My fourth bimonthly column for Cahiers du Cinéma España, this ran in their December 2007 issue (no. 7). — J.R.

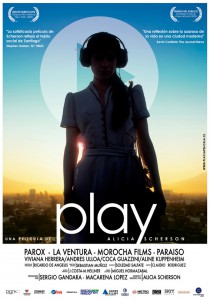

I’ve been reflecting lately about the attractions and perils of internationalism, which bring up the matter of the attractions and perils of nationalism as well. As a child of the Paris Cinématheque (1969-74) who had to see most silent films there without intertitles, following Henri Langlois’ vision of cinema as a universal language, I was both charmed and awed when I met an Argentinian schoolteacher, in Mar del Plata in 2005, who told me about the network of small-town ciné-clubs in Córdoba he helped to run that projected DVDs of such films as Forugh Farrokhzad’s The House is Black (1962) and Kira Muratova’s Chekhov’s Motifs (2002) with Spanish subtitles for 800 or more viewers per week. A utopian undertaking in which quintessential Iranian and Russian films became available to rural Argentinians, this conjured up for me Langlois’ notion of cinema as a separate nation in its own right. So when several Chilean journalists at the Valdivia International Film Festival asked me last October what I thought of the Chilean film industry, the question sounded as weird as my asking a Chilean visiting Chicago what he or she thought of the American postal system. As someone whose knowledge of Chilean cinema extended no further than Raúl Ruiz and Alicia Scherson’s Play, I couldn’t begin to reply.

More recently, preparing to lecture on Stars in My Crown (1950) in a course I teach about 50s world cinema in Chicago, I was irritated as an American to find Jacques Lourcelles describe this film in his Dictionnaire du Cinéma as “the second of Jacques Tourneur’s six westerns and the first of the three that he shot with Joel McCrea”. After all, the fictional late-19th-century town of Walesburg, where the entire film is set, is clearly southern, where memories of slavery are still prevalent and a local group of vigilantes in white sheets that suggest the Ku Klux Klan is still operative.

But further reflection made me speculate that perhaps it was myself and not Lourcelles who was being provincial. Tourneur chose to be quite non-specific in his depiction of Walesburg as a southern town, with no regional accents; and I have no trouble accepting Tourneur’s Wichita (1955) in which McCrea stars as Wyatt Earp, as a western, even though it’s set in Kansas, a midwestern (as opposed to western) state. Perhaps the issue is whether we accept the western as a national or an international genre. If it belongs more to world cinema than to American cinema, the status of Walesburg as a southern town arguably becomes secondary.

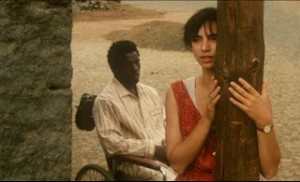

As far as Tourneur is concerned, this issue becomes highlighted if we consider how much is lost as well as gained when Pedro Costa “remakes” Tourneur’s I Walked with a Zombie (1943) as Casa de Lava (1994) by shifting the locale from a Caribbean island to Cape Verde, raising the question of how much the essence of the original film depends on regional details. (The music, for instance, is quite different.)

And what if we consider the issue of locale semiotically rather than geographically or historically? In I’m Not There — Todd Haynes’ recent speculative essay about the semiotic meaning of 60s counterculture as perceived through the figure of Bob Dylan — personal identity is nothing more than overlapping mythologies embodied by six separate actors. One of these, suggested by the myth of Pat Garrett and Billy the Kid (Peckinpah’s 1973 western, in which Dylan costarred), plants Richard Gere in the midwestern village of Riddle, Missouri, a “western” town so fanciful that it includes a giraffe and an ostrich as well as hippies and Pat Garrett. But if what we mean by “the western” is a confused mythology filtered to us through the media, perhaps Haynes’ Riddle is no more outlandish than Tourneur’s Walesburg.