In most respects, I’m delighted and honored that a version of the following essay was published in Issue Two of the journal Music & Literature, which is devoted to László Krasznahorkai, Béla Tarr, and Max Neumann, In fact, this essay was commissioned by the editors of this handsome special issue, and my only reason for posting my original version is that a few stylistic edits were made, in what I’m sure were sincere efforts to clarify some of the entanglements in my lengthy sentences, that unfortunately yielded some embarrassing factual errors in the piece, as well as a few significant cuts. (It now appears that I read portions of the French translation of Krasznahorkai’s novel before I ever saw Tarr’s film and that Erich Auerbach’s great book Mimesis now includes an analysis of Light in August that no one has previously read; and the remarkable observation from Dan Gunn that I quoted has been deleted.) So, just to keep the record straight, here, for better and for worse, is exactly what I wrote. More recently, in mid-January 2015, I belatedly received a copy of this article with the above Introduction reprinted in Scalarama, a publication put together by Stanley Schtinter to accompany a tour of Sátántangó in the U.K. in September 2014. -– J.R.

Part of the greatness of Béla Tarr’s radical film adaptation of László Krasznahorkai’s first novel, Sátántangó, is a curious combination of faithfulness and what might be described as the theoretical limits of any possible faithfulness in the “translation” of prose into sounds and images. There’s something undeniably startling as well as radical about converting a novel that’s only 274 pages long (in its graceful English translation by George Szirtes) into a film that lasts 450 minutes, but the relation between the long sentences of the former and the long takes of the latter is central to that conversion. The experience of following a sentence may not necessarily be identical to the experience of following one or more characters, whether this is on a page or on a screen, but the existential aspect of implicating us in the shape and duration of an event while we attend to it, with all the moral and political ramifications this “collaboration” implies, is common to both experiences.

In certain respects, one might argue that the political and social differences between novel and film are far less important than the separate cultural reflexes of Americans and Hungarians following the narrative in either of its phenomenological forms. A Cuban-born friend of mine who fought in Castro’s army before fleeing to the U.S. has told me that the film Sátántangó captures the tragicomedy of Stalinist bureaucracy and surveillance better than anything else he has encountered, in film or in narrative prose, whereas Krasznahorkai and Tarr have both suggested in several interviews, no less plausibly, that nothing could have been further from their minds while composing this narrative in its separate forms. For them, it appears, the essential truth of the story is more metaphysical than sociopolitical, and a post-Christian and/or post-Biblical context is what dominates. (This context is apparent even in the titles of the first two collaborations between Krasznahorkai and Tarr, Damnation and Sátántangó, and both men have acknowledged in interviews that their last film together, the apocalyptic The Turin Horse, is structured around the six days of creation found in Genesis.) But surely the playing out of its metaphysical meanings is contingent on the reader/viewer’s sense of his or her own identity in relation to the story’s blighted, godforsaken, and self-centered characters. Whichever side of the Cold War one happens to be on, or whether one chooses to accept a Cold War context at all, these arguably become the elected meanings more than the projected ones, although it’s important to add that Sátántangó was written and originally published in the mid-1980s, when Hungary was still under Soviet Communist rule, and therefore a period when Communism couldn’t be addressed directly, even if its bureaucratic manifestations are omnipresent and central to the narrative. It would perhaps be unduly facile to insist that the blatant (albeit twisted and perverted) religious context has replaced the suppressed political context in fixing the moral implications of the story, but it seems hard to deny that this relationship exists on some level.

By the same token, William Faulkner’s Light in August, my favorite novel in any language, has almost never been described as a Communist novel. Yet if one reads it as a proletarian American novel of its period (1932), one could argue that it bears many of the characteristic attributes, formal and otherwise, that one might associate with that category as well as that era — for instance, the restless, almost twitching movement of the narrative from one location to the next (which one could also associate with, say, Charlie Chaplin’s Modern Times and John Dos Passos’s The Big Money, both from 1936), reflecting the economic instability of most of the characters.

As someone who grew up in northwestern Alabama and spent the first sixteen years of my life there (1943-1959), I have treasured Light in August, which I first read shortly after I left for a New England boarding school, as the novel that best captures the quasi-totalitarian climate of that culture, especially in relation to race. Even though this is clearly not addressed as directly as Faulkner addresses racism in Light in August, it seems no less clear that Tarr and Krasznahorkai recognize and understand this climate with comparable depth, not to mention sorrow and outrage, and regard it no less metaphysically as a blight on humanity. So, whether it’s willed or not, Sátántangó deserves to be regarded in both its forms as one of the great narratives about Stalinism and its effects on alienating people from themselves as well as each other — including, one should stress, the lingering effects of that Stalinism on a capitalist society.

For many years, Béla Tarr and I have had a running debate about the relation of the film (and, by implication, the novel) Sátántangó to Light in August, which also focuses largely on the simultaneous events of a single day in a depressed, flat rural area as seen through the consciousness of several alienated characters — alienated from themselves as well as from one another — including a fallen patriarch who observes all the others named Reverend Hightower (a name and figure that already anticipates some of the structure and vision of Tarr and Krasznahorkai’s film The Man from London), and who might have served as his community’s conscience if they all hadn’t deteriorated into an apocalyptic, post-ethical (and specifically post-Christian) stupor. Both novels are largely centered around shocking central episodes devoted to atrocious acts that, even more shockingly, are described with a certain amount of lyricism — in Light in August, the pursuit, castration, and murder of the racially ambiguous Joe Christmas by a racist named Percy Grimm who regards him as black; in Sátántangó, the torture and fatal poisoning of a cat by a feeble-minded young girl named Esti who then kills herself with some of the same rat poison.

Other rough parallels of Sátántangó with Faulkner, if not with Light in August per se, include a narrative that shifts between the separate viewpoints of diverse characters (cf. As I Lay Dying), an important section framed around the consciousness of a feeble-minded and innocent character –- Benjy in The Sound and the Fury, Esti in Sátántangó — and a form of black comedy that forms around the meanness, pettiness, and spite of many of the central characters (the members of the failed farm collective in Sátántangó, the Snopes family in Faulkner’s late trilogy — The Hamlet, The Town, and The Mansion –- devoted to their ascendancy).

Béla Tarr doesn’t see any connection between Sátántangó and Light in August, or, more generally, between Krasznahorkai and Faulkner; he has told me more than once that he finds the Hungarian translations of Faulkner so inadequate that he doesn’t feel he knows this American author at all, and it’s worth adding that one could also trace many of Faulkner’s methods back to Joseph Conrad, e.g. the events of one day perceived from the perspective of separate characters, as in Nostromo. (I can also readily acknowledge that the sarcastic wit of Krasznahorkai’s story, which arguably goes even beyond Faulkner’s Snopes trilogy in its sense of absurdist and nihilist farce, seems quintessentially Eastern European, making the apocalyptic pessimism of this novel distinct from both Faulkner and Conrad, even after one factors in the latter’s Polish origins.) But even so, there are certain similarities between long sentences by Faulkner and Krasznahorkai that are worth dwelling upon. Both convey a certain compulsive movement that can be described as a lyrical and rhetorical delirium around scenes and narrative situations that are virtually static, furious maelstroms that swirl around a void: not just the solitary and flabby inertia and impotence of Hightower and Krasznahorkai’s doctor stewing in their own juices (which occasions a certain hilarious Beckett-like comedy in Krasznahorkai’s novel and Tarr’s film, which lingers over the seemingly intense labor and straining effort required for an alcoholic to drink himself into oblivion, but only a kind of pitying despair or self-loathing identification in Faulkner’s), but also the slow-motion progress of a wagon mounting a hill as perceived by Lena Grove in the present-tense opening of Faulkner’s novel, and the relentless way Tarr’s camera follows various characters walking down dusty roads throughout much of Sátántangó.

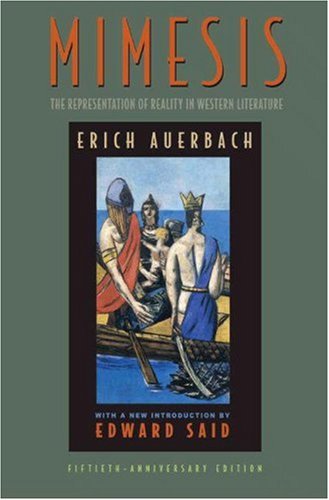

Nevertheless, the philosophical differences between Faulkner and Krasznahorkai are profound. The two major characters of Light in August, who never meet — Lena Grove (a pregnant and single young white woman on the road from Alabama, searching in Mississippi for the father of her child-to-be) and Joe Christmas (a doomed, bitter orphan of thirty-three with alleged biracial origins who can’t ever discover whether he’s white or black) — are presented generally in terms of the respective styles of The Odyssey and the Old Testament, at least as they’re described by Erich Auerbach in ”Odysseus’ Scar,” the brilliant first chapter of his Mimesis: seamless and untroubled in Homer, like figures on Keats’s Grecian urn, and turbulent and full of gaps, like expressionist bolts of lightning, in the story of Abraham. As Claire Denis once suggested to me, Light in August may be the best novel ever written about racism, and it’s also a profoundly troubled moral inquiry about the failure of southern Christianity to cope with racism. It boldly alternates pastoral comedy (Grove) with urban tragedy (Christmas), a cinematic form of stillness, presence, and unchanging persistence (Grove, who opens the novel in the present tense) with a very literary form of tortured narrative progression (Christmas)

Nevertheless, the philosophical differences between Faulkner and Krasznahorkai are profound. The two major characters of Light in August, who never meet — Lena Grove (a pregnant and single young white woman on the road from Alabama, searching in Mississippi for the father of her child-to-be) and Joe Christmas (a doomed, bitter orphan of thirty-three with alleged biracial origins who can’t ever discover whether he’s white or black) — are presented generally in terms of the respective styles of The Odyssey and the Old Testament, at least as they’re described by Erich Auerbach in ”Odysseus’ Scar,” the brilliant first chapter of his Mimesis: seamless and untroubled in Homer, like figures on Keats’s Grecian urn, and turbulent and full of gaps, like expressionist bolts of lightning, in the story of Abraham. As Claire Denis once suggested to me, Light in August may be the best novel ever written about racism, and it’s also a profoundly troubled moral inquiry about the failure of southern Christianity to cope with racism. It boldly alternates pastoral comedy (Grove) with urban tragedy (Christmas), a cinematic form of stillness, presence, and unchanging persistence (Grove, who opens the novel in the present tense) with a very literary form of tortured narrative progression (Christmas)

Here is the way Auerbach summarizes the two styles: “On the one hand [meaning Homer], externalized, uniformly illuminated phenomena, at a definite time and in a definite place, connected together without lacunae in a perpetual foreground; thoughts and feelings completely expressed; events taking place in a leisurely fashion and with very little suspense. On the other hand [in the Old Testament], the externalization of only so much of the phenomena as is necessary for the purpose of the narrative, all else left in obscurity; the decisive points of the narrative alone are emphasized, what lies between is nonexistent; time and place are undefined and call for interpretation; thoughts and feelings remain unexpressed, are only suggested by the silence and the fragmentary speeches; the whole, permeated with the most unrelieved suspense and directed toward a single goal (and to that extent far more of a unity), remains mysterious and ‘fraught with background.’” (1)

Krasznahorkai and Tarr clearly can’t be identified with either of these styles — unless, perhaps, one tries to combine them into some sort of shotgun marriage between, say, Homeric uniformity and suspense, or between allegory and unbroken continuity. As I’ve already suggested, it can’t be said to address Stalinism directly in the way that Light in August addresses Christianity, even though Stalinist bureaucracy and its bureaucratic surveillance, seemingly motored exclusively by mean-spirited self-interest and giving rise to a form of universal misanthropy, is one of its major sources of black comedy.But in spite of all this, Light in August and Sátántangó both qualify as moral indictments of hypocritical communities, a major source of their common power. In any case, it’s important to recall that the narrative of Sátántangó originated with Krasznahorkai, not with Tarr; and a 2012 interview with the former by Paul Morton concludes with a different spin on the issue of a possible Faulknerian influence: Question: “Finally, American readers will surely make comparisons between Sátántangó and Faulkner’s novels.There are the long, rhythmic sentences. There is the small dying town cursed by a past and the constant jarring shifts in time. Did Faulkner’s novels, either in English or Hungarian translation, or any of our other writers inform your work?” Without clarifying whether he read Faulkner in English or in Hungarian translation –- and before going on to praise Dostoevsky, Pound, Thoreau’s Walden, West’s Miss Lonelyhearts, and Thomas Pynchon –- Krasznahorkai replied, “Yes, they had an extraordinary effect on me and I am glad to have the opportunity of admitting this to you now. The influence of Faulkner -– particularly of As I Lay Dying and The Sound and the Fury — struck an incredibly deep echo in me: his passion, his pathos, his whole character, significance, the rhythmical structure of his novels, all carried me away. I must have been 16-18, I suppose, at one’s most impressionable years. […]”(2)

***

Although the film Sátántangó is rigorously faithful to the novel’s narrative and its narrative structure in most respects, one key difference is the exposition of the enlistment/induction -– or, more precisely, re-enlistment and re-induction –- of Irimiás as a government spy (along with his sidekick, Petrina), which occurs in the second chapter of the novel, shortly after the release of Irimiás and Petrina from prison, but which we learn about in the film only retroactively and quite late in the proceedings, in the penultimate chapter. Both novel and film feature a dialogue with a captain/chief about their summons and their obligation to do government work, but in the film, the nature of this work is far more opaque and nonspecific; in the novel, there is a direct admission that their “job is to supply information”. (3) Existentially, this puts us in a very different position regarding the failed farm collective who stand at the story’s center, whose trust in Irimiás we’re encouraged or at least permitted to share in the film, whereas in the novel we can only regard them throughout as gullible suckers and deluded victims of this false messiah’s charisma. This suggests that, as Krasznahorkai’s first novel and Tarr’s sixth feature, Sátántangó represents something notably different in their respective careers — even after we add that the overall artistic evolution of both careers seems to veer increasingly towards allegory, a development culminating in The Turin Horse (which Tarr has declared will be his final film).The fact that the Soviet rule of Hungary was still in force when the novel was written but not when the film was made is already a major difference, even though both Tarr and Krasznahorkai have tended to downplay this distinction in the interviews with each that I’ve encountered.

More generally, the metaphysics of novel and film can’t be the same because sentences can pass back and forth between the physical and the metaphysical, but camera movements are perpetually and necessarily mired in the physical. Dan Gunn claims in his review of the novel for the Times Literary Supplement (June 1, 2012, p. 19), “What starts as a sentence happening inside one character’s head ends inside the stagnation of a puddle or the terror of a cat; the object -– a door or a road or a bell –- can and does become the actor in its own drama.” Perhaps this is a bit hyperbolic, but it does convey the sort of wayward drift that a sentence by Krasznahorkai can take, and clearly a drift of this kind isn’t available to a camera and/or microphone in the same fashion. Tarr can only witness or accompany the physicality of an actor/character, and metaphysical or psychological omniscience can figure only in the brief, third-person voiceovers that conclude some of the chapters. (Similar disembodied male voiceovers take over briefly at privileged moments in The Turin Horse, signaling once again an acknowledgment of the narrative’s literary origins.)

Both Light in August and Sátántangó qualify as metaphysical and allegorical reveries about the perversion of Christianity and fallen mankind, but the former holds out some form of hope for an earlier model of grace and acceptance, Lena Grove, associated with ancient Greece, while the latter, distributing its pessimistic despair more equitably and universally among its characters, implicitly refuses to categorize any of them as heroes or villains, or even as positive or negative role models. Irimiás may be a shabby con-artist and the villagers deluded fools for trusting him, but there is arguably nothing in the novel or film that suggests they should have given up on the notion of salvation and therefore trusted no one; the speech or sermon delivered by Irimiás over the corpse of Esti may be partially insincere and inadequate in other ways as a form of moral guidance, but it is arguably better than nothing, just as Hightower’s well-intentioned impotence and defeat, however abject, might be regarded as morally preferable to the alcoholic doctor in Sátántangó who concludes the film by physically shutting out the external world as he boards up his windows.

Whatever his ideological limitations as a white Southerner, Faulkner ultimately viewed racism as a metaphysical blight on mankind that turns the racially undefined Joe Christmas into a crucified Christ figure. By contrast, Krasznahorkai and Tarr appear to regard the Hungarian hatred of Gypsies mordantly, as an enduring and even comic-absurdist part of the social landscape (such as when the villagers go to the trouble of dismantling their useless furniture so that the Gypsies can’t repossess it before they follow Irimiás to the manor house), but as little more than a glancing detail in their overall abjection (as it appears to be with the father and daughter of The Turin Horse), not as any cinching piece of evidence in their fallen state.

It’s worth adding that the abjection and miserablism of Sátántangó have become so internalized that its ultimate horror becomes the irrelevance of solipsistic fantasy: the death of Esti (“She brushed the hair from her forehead, put her thumb in her mouth, and closed her eyes. No need to worry. She knew perfectly well her guardian angels were already on the way”) (4) or the doctor listening to the “nervous conversation” between his domestic possessions (creaking sideboard, rattling sauce-pan, sliding china plate) in the novel’s concluding sentence. (5) The horror of Joe Christmas’s death, on the other hand, expands and even ascends to become an imperishable memory surviving in the society that produced it:

[…] Then his face, body, all, seemed to collapse, to fall in upon itself, and from out the slashed garments about his hips and loins the pent black blood seemed to rush like a released breath. It seemed to rush out of his pale body like the rush of sparks from a rising rocket; upon that black blast the man seemed to rise soaring into their memories forever and ever. They are not to lose it, in whatever peaceful valleys, beside whatever placidand reassuring streams of old age, in the mirroring faces of whatever children they will contemplate old disasters and newer hopes. It will be there, musing, quiet, steadfast, not fading and not particularly threatful, but of itself alone serene, of itself alone triumphant. (6)

The common thread in both apocalyptic visions is the moral specter of spirituality and acceptance — Christian, post-Christian, or (in the case of Lena Grove), pre- Christian — in the face of nihilistic evil and destruction. Even if it’s just a ghost in the (paradoxically) atheistic universe of Krasznahorkai and Tarr, the persistence of that ghost in the very terms of their vision shouldn’t be confused with its absence.

End Notes

1. Auerbach, Erich, Mimesis: The Representation of Reality in Western Literature, translated by Willard R. Trask, Fiftieth-Anniversary edition, Princeton/Oxford: Princeton University Press, 2003, 11-12.

2. “Anticipate Doom: The Millions Interviews László Krasznahorkai,” by Paul Morton,” http://www.themillions.com/2012/05/anticipate-doom-the-millions-interviews-laszlo-krasznahorkai.html, posted on May 9, 2012.

3. Krasznahorkai, László, Satantango, New York: New Directions, 2012, 27.

4. Ibid., 131.

5. Ibid.,274.

6. Faulkner: Novels 1930-1935 [As I Lay Dying, Sanctuary, Light in August, Pylon], New York: The Library of America, 743.

Published on 13 Apr 2013 in Notes, by jrosenbaum