From the Chicago Reader (February 28, 2003). — J.R.

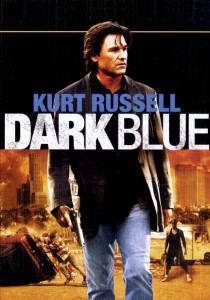

Dark Blue

* (Has redeeming facet)

Directed by Ron Shelton

Written by David Ayer and James Ellroy

With Kurt Russell, Scott Speedman, Brendan Gleeson, Michael Michele, Ving Rhames, Lolita Davidovich, Kurupt, and Jamison Jones.

A curious kind of double game is being played in Dark Blue, a cop thriller that sets out to “explain” the 1992 LA riots. For a good while I sat thinking, “At last — a movie that doesn’t mince words about police corruption and racism,” for even if it’s a decade late and a bit simplistic in some of its moral positioning, the story doesn’t soft-pedal the facts. (It even prompted me to think how useful it might be if someone in Hollywood delivered a thriller about the Enron scandal — not ten years from now but before the next presidential election.) But I soon realized that the attempt to wed a comfortable genre to an uncomfortable social agenda allowed another kind of soft-pedaling to take over.

The filmmakers — Ron Shelton directing a David Ayer script based on a James Ellroy story — obviously want us to swallow a bitter pill, but traditionally Hollywood genres, even the LA cop thriller, are sweet and don’t have much of an aftertaste. Inevitably, bitter and sweet start working at cross-purposes. If Dark Blue were doing its job, the LA riots would be the logical culmination of everything preceding them. Instead they come across as yet another melodramatic contrivance in a story that’s already staggering under the weight of far too many.

Shelton’s style as a writer is more recognizable than his style as a director, especially in his sports comedies Bull Durham, Tin Cup, and White Men Can’t Jump. Now that he’s directing material that isn’t his own, it’s worth asking what drives his choices. My tentative conclusion is that he’s a moralist and that all his best and most characteristic films reflect this interest. Such a notion is prompted less by the sports comedies than by his splendid and noble failure Cobb, which offers a dark look at the underside of those comedies by critiquing the spirit of competition itself.

At first Dark Blue seems cut from the same cloth, but the moral investigation is undermined by the simple, unambiguous categories — virtuous, corrupt, and conflicted — set up for practically all the characters. Clearly virtuous are deputy police chief Arthur Holland (Ving Rhames) and his assistant Beth Williamson (Michael Michele), who are determined to blow the whistle on their corrupt colleagues. So are the antihero’s cop wife (Lolita Davidovich) and their son, whom we barely see at all. Clearly corrupt are two criminals named Frank (Jamison Jones) and Orchard (Kurupt); the alcoholic antihero, third-generation detective Eldon Perry (Kurt Russell) — at least until genre reflexes require him to undergo a conversion, becoming the hero and therefore clearly virtuous; and the thoroughly evil and conniving special investigations squad boss, Jack Van Meter (Brendan Gleeson). Clearly conflicted are Perry’s young sidekick and Van Meter’s nephew, Bobby Keough (Scott Speedman), and Perry himself during the all-too-brief period when he’s turning into the hero. (You know the movie’s in trouble when it uses two little-girl witnesses to trigger a character’s remorse about what he’s doing.) Only Russell, the star, is allowed to move through a range of moral positions — though the simple arc of his development precludes ambiguity, which might impede the momentum of the narrative.

This is all perfectly acceptable, perhaps even necessary, in a certain kind of cop thriller. But it doesn’t reflect reality, which can’t be divided into good guys and bad guys without leaving out lots of essential information. (Our president prefers to leave out the information that former presidents treated a couple of his bad guys like good guys by arming them to the teeth.) And since Dark Blue professes to be concerned with reality — specifically the Rodney King trial and the riots that followed the verdict — it can only founder with characters that are constructed to serve generic functions.

Russell has clearly invested a lot in his mercurial part, and I agree with my colleagues who insist that he’s the best reason to see this film. But I also wonder if a star turn is needed to convey the ruthless duplicity of some LA policemen. Even if we buy the sort of moral conversion this movie postulates, it’s hard to accept Perry’s protracted public confession, a deliberately embarrassing personal display that seems more appropriate to a Frank Capra feel-good exercise or a musical like The Band Wagon than to a social exposé — especially after the movie has spent over an hour relentlessly tracking his cynicism and racism. We’re left feeling that either his initial baseness or his abrupt turnaround has to be bogus, because even though anyone is capable of a moral awakening, the likelihood of it occurring within the space of a single afternoon is slim.

In other words, noticing what a resourceful actor Russell is distracts us from thinking about the LA police force, especially since the film doesn’t make us want to learn anything more about Eldon Perry. The only character I wanted to know more about was Orchard — mainly because he’s the only one in the story who doesn’t seem surprised when the rioting breaks out. Maybe he’s a remorseless killer and a police informant to boot, but he might have had more to tell us than anyone else.