Thursday picture, and in the end, because of [Gérard] Depardieu, it became a Sunday picture, in Sunday clothes. He changed everything. It was maybe the beginning of For Ever Mozart. I wanted to have a lot of characters together, paying attention to each of them, even the small ones. We could have shot the people beside Depardieu and it would have been the same movie. I started too soon on that picture, which was a disaster. I asked the producer on that to delay it for one year, and he didn’t want me to. I wasn’t ready. I didn’t know exactly what I wanted to do. I just had the story, and it was too soon to deliver it. I know it needed more reflection.

***

Insofar as Godard, like Rivette, has remained a film critic throughout most of hiscareer as a filmmaker, it is important to clarify how their methods of quotation, paraphrase, and allusion, unlike those of practically every other filmmaker, generally remain critical. When Allen, DePalma, Scorsese, and Tarantino echo shots or sequences from other filmmakers, the gesture is always one of postmodernist appropriation, not one of critical transformation, and the same thing can be said about the hommages of (among others) Truffaut and Bertolucci. (For me, the only time when Truffaut as a filmmaker continues to function as a critic is in the powerful act of self-criticism implied in The Green Room [1978] regarding the morbidity and rigidity of la politique des auteurs as a personal system.)

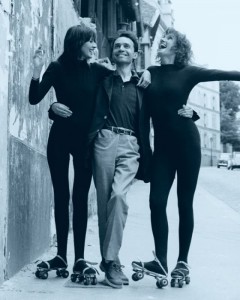

When Rivette literally quotes the Tower of Babel sequence from Metropolis in Paris Belongs to Us, thereby criticizing the metaphysical presuppositions of his characters, or when Resnais virtually duplicates a sequence of shots from Gilda inside Delphine Seyrig’s room in Last Year at Marienbad, thereby locating the romantic mystifications of Robbe-Grillet within the even larger romantic mystifications of Hollywood, a certain kind of critical commentary is taking place, even if it’s only implied in the second instance. The same process is at work on a much more elaborate scale in Celine and Julie Go Boating, when Rivette takes the critical discoveries of doubling in Hitchcock, made by Truffaut in relation to Shadow of a Doubt (“Skeleton Keys” — a major piece from 1954 inexplicably omitted in both volumes of Truffaut’s criticism in English, but available in Film Culture no. 32, Spring 1964, and Cahiers du Cinema in English no. 2, 1966) and by Godard in relation to The Wrong Man (translated without its original title, “The Cinema and its Double,” in Godard on Godard, New York: Da Capo, 1986, 48-55), and then applies these principles to the same evolving “double” structure of his own film, doubling shots as well as scenes. But the same thing obviously can’t be said for Allen and DePalma appropriating the baby carriage from Potemkin in Bananas and The Untouchables, for Schrader and Scorsese using part of the plot of The Searchers in Taxi Driver, for DePalma borrowing a 360-degree dolly around a kissing couple (along with Bernard Herrmann) from Vertigo to use in Obsession, for Tarantino getting Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction to imitate Anna Karina’s dance around a pool table in Vivre sa vie, or, for that matter, Rivette dressing Juliet Berto and Dominique Labourier in black tights à la Musidora when they steal a book from a library in Celine and Julie Go Boating.

For Godard, the functions of critique and hommage sometimes overlap: in JLG/JLG and in 2 x 50 ans de cinéma français, it is the latter that predominates, even if the deliberate obscurity of certain references in 2 x 50 ans arguably corresponds in certain cases to a particular critical position. (Characteristically, the touching hommage to Roger Leenhardt in the latter — included not in the Diderot to Daney “pantheon” of writers at the end but much earlier, in what is probably the longest clip in the video — is an unattributed extract from Godard’s own The Married Woman.) There is nothing critical about the groupings of stills and portraits in chapter 1a organized around Eisenstein, Welles, Renoir, and Vigo. But an hommage becomes a critique when it defamiliarizes the material, as the Russian formalists might say — which is why the clips in Histoire(s) that tend to be the most mysterious are usually the ones that one recognizes: James Gleason drunkenly rocking back and forth in a rocking chair in The Night of the Hunter (in chapter 3a — an image recalling Lillian Gish in Intolerance, reminding one of how closely Laughton studied Griffith), the screen test on board a ship in King Kong (recycled repeatedly throughout the series). And when Godard wants to cite a particular director within a given context, his choices are sometimes anything but obvious. In 3a, which details some of the sources of the New Wave (“It’s all over the place,” I recall Godard saying to me in Toronto, “because the New Wave was all over the place”), the major reference to Robert Aldrich is a pair of female wrestlers at work in …All the Marbles, and the major reference to Preston Sturges is by way of The Beautiful Blonde from Bashful Bend….

JR: Have there been many cases where you can’t acquire the clips you want?

JLG: If I don’t have it, I take another one, and then I tell another story, more or less, with no problem. In the last episode [4b], any shots can be good. I need documentary shots that are both strong and of no importance. JR: What are for you the main differences between the early episodes and the late ones?

JLG: The early episodes are more linked to cinematography; the last ones are more about the philosophy of what cinema is in this century, more about what is specific to cinema… For me, the reason why I was not so commercial was that it wasn’t very clear to me whether I was writing a novel or writing an essay. I like both of them, but now, in Histoire(s) du cinéma, I’m sure it’s an essay. It’s easier for me and it’s better that way.

JR: It seems to me that a different kind of energy goes into your films and your videos. It’s clear, for instance, that Histoire(s) du cinema couldn’t be a film. Why is this the case?

JLG: Well, I’d say for technical reasons, because video is closer to painting or to music. You work with your hands like a musician with an instrument, and you play it. In moviemaking, you can’t say that the camera is an instrument you play through; it’s something different. And then there’s the possibility of superimposition, which isn’t the same in movies, where it has to go through different technical processes. The image isn’t good enough in video, but it’s easier. You only have two images to work with in video; it’s like having only two motives in music, and the possibilities of creating a relationship between two images are infinite. The big difference is that if you shoot the three stone lions of Eisenstein in video, it can be an entire Warhol movie.

CODA: HISTOIRE(S) DU CINÉMA AS LEGAL AND POLITICAL PRECEDENT

JR: There’s an important legal precedent in the way Histoire(s) du cinéma uses clips. There are some other very interesting recent videos that use clips critically — Mark Rappaport’s Rock Hudson’s Home Movies and From the Journals of Jean Seberg and Thom Andersen and Noël Burch’s Red Hollywood –– without acquiring rights. It’s usually impossible to get rights for the clips in works of this kind, so they’ve all been made outside the system.

JLG: Gaumont, which owns Histoire(s) du cinéma, probably has a big worry now, because if it’s me it’s one thing, but if it’s Gaumont…The first two episodes were shown on five separate European TV channels, so it is a precedent, because if it wasn’t me with the friendship of Gaumont, no other producer would have done it due to the rights problem. But for me there’s a difference between an extract and a quotation. If it’s an extract, you have to pay, because you’re taking advantage of something you have not done and you are more or less making business out of it. If it’s a quotation — and it’s more evident in my work that it’s a quotation — then you don’t have to pay. But it’s not legally admitted in pictures.

JR: Yes, but it also isn’t legally acknowledged that films and videos can be criticism.

JLG: It’s the only thing video can be — and should be.

One could argue that the decline of film criticism in recent years — observable in the habits of most newspaper and magazine editors in both Europe and North America as well as most films academics in North America — is not so much a reflection of the changing tastes of audiences (as these editors and academics often insist) as it is the power of multicorporations to eliminate everything that interferes with their promotion. Just as the so-called “American independent” filmmakers promoted by the Hollywood studios via Sundance usually means the filmmakers who have lost their independence, “film criticism” in the mainstream now refers mainly to promotional journalism; true independents and critics have to function in the margins. On more ways than one, the traffic is moving underground. [JLG in his press conference: To me, culture is business. Art is something different. Music is not culture, but selling music is.]

Philosophically speaking, Histoire(s) du cinéma is a dangerous work because it dares to raise the issue of whom cinema, film criticism, and film history belong to. Truthfully, they belong to everyone today with a VCR, but contractually, they belong to the state, and the state today — especially from the standpoint of an American like myself — is Disney. It is Disney and its client states such as Miramax that set our cultural agendas and rewrite our official film histories and critiques via the mass media. (It is Miramax that determines that The Wings of the Dove is at least a hundred times more important than the color version of Jacques Tati’s Jour de fête, which it also controls; the mass media merely chime in with their assent.) By writing his own film history and criticism on video, using means that are readily available and relatively inexpensive, Godard is proposing a direction that filmmakers and video artists everywhere could explore with benefit — the direction of appropriation, a movement already inaugurated by the critical and historical reappraisals of the New Wave, and continued in Histoire(s) du cinéma by other and more subterranean means, such as poetry and autobiography. Recalling the title of Rivette’s first feature, I propose a slogan: Paramount belongs to us.