From the Chicago Reader (August 18, 2006). Fox has reissued this film in a two-disc edition, combining a Blu-Ray with a DVD of the film on a second disk — the latter including an audio commentary by writer-director Neil Burger which clarifies and amplifies how well he understands the mechanics as well as the overall concept of his own film. He’s especially enlightening on the subject of late 19th century magic and how he incorporated many of his findings in the film, utilizing the expertise of several contemporary magicians, including Ricky Jay. — J.R.

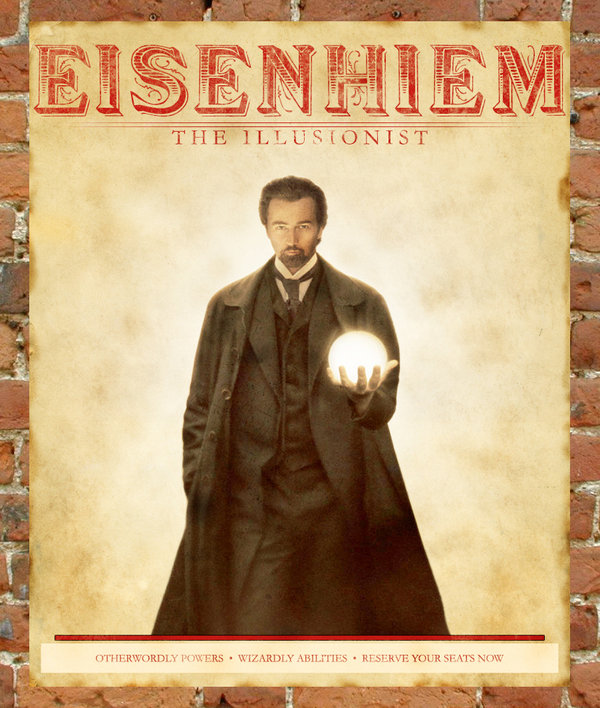

The Illusionist

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Neil Burger

With Edward Norton, Paul Giamatti, Jessica Biel, Rufus Sewell, Eddie Marsan, and Jake Wood

Stories, like conjuring tricks, are invented because history is inadequate to our dreams. — Steven Millhauser, “Eisenheim the Illusionist”

At first glance Neil Burger’s first two features couldn’t be further apart. Interview With the Assassin (2002) is a scruffy-looking pseudodocumentary and thriller about two marginal characters — a young, out-of-work cameraman (Dylan Haggerty) and his 60-ish solitary neighbor (Raymond J. Barry), an ex-marine who claims to have fired the second bullet that killed John F. Kennedy. The Illusionist, based on a story by Steven Millhauser, is a lush piece of romanticism — a tale of enchantment set in turn-of-the-century Vienna about a magician named Eisenheim (Edward Norton), the son of a cabinetmaker, and his longtime relationship with Sophie (Jessica Biel), a duchess and the prospective fiancee of Crown Prince Leopold (Rufus Sewell), an old-fashioned villain.

Obviously the texture and tone of these films are different. But Burger’s exceptional gifts as a storyteller and as a director of actors are fully apparent in both, and he’s up to something similar in both, playing with the imagination and credulity of the viewer. I’m reminded of a statement Orson Welles made to an interviewer in 1938, the year of his War of the Worlds radio hoax, before he started making movies: “I want to give the audience a hint of a scene. No more than that. Give them too much and they won’t contribute anything themselves. Give them just a suggestion and you get them working with you. That’s what gives the theater meaning: when it becomes a social act.”

In Interview With the Assassin Burger uses the whiff of paranoia implicit in the public’s uncertainty about the facts of the Kennedy assassination to encourage us to swing between regarding the ex-marine as a cranky nut and wondering if part of what he’s claiming is true. Or if we regard him as a cranky nut throughout, to still accept the fiction that this character and his cameraman neighbor are real. That they’re both ostensible nobodies and outsiders lusting for power gives us at least one reason to identify with either or both of them, regardless of what we conclude about their reality. The point is that we’re working with Burger, and if we accept any of his invitations, we become implicated in the events as they develop, turning our participation into a social act.

Burger does the same thing in another way in The Illusionist when at the outset he introduces us to the mysterious young magician, whose tricks are so spectacular we’re unsure whether to see them as supernatural miracles or as simply very good magic tricks. We’re also presented with a speculative account of how the magician was first introduced to magic — a whimsical fantasy encounter with another magician that provides more details we must decide whether to believe or doubt. The romanticism of Burger’s depiction of 1900 Vienna (conjured up with an exquisite sense of suggestion and ellipsis) and the love story he’s telling serve the same function as the viewer’s paranoia in Interview With the Assassin: we’re given an elaborate menu of choices, and as we decide how much to believe we’re implicated in some of the political issues raised by Eisenheim’s challenge to Leopold’s power. One spur for us is the score by Philip Glass, the most evocative and compelling movie work of his I’ve heard; it manages to evoke the period yet still sound like Glass.

In The Illusionist we’re less likely to identify with either Leopold or the magician, and more with Inspector Uhl (Paul Giamatti) — a character who feels sympathy for the magician but owes allegiance to Leopold and is therefore divided and compromised. He’s also the story’s only narrator. Giamatti’s performance is subtle, expressive, and richly nuanced. He also gives the character a slight Viennese accent, as Norton does his. Tellingly, Sewell’s accent is much heavier, which according to fairy-tale convention marks him as a villain. As in Interview With the Assassin the suspense underlying the story’s mysteries is the moral suspense concerning our credulity and how we relate to the power or powerlessness of the characters.

One reason we have so many creative choices is the imaginative breadth of the filmmaker. Neither Sophie nor Leopold is in Millhauser’s 21-page story “Eisenheim the Illusionist,” yet Burger’s adaptation is entirely faithful to the spirit of the original. The film also omits things such as any allusion to Eisenheim’s being Jewish, though it isn’t hard to imagine that he is.

The film’s climax is a very deft stretch of pantomime from Giamatti, alternating with brief, silent flashbacks that appear to twist the preceding story into a markedly different shape. As Burger himself pointed out when he recently appeared at a Chicago preview screening, this turnaround can also be seen as an invitation to interact: we can accept it as the “true” version of what happened or as Inspector Uhl’s ingenious interpretation. Either way, it’s Giamatti’s highly expressive reaction to what he’s remembering of the preceding plot and how he remembers it that carries the scene.

Burger’s own magic as a storyteller is clear when Uhl sees a complex diagram supposedly explaining how one of Eisenheim’s tricks is done. We think we’re being enlightened, but Burger’s just distracting us from other tricks he and Eisenheim are up to. Whether we wind up believing or disbelieving the psuedo-explanation or the new illusions is secondary to appreciating the grace of them all.