From The Soho News (March 25, 1981). — J.R.

March 10: Permanent Vacation — a punk art film by Jim Jarmusch, with Chris Parker, visible in the Bleecker Street Cinema’s James Agee Room every weekend this month. A semi-promising beginning offers alternately deserted and busy city streets (crisply shot by Tom DiCillo), and a skinny existential drifter reflecting on the “newness” of rooms in his travels that fades away, replaced each time by dread: “The story is how I got from there to here — or maybe I should say here to here.”

The problem is, while trekking dutifully through enough architectural (and cultural) rubble to furnish at least a dozen other art movies, the movie mainly gets from there to nowhere, at a fairly leisurely crawl. Along the way are a few good ideas and jokes, most of them literary and underdeveloped (like affectless Beckett/beat conceits which evoke Wurlitzer’s Nog), one of them actorly (Frankie Faison), some of them musical (John Lurie of the Lounge Lizards). Chances are, if this is the sort of thing you like, you’ve already found your way there.

March 11: Marta Meszaros’ Nine Months, a Hungarian feature made in color five years ago, now on at the Cinema Studio 2. If yesterday’s art film suggested the more content-laden, Woody Allen side of Antonioni, this beautifully shot love story has an extraordinary amount of placeness that helps to compensate for the tinny drone of the theme music. (Why do so many sensitive Eastern European films have scores that remind one of ski lifts?) The camera takes possession of unexceptional industrial landscapes in a way that ensures we remember them like places we know (cf. the courtyard in Tree of the Wooden Clogs.)

The characters also tend to improve with familiarity. Juli (Lili Monori), the strong-willed independent heroine, starts out fairly unattractive — a bit bovine, her face a frozen, freckled sneer (though without the mashed-potato expression of an Isabelle Huppert) — and then, thanks to an inventive performance, steadily grows in character. The fucking and eating in this movie (which turns beds and dishes into memorable places, too, and are sometimes mixed à la Oshima’s In the Realm of the Senses) are as attractively tactile as the natural light and the climactic childbirth.

March 12: I finally catch up with Polanski’s Tess, at the Little Carnegie. Another persecuted unwed mother like yesterday’s Juli; more lushly felt landscapes, decked out in this case with Dolby environmental trimmings. Why do the reproduction and amplification of old Hollywood literary-adaptation techniques (with additional pages from Lean and Kubrick) conspire to make an art film of the late 70s? The delayed American release seems characteristic of a period in which most art films identified with prestige and money — Apocalypse Now, The Deer Hunter, The Elephant Man, Kagemusha, late Woody Allen, and Raging Bull — are Pyramid-like monuments to masculine self-pity, while the European releases are mainly restricted to movies that make the middle class look chic.

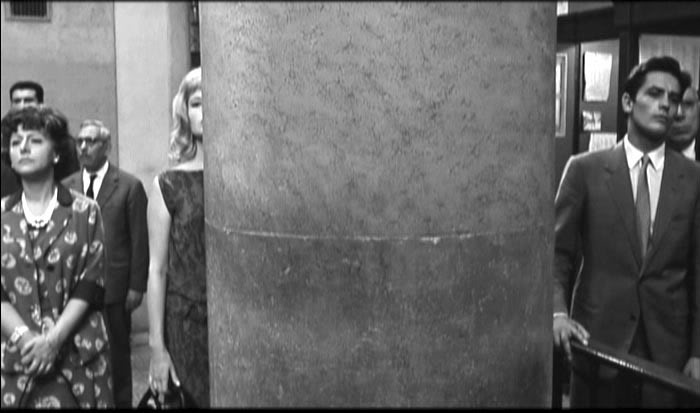

March 13: A movement from the sublime to the ridiculous today: showing Antonioni’s remarkable Eclipse (1962) in my Contemporary Cinema course at NYU, then rushing uptown to attend a press show of Bob Rafelson’s silly male-weepie remake of The Postman Always Rings Twice….What a pity that the literary defenders of Antonioni in the early 60s — presumably Woody Allen’s mentors — took to the alienation cliches and literary metaphors of Eclipse like kittens to milk, even while they were criticizing them (“Macdonald’s taste for kitsch is largely negative, but it is genuine,” wrote Harold Rosenberg), and ignored the richer exuberance of the better parts (like the Stock Market scenes, which deftly juggle documentary and choreography in the mise en scène).

Postman, the only genuinely ludicrous art movie I see for this column, is the one that most people are likely to rush off to; I know a media blitz when I see one, and what fools we mortals be. Yet despite some respect for the hard, serious work of Jessica Lange — who seems to bear the same talented relation to Tuesday Weld that Paul Newman once had to Brando — I can’t take more than a minute or two of Rafelson’s rich-boy macho fantasies about how the sweaty lower classes are supposed to behave (already painfully evident in Five Easy Pieces and Stay Hungry) without starting to snicker at all those carefully applied grease stains and creases in Jack Nicholson’s monkey suits. (In the grip of boredom, to paraphrase the ad campaign, two things can happen — the second is laughter.)

Apart from offering an insult to everyone in America who’s ever worked in a filling station, Postman lacks any coherent sense of character or place. What one gets instead is a glitzy post-Kazan melodramatic score and a pushy use of period detail, from Nicholson’s gaudy duds (he dunks, too) to oil signs to magazine covers. Describing the supposedly steamy “kitchen fuck,” which boldly offers flour to rival the butter of Last Tango and the jam of The Night Porter, a critic in the current Film Comment notes that “a very explicit move to her groin, with her hand ordering his, seems to indicate the paramount urgency of her orgasm”; if he’d spelt that “Paramount,” I’d have understood in a flash. Otherwise, Postman hasn’t much point beyond the dumb-brute arrogance of its money, which unfortunately has more clout in this world than taste, intelligence, or talent.

***

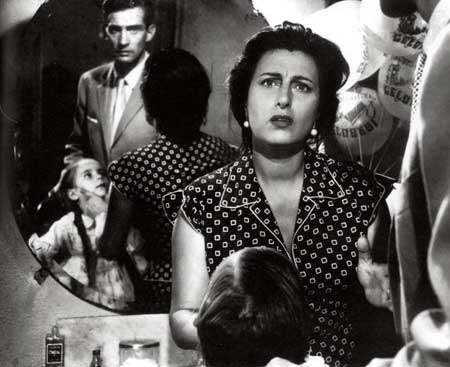

March 17: One very agreeable way of obliterating all recollection of Postman might be to catch the dynamite double-bill at the Public that’s on through the 29th, and then from the 31st through April 5. Visconti’s Bellissima (1951) and Antonioni’s The Lady Without Camelias (1953) are both neglected movies which satirize popular Italian filmmaking, and each is a flawed yet fascinating “early” work by a master who started late. (Antonioni’s third feature was made when he was 41, Visconti’s when he was 45.) They are probably the closest that either director has come to comedy.