From Cinema Scope issue issue 60, Fall 2014. — J.R.

DVD AWARDS 2014

XI edition (Il Cinema Ritrovato, Bologna)

Jurors: Lorenzo Codelli, Alexander Horwath, Mark McElhatten, Paolo Mereghetti and Jonathan Rosenbaum, chaired by Peter von Bagh

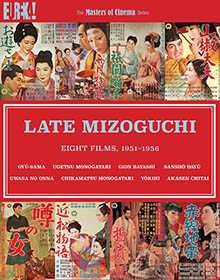

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON BLU-RAY:

Late Mizoguchi – Eight Films, 1951-1956 (Eureka Entertainment). The publication of eight indisputable masterpieces in stellar transfers on Blu-ray is a cause for celebration. If Eureka is not exclusive in offering these individual titles, what makes this collection especially praiseworthy and indispensable is the scholarship, imagination and care that went into the accompanying 344-page booklet. Over 60 rare production stills are included, many featuring Mizoguchi at work. Striking essays by Keiko I. McDonald, Mark Le Fanu, and Nakagawa Masako are anthologized along with extensively annotated translations of some of the key sources of Japanese literature that inspired some of Mizoguchi’s late films. The volume closes with tributes to the great director written by Tarkovsky, Rivette, Godard, Straub, Angelopoulos, Shinoda, and others. Tony Rayns provides spoken essays and some full-length commentaries.

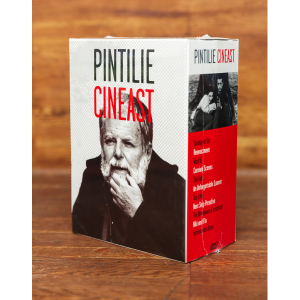

BEST SPECIAL FEATURES ON DVD:

Pintilie, Cineast (Transilvania Films). An impeccable collection devoted to eleven films by an important and neglected maverick Romanian filmmaker, masterful and acerbic, with invaluable contextualizing extras concerning his life, work, and career drawn from ten separate sources. Among the remarkable and ambitious features are Reconstruction (1968), The Oak (1992), and An Unforgettable Summer (1994).

BEST REDISCOVERY:

Ikarie XB 1 (Second Run DVD). An almost forgotten gem, inspired by a Polish novel by Stanislaw Lem and originally butchered in the West, is rightly considered by Joe Dante “a groundbreaking celestial saga.” It had a strong impact on major SF works of the ’60s and ’70s such as Kubrick’s 2001, and Second Run offers a stunning restoration of the uncut version, plus some scholarly essays.

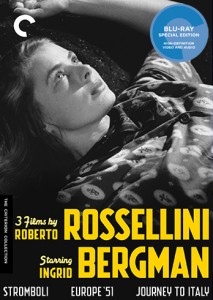

BEST BLU-RAY BOX SET:

3 Films by Roberto Rossellini Starring Ingrid Bergman (Criterion). A superb, definitive edition of three very personal masterworks, with a good many critical, biographical, and historical supplements by many of the best Rossellini scholars and critics, including Adriano Aprà, Richard Brody, Fred Camper, Elena Dagrada, Tag Gallagher, Dina Iordanova, Laura Mulvey, James Quandt, and Paul Thomas, not to mention pertinent contributions by Guy Maddin, Martin Scorsese, and both Rossellini and Bergman and many family members.

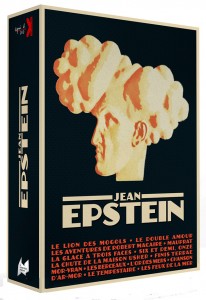

BEST DVD BOX SET:

Coffret Jean Epstein (La Cinémathèque Française, Potemkine Films). Produced by Potemkine Film, the Cinémathèque Française, and Agnès B., the Jean Epstein DVD box set offers for the first time an opportunity to follow the cinematographic path of the French director. With the films made under the Film Albatros label (1924-1925) as a starting point, the review continues with Epstein’s own productions (1926-1928) and those directed in the period from 1928 to 1948, a series characterized by freedom from financial or narrative constraints. Every film included has been restored and musical accompaniments, written specially for this edition, accompany the selection of silent films. A series of supplements and a profusely illustrated 160-page book completes the set of eight DVDs.

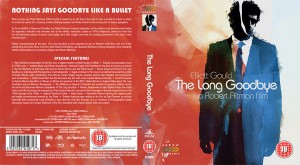

BEST PUBLISHING STRATEGY BY A LABEL:

Arrow Video, an excellent new label in the UK, has already given us exemplary editions, with many thoughtful and valuable extras, of several features, including Robert Altman’s The Long Goodbye, Donald Cammell’s White of the Eye, Don Siegel’s The Killers, and many Brian De Palma films.

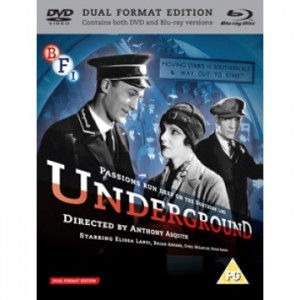

BEST BLU-RAY:

Underground (BFI). Young Anthony Asquith’s “story of ordinary workaday people,” conceived near the end of the silent era, is getting a well-deserved second breath due to a gorgeous BFI restoration. This dual-format edition, in both high definition and standard definition, offers many background materials, including rare shorts tracing a cultural history of the British underground train system.

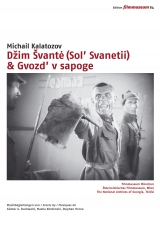

BEST DVD:

Džimn Švantė (Sol’svanetii & Gvozd’ v sapoge) (Edition Filmmuseum). As part of the series edited for the Filmmuseum collection, the Cineteche of Munich and the Filmmuseum of Vienna in association with the National Archives of Georgia at Tbilisi have join efforts to rescue from oblivion two unknown films by Mikhail Kalatozov, whose cinematographic path still has some parts that remain in the dark. The first film, Džimn Švantė (Salt for Svanetia), directed in 1930, is a reconstruction of the harsh daily life conditions of the Caucasus mountain peasants. The second title, Gvozd’ v sapoge (A Nail in the Boot) from 1932, is a parable about the lack of responsiveness in times of war, constituting a dreadful anticipation of the Stalin regime purges. Both films were restored for the occasion and furnished with a musical accompaniment and subtitles in Georgian, German, and English. The edition includes a 16-page booklet, also bilingual (in German and English).

The jurors would like to stress that none of us is in a position to know all the important DVD releases, even though all of us have encountered important examples, some of which were not nominated for awards but deserve in any case to be far better known, so each of us has selected one or more personal favourites that he would like to recommend.

Lorenzo Codelli’s personal choice is an innovative online museum organized by the city of Valencia which allows visitors to enjoy the complete works of Luis Garcia Berlanga: berlangafilmmuseum.com.

Alexander Horwath’s personal pick is Pod značkou bat’a, a three-DVD box set co-published by the Czech National Film Archive with a huge number of shorts made by the Bat’a Corporation in the City of Zlin. It’s a wonderful example of a non-cinema company making public their archive of films.

Mark McElhatten wants to cite the ongoing devotion shown in publishing the extraordinary films of Werner Schroeter in DVD releases by Edition Filmmuseum Munich. Recent releases have included Willow Springs paired with Day of the Idiots and Der Bomberpilot with Nel Regno di Napoli, both releases with many extras. He also wishes to recognize the importance of the underexposed films of Peter Thompson made available through the valiant efforts of Chicago Media Works.

Paolo Mereghetti has selected Alberto Cavallone’s Blue Movie, released on Raro Video.

Jonathan Rosenbaum would like to cite two releases: Peter Thompson: 6 Cinematic Essays & 2 Interviews (Chicago Media Works, US) and Alain Resnais and David Mercer’s Providence (Jupiter Film, France). He hastens to add that while he helped to conduct both of the two interviews with the late Peter Thompson included in this set, he originally became friends with Thompson because of his enthusiasm for the passionate originality and beauty of his work. The belated release of one of Resnais’ greatest features includes both the English and the French-dubbed versions (which Resnais supervised), and many fascinating extras, with English subtitles.

Finally, Peter von Bagh has selected Fritz Lang & L’Amérique – 2 Films de Fritz Lang: While the City Sleeps and Beyond a Reasonable Doubt, a DVD box set from Wild Side that includes a 120-page book by Bernard Eisenschitz, La nuit américaine de Fritz Lang.

***

Among the worthier award finalists that didn’t get awards (not counting the Thompson box set, copies of which reached the jurors too late to be considered, and StudioCanal’s Jacques Tati L’intégrale, which was never sent to us at all)—and this is a highly selective and personal list — are Peter Emanuel Goldman’s Echoes of Silence (1964) with the short Pestilent City (1965), and Wheel of Ashes (1968) with 24 minutes of 8mm Reels (1965), on separate Re:Voir DVDs, each with substantial bilingual booklets, and Lost and Found: American Treasures from the New Zealand Film Archive, with work by John Ford, Alfred Hitchcock, Graham Cutts, Mabel Normand, Norman Taurog, and Lyman Howe—a National Film Preservation Foundation DVD, also with a good-sized booklet.

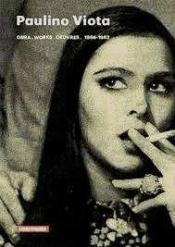

I’m grateful to Intermedio in Spain, already responsible for the splendid Pere Portabella box set, for sending me Paulino Viota Complete Works 1966-1982, another DVD box set finalist, with English subtitles for the features as well as a detailed bilingual booklet. But I also have to confess that finally catching up with Viota’s furtive and clandestine experimental feature Contactos (1970) after many decades of hearing about it, I was quite disappointed, and actively annoyed by his 10-minute Duración, made the same year, which focuses on a clock face throughout and must have seemed tiresome and obvious even in 1970 Franco Spain. Maybe Viota’s recent introduction to the latter film and his post-screening discussion about it would provide me with some context, but the compilers of this package have opted to leave both of these untranslated, along with Viota’s lecture about John Ford’s Rio Grande (1950) and other bonus features, which has dissuaded me so far from delving into Viota’s two other features here, which are subtitled.

So I’m even more thankful to Intermedio for sending me Adolpho Arrieta Complete Works 1966-2008, another four-DVD box set devoted to “underground” work, but in this case with English subtitles for everything and a substantial trilingual booklet (in Spanish, French, and English) with heady texts by Jean-Claude Biette, Marguerite Duras, Pierre Léon, Serge Bozon, and Jonas Mekas, among others—another item released too late to qualify as an awards finalist. Unlike Viota, I’d never heard of Arrieta before, though most of his work that I’ve seen so far is truly revelatory. Some of this may be attributable to familiar faces, voices, and places—Jean Marais as the lead in Le Jouet criminal (1969), Françoise Lebrun in the 1972 Pointilly (the focus of the Duras text), Marlene Dietrich singing “You Go to My Head,” the St-Germain-des-Prés neighbourhood during the same period I was living there—but what Arrieta is doing with these sacred emblems, not to mention the transvestites and other characters in Las intrigas de Sylvia Couski (1974) and Tam Tam (1976), at claustrophobic parties and on the street, is no less part of the magic. (Severo Sarduy has described the latter two films, made before Arrieta eventually returned to Madrid in 1989, as French punk films, even though the latter was at least partly made in Manhattan.) For Biette, who also worked on some of the director’s skeletal crews, Arrieta’s films “are not too distant from those of Jean Rouch and Jacques Rivette,” while Mekas’ cross-references are, no less predictably, Warhol and Jack Smith. All these labels and comparisons make some kind of sense to me—even when my attention starts to flag after the party patter in Tam Tam becomes too parodically mannerist—but the degree to which Arrieta’s films aren’t so much inhabited as haunted by their subjects makes me want to return to them, again and again.

Next are some other worthy or notable recent releases that, for one reason or another—although almost always due to ignorance about their existence—didn’t make our list of contenders:

Alberto Toscano’s English translation of Franco Fortini’s 1967 essay I cani del Sinai—published in hardcover in 2013 by Seagull Books and available from both University of Chicago Press and Amazon—includes, along with a foreword by Luca Lenzini, an afterword by Toscano, and Fortini’s 1976 “A Letter to Straub” and 1978 “A Note for Jean-Marie Straub,” a DVD containing Straub and Danièle Huillet’s 83-minute film devoted to this essay, Fortini/Cani (1977), with English subtitles. This is their ninth film and their first major landscape work (unless one counts the 1975 Moses und Aron); it’s also the first film of theirs to have been rejected by the New York Film Festival, apparently for ideological reasons. My thanks to Richard Porton for alerting me to this major release.

Criterion’s dual-format release of Georges Franju’s strangest feature, Judex (1963)—not so much a proper homage to the 1916 Louis Feuillade serial as an appreciative reconfiguration of some of its basics, including its charm and period flavour—has been garnering more praise and understanding than it did when it was first released in theatres, at a time when the impact of Susan Sontag’s “Notes on Camp” in North America seriously clouded and irrelevantly distorted the film’s reception. But another key reason for welcoming this package is that it contains Franju’s two greatest shorts after Le Sang des bêtes (which is already available on Criterion’s separate Blu-ray and DVD editions of Eyes Without a Face), Hôtel des Invalides (1951) and Le grand Méliès (1952). I’ve been eagerly awaiting an English-subtitled version of the former film, perhaps the subtlest and most devastating work in the entire Franju canon, for many years now, and re-seeing it now it becomes even more apparent that it must have exerted a major influence on Forough Farrokhzad’s The House is Black, made a decade later.

The last time I saw Milos Forman’s Taking Off (1971), his first feature in the US, was when it premiered, either at the New York Film Festival or at Cannes (where it won the Grand Prix). I had some trouble connecting with it back then, perhaps because I was too old to relate to the film’s teenage runaways yet too young and bohemian to relate to the freaked-out middle-aged parents (who include Lynn Carlin, post-Faces, and Buck Henry, post-The Graduate). But after getting a recommendation from my friend Jean-Jacques Birgé in Paris and subsequently learning that the film wouldn’t get released at all in North America due to some mishegas involving music rights, I picked up the French Blu-ray (which includes two making-of extras, one in English and one in French), saw the film again, and enjoyed it more this time. I also discovered that it’s always been a film about the parents, not really about the teenagers, whom Forman and cowriter Jean-Claude Carrière regarded as fairly inscrutable (although there’s a lot of audition footage involving the latter—inspired and prompted, I discover from the extras, by Forman’s first Czech feature).

Frank Borzage’s Man’s Castle (1933), probably his greatest sound feature, can be found on DVD in Spain as Fueros Humanos (only 7,95 Euros plus postage from Spanish Amazon), but, as far as I know, nowhere else. It isn’t a restoration and there aren’t any extras, but the print is fairly decent apart from a few seconds that are missing (Spencer Tracy diving nude into a lake, if I remember it correctly), and you can remove the Spanish subtitles if you want to. This came out a couple of years ago, but as far as I’m concerned, its availability is still big news.

Erich von Stroheim’s Greed (a.k.a. Les Rapaces), from “http://www.bachfilms.com” www.bachfilms.com, in a box set including two DVDs, a separate CD of the new original score composed and performed by the Panama Hammer Jammers (confusingly billed on the box as “La bande originale du film,” as if someone was actually playing this music back in the 1920s), and five lobby cards. A mixed bag (or box) in more ways than one, this is the only commercially available digital version of Greed I’m aware of apart from the equally unrestored Spanish version, Avaricia, which comes with no extras. The extras here, all in untranslated French, include a 27-minute collection of stills from missing scenes (certainly not all the missing scenes, as a French intertitle implies), four minutes of silent footage chronicling the Death Valley shoot, a 51-minute documentary about Stroheim, a 26-minute documentary about Stroheim and Carl Laemmle, and an interview with film historian Agnès Michaux.

Like Greed and The Magnificent Ambersons, Jean Renoir’s 1934 Madame Bovary, on a Gaumont DVD, is an eviscerated adaptation of a great novel by a great filmmaker. In this case, Renoir made a three-and-a-half-hour film that the distributor forced him to reduce by a third; Renoir, who persuasively argued that the surviving film is more boring than the original, also proudly noted that Bertolt Brecht was among those who saw and was enchanted by the pre-release version. As Alexander Sesonke observes, it’s mainly the everyday and less plot-driven details that got eliminated, but the film, or what remains of it, certainly has its compensations, including a score by Darius Milhaud. This Gaumont edition is typically neither a restoration nor provided with English subtitles, but for those like me who have an easier time reading French than understanding it when it’s spoken, the French subtitles for the hearing impaired are very helpful, and they’re even colour-coded: yellow for off-screen dialogue, red for sound effects.

There’s an ambitious and exciting new series of DVDs presented by Bertrand Tavernier and Patrick Brion called Western de Legende, and I picked up three of its titles in Paris: Hugo Fregonese’s Apache Drums (a.k.a. Quand les tambours s’arrêteront, 1951) and The Raid (a.k.a. Le Raid, 1954), and Budd Boetticher’s Buchanan Rides Alone (a.k.a. L’Aventurier du Texas, 1958). All three are beautiful restorations prefaced by lengthy and unsubtitled introductions by Tavernier and Brion. I was especially gratified to hear Tavernier begin his 25 minutes about Apache Drums by calling it, “without exaggeration, a masterpiece”; even though this may be an overstatement, I find it preferable to Manny Farber calling it “the last and least of [Val Lewton’s] works.” It’s obviously Lewton’s last film, as well as his only one in colour—and Farber was clearly bothered by the expressionistic use of this colour, especially when it came to Apache war paint, which he compared to Radio City Music Hall makeup—but “the least” is a distinction that I’d much sooner assign to the truly awful 1950 MGM comedy Please Believe Me, which Farber presumably (and wisely) missed. Tavernier overall makes a very plausible case for Apache Drums’ many merits, even arguing that Lewton found “the same sort of complicity” with Fregonese at Universal that he previously found at RKO with Jacques Tourneur.

The Raid, less appealing visually, has plenty else to keep it interesting, both historically and dramaturgically: Sydney Boehm wrote the script, and the cast includes a better-than-usual Van Heflin, an almost unrecognizable Anne Bancroft, and Lee Marvin, among others. And Buchanan Rides Alone, bien sûr, is an eminently rewatchable classic—a sort of deadpan existential comedy in which moral alliances are made to seem both relaxed and almost arbitrary, yet decisive.

A single French Blu-ray including Jean-Luc Godard’s authorized One Plus One and unauthorized Sympathy for the Devil (1969) features not only a detailed account of the differences between the two versions, but also trailers, a photo gallery, detailed raps (untranslated) by Jean Douchet and Christophe Conte, a 14-page booklet devoted to French critical responses to the film between 1969 and 2008 (including a brief 2004 statement by Olivier Assayas), and, best of all, Voices (1968), a 43-minute “making-of” documentary by Richard Mordaunt in English that I’d never heard of before; it includes a lot of interview material as well as footage of Godard directing, mostly in English.

***

Other recent acquisitions, all from the US, alphabetically arranged:

Armored Attack! (Lewis Milestone, 1957). I’m certainly glad that Olive Films includes Milestone’s original 1943 The North Star on this Blu-ray along with Armored Attack!, the mutilated Cold War tract that was spun out of it 14 years later, which removes roughly half an hour of happily cavorting Ukrainian peasants (played by Dana Andrews, Anne Baxter, Walter Brennan, Farley Granger, Ann Harding, Walter Huston and Jane Withers, among others), along with their uses of the word “comrade” and most of their pseudo-folk ditties and dances (with music by Aaron Copland and English lyrics by Ira Gershwin), and adds a strident anti-Communist narration that tells us exactly what to feel and think about the Russian leaders as well as the German invaders and their aforementioned Ukrainian victims. The North Star is admittedly pretty bad on its own terms, but it still has a lot to teach us about what grotesque over-polishing can do to noble ambitions, even enlisting the services of James Wong Howe to gild all the pastoral lilies. One also has the pleasure of seeing Erich von Stroheim as a “liberal” Nazi surgeon in both versions, not to mention some effective if studio-contrived combat footage from Milestone. I guess you might call it an instructive mess in both versions, but The North Star, which managed to garner loads of prestige (including half-a-dozen Oscar nominations) in the mid-’40s, is far more instructive.

Dorothy Darr and Jeffery Morse’s Charles Lloyd: Arrows into Infinity (2013), on a Blu-ray from ECM (which means, in this case, excellent sound). A good if not great tenor saxophonist and flutist, Lloyd comes across in this documentary as an exceptional performer and a magnificent person, in many ways both a child and a father in relation to the countercultural ’60s. His legacy plainly has a lot to do with the spiritual strength derived from shunning the macho competitive impulse that has plagued jazz tradition with such rituals as “cutting contests” for the sake of channeling others; significantly, he explains shifting early in his career from alto to tenor sax because of his admiration for John Coltrane, Sonny Rollins, and Lester Young, his models (and by no means his equals), while many other musicians would have preferred to avoid such direct emulation. Partly for this reason, Lloyd is the sort of jazz musician who can win over many listeners who aren’t jazz buffs. This film, co-directed by his artist wife with a lively sense of how to match her husband’s eclectic inventions in terms of shooting, editing, and even processing her material (also drawing on an excellent assembly of concert and studio archival footage), does a fine job of sketching out the unconventional arc of his career, which led him to escape the public sphere at the height of his fame, like Greta Garbo (as critic Stanley Crouch observes), to pursue a more meditative existence. The common sin of most jazz documentaries—to smother the music with talk after sampling a few bars of it straight—is not entirely absent here, but at least Darr and Morse negotiate this practice with some tact and grace, especially when it comes to charting Lloyd’s personal encounters with such musician-soulmates as Michel Petrucciani, Ornette Coleman, Billy Higgins, and Jason and Alicia Hall Moran (as well as archival footage of Keith Jarrett and Jack DeJohnette from earlier phases of Lloyd’s career). In short, what ultimately redeems this documentary is its’60s wisdom—not so much about how to make music as about how to live.

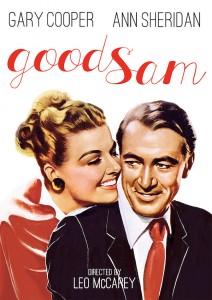

Leo McCarey’s Good Sam (1948), on another Olive Blu-ray, may be the most neglected masterpiece in the entire McCarey canon, although it’s commonly regarded as a failure, even as a disaster. (In fact, it enjoyed a modest commercial success.) In some respects it’s McCarey’s most serious and profound movie, even though it’s ostensibly a comedy: a sustained look by a devout Catholic filmmaker at the disastrous consequences that can ensue from someone actually following the Gospels. It’s clearly one of McCarey’s most personal efforts, made by his own production company, but it’s closer to being an investigation of its troubling subject—and reportedly a personal autocritique as well—than the propounding of any conclusive thesis, which is part of why I treasure it as much as I do (and why I suspect some other viewers don’t). Gary Cooper plays the eponymous lead to perfection, and Ann Sheridan as his suffering wife Lu is just as good.

In trying to account for this film’s poor reputation, I wonder if the characteristic McCarey trait of laughter becoming indistinguishable from tears has been pushed so far in this case that it seriously confuses some of our emotional responses. The film identifies sanity mainly with Lu’s “realism” and heroic forbearance while surviving and/or cleaning up the messes left by Sam’s goodness (or perhaps only his “goodness,” which is almost never defined in relation to “realism”), but this balance is unexpectedly and dramatically reversed during the film’s closing stretches. It’s also significant that in the first of Lu’s big scenes with Sam, she’s laughing hysterically at the latest of his messes (a wonderful scene); in the second, she’s sobbing; and in the film’s final scene, set during the Christmas season, we can’t even tell whether she’s laughing or sobbing.

Most of the time, McCarey adopts and asks us to share Lu’s ambivalent viewpoint, but his tragicomic view of things is far from cynical, even though Sam’s world is largely inhabited by selfish and sometimes mean-spirited freeloaders, some of whom capitalize on his kindness and some of whom actively resent it—but then again, some of these characters wind up surprising us. Finally, I think this film demands to be read as McCarey’s complex response and “reply” to the desperation of Capra’s It’s a Wonderful Life, made two years earlier, and as such, I think it offers a far more persuasive and nuanced view of the human condition in all its ambiguities and complexities than Capra’s more Manichean universe.

Grand Hotel (1932), on a Blu-ray from Warners. Probably held back by my auteurist preferences, I’ve taken my time in getting around to watching this hoary star classic for the first time, but the loss was mine. As someone who has so far resisted much of the Garbo mystique, I can now belatedly see, in her ecstatic rendition of a smitten Russian ballerina, what all the justifiable fuss was about, and John Barrymore’s suaveness in winning her over is no less sublime. Equally impressive in their own fashions are Joan Crawford as a flirtatious and practical-minded stenographer, Lionel Barrymore as a dying bookkeeper on his last fling, and even Wallace Beery as a Germanic heavy.

Intolerance (1916), in a two-disc Blu-ray set from the Cohen Film Collection. Considering how steeped I am in the aesthetics of Feuillade’s serials during the teens, I find the preachiness of Griffith—even when he’s at his most adventurous, epic, and scenic, as he is here—a bit hard to put up with, so I blush to admit that I have a much better time with Feuillade’s breezy Judex, made the same year. But this tinted digital restoration with a Carl Davis score, with many major extras—including the two 1919 features Griffith largely extracted from Intolerance, The Fall of Babylon and The Mother and the Law, a recent recitation of some favorite anecdotes by Kevin Brownlow, and helpful printed essays by William M. Drew and Richard Porton—is probably as good a presentation as one might hope for.

Martin Gabel’s The Lost Moment (1947), on a Blu-ray from Olive Films. This is the only film Gabel ever directed, an adaptation of Henry James’ The Aspern Papers that intermittently overcomes its casting problems (including Robert Cummings as the lead) with some pretty good Gothic touches. But I can’t take this seriously as a James adaptation, for the same reason that I have some issues with the late Eduardo de Gregorio’s almost impossible-to-see 1984 Aspern. As I had occasion to write recently about the latter film, “James, a master of indirection, concludes his first chapter with the hero joking to a friend and confident, before arriving at the villa, that he will have to ‘make love to the niece,’ and the friend replying, ‘Ah, wait till you see her!’—which clearly, if tactfully, implies that the niece is unattractive. So even though the niece remains the central and most important character in both the novella and the film, she is a far more glamorous and potentially romantic figure in Aspern.” In de Gregorio’s film, this character is played by Bulle Ogier; here she’s played by Susan Hayward, who’s even more inappropriate given that the aunt, who is supposed to have once been very beautiful, is played by Agnes Moorehead, under tons of makeup contrived to make her as hideous as possible. (Aspern at least had the good taste to cast Alida Valli in the role.)

Todd Haynes’ five-part 2011 TV series Mildred Pierce (on a two-disc DVD from HBO) may well be my favourite Haynes work. I’ll have to see it again to be sure, and the audio commentary included here with Haynes, his co-writer Jon Raymond, and his production designer Mark Friedberg gives me an excellent excuse.

Leave it to Jerry Lewis to offer us a deluxe and unshelvable Blu-ray + DVD edition of The Nutty Professor (1963) from Warner Video, built like a doorstop—the most cumbersome single object released since Murnau, Borzage and Fox. But in this case, at least, you can extract a normal-size box containing the dual-format Nutty Professor (with many extras) along with DVDs of Frank Tashlin’s 1960 Cinderfella and Lewis’ 1961 The Errand Boy (both with audio commentaries) and place the other materials elsewhere: a hardcover book devoted to Nutty Professor storyboards, a softcover book devoted to portions of the annotated script, another softcover book written by Lewis expressly for the crew of Nutty Professor (it’s called Instruction Book for “Being a Person”, and one might reasonably ask whether this was written by the Julius Kelp or the Buddy Love side of Lewis’s Jekyll-and-Hyde combo), a relatively disposable CD of Lewis’ Phoney [sic] Phone Calls, 1959-1972, and finally, “A Personal Message from Jerry Lewis” that states, among other things, that he agrees that The Nutty Professor is his best work but finds it hard to call it his favourite.

Brian De Palma’s Obsession (1976), on an Arrow Blu-ray from the UK, is for me one of his better efforts, but credit for that probably goes in part to writer Paul Schrader and composer Bernard Herrmann. Loads of useful extras here, which I’ve come to expect from Arrow releases, include De Palma’s early shorts Woton’s Wake (1962) and The Responsive Eye (1966).

André De Toth’s The Other Love (1947) on yet another Olive Blu-ray, from the same year as The Lost Moment. It’s hard to think of many De Toth films that aren’t interesting or better than that in one way or another. Working here with a potentially awful tearjerker story derived from Erich Maria Remarque about a celebrated concert pianist (Barbara Stanwyck) suffering from tuberculosis in a Swiss sanitarium, oscillating between the affections of her doctor (David Niven) and a devil-may-care racing driver (Richard Conte), sounds like a recipe for disaster, but De Toth manages to keep it perverse and troubling rather than merely cascading with soapsuds, despite all the proddings of an overwrought Miklós Rósza score.

So This is New York (1948), another Blu-ay from Olive Films. I still haven’t read Ring Lardner’s 1920 novella The Big Town (which you can access for free in its entirety, complete with original illustrations, at HYPERLINK “http://www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/rl/bigtown.html” www.ibiblio.org/eldritch/rl/bigtown.html), but I’ve read enough of his other stories to appreciate that this early and fairly hilarious comedy directed by Richard Fleischer—the first film produced by Stanley Kramer, starring TV and radio comic Henry Morgan—probably captures Lardner’s essence better than any other movie does, including the much better-known Champion, Kramer’s following production. The filmmakers, including co-writers Carl Foreman and Herbert Baker, wisely set the story in its original period while following the misadventures of an Indiana cigar salesman (Morgan) in the Big Apple with his wife (Virginia Grey) and sister-in-law (Dona Drake), whom they’re trying to match up with a suitable husband.It bristles with the cranky wisecracks that are Lardner’s signature, and the others in the cast—including Rudy Vallee, Hugh Herbert, and Leo Gorcey—keep this percolating and agreeably manic.

The Spike Lee Joint Collection, Vol. 1. A pair of Blu-rays from Touchstone consisting of 25th Hour (2002), currently my favourite of Lee’s fiction features, and He Got Game (1998), described by me at the time of its release as “certainly Lee’s best narrative film in years”—although I recall zilch about it 14 years later, possibly because of my systematic sports allergy. Both are outfitted with audio commentaries by Lee and others; 25th Hour is accorded several other bonus items.

The Warners Blu-ray of Paul Thomas Anderson’s There Will Be Blood (2007) is worth mentioning for its imaginative and thoughtful extras, which I’m beginning to expect from Anderson’s digital editions. I won’t tell you what these are because it’s better to discover them on your own. (Who says that spoilers can’t also apply to bonus features?)

We’re in the Movies, a dual-format double feature from Flicker Alley drawn from the Blackhawk Films Collection, offers us two offbeat investigations into fringe phenomena: Iain Kennedy’s recent documentary Palace of Silents: The Silent Movie Theater of Los Angeles, and a package calling itself Itinerant Filmmaking that includes Stephen Schaller’s 1983 documentary When You Wore a Tulip and I Wore a Big Red Rose, Oliver W. Lamb’s 1914 The Lumberjack (the locally-made Wisconsin short that Schaller’s film is about), and other short local films made in rural Tennessee (1918), Pennsylvania (1934), and Texas (1937); a 12-page booklet that offers essays by David John Slaughter (one of the silent theatre’s former employees) and David Shepard (about the local/itinerant films). So far I’ve seen only Palace of Silents, which is awkward as filmmaking but intermittently fascinating for its clips (including diverse glimpses of Los Angeles from several periods) as well as its overall history of the silent theatre over roughly half a century. Curiously, I found the true-crime account of the murder of one of the theatre’s four owners the least interesting part of the narrative; far more intriguing were the various shifts in programing policies and corresponding customers.

Michael Wadleigh’s Woodstock, on a 40th anniversary-edition Blu-ray from Warners, probably offers the best and most accurate glimpse of the positive side of the countercultural ’60s that the movies have to offer. After acknowledging that this 224-minute “director’s cut” is substantially longer than the version I saw at the Cannes premiere in 1970, I would also still argue that this widescreen epic also qualifies as one of the last of the great city symphonies (a form mostly associated with the late silent and early sound periods, although the late Michael Glawogger’s 1998 Megacities qualifies as a later entry), despite the fact that the “city” in Wadleigh’s film is only a temporary gathering in a field. In any case, if you watch this at all, be sure to see it on a big screen.