Commissioned (but never published) by the Guardian, circa 2005. A much-expanded version of this wound up as the final chapter in my book Discovering Orson Welles. — J.R.

When Will — and How Can — We Finish Orson Welles’s Don Quixote?

When Orson Welles died in 1985, he left many of his films unfinished. Each one was unfinished in a different way and for somewhat different reasons. To the despair of anyone who has ever tried to market his work, no two Welles films are ever alike, even the theoretical ones.

But his Don Quixote, which he owned himself, is distinct from the others, for a number of reasons —- apart from the fact that something calling itself the Don Quixote of Orson Welles was put together in 1992 by Spanish hack director Jesus Franco, who did more to mutilate and distort Welles’ material than anyone had ever done to The Magnificent Ambersons or Mr. Arkadin.

It remained an active project for almost the last three decades of Welles’ life. Starting around the early 70s, Welles jokingly planned to call it When Will You Finish Don Quixote? And the question we used to ask Welles we now have to ask ourselves — namely, how can we find closure? But maybe we should be asking ourselves instead, should we find closure? For I would argue that, more than any other Welles project, Don Quixote remained unfinished by choice.

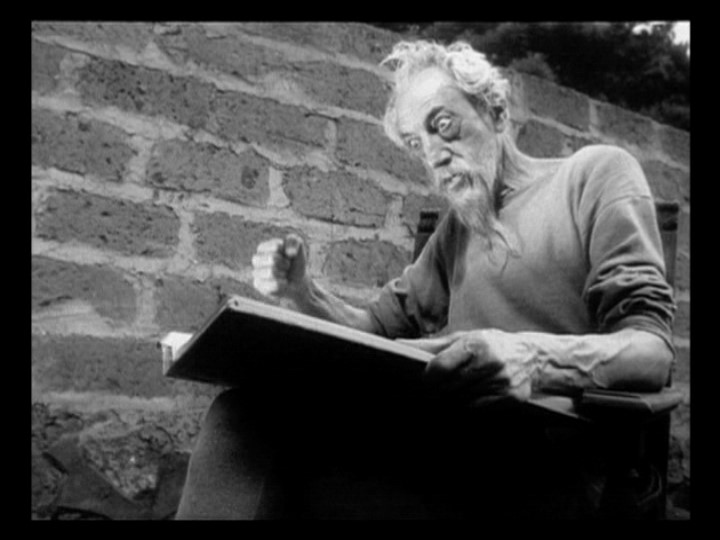

There were at least four successive versions prior to the Franco mess: (1) Tests shot in Paris with Mischa Auer as Quixote and Akim Tamiroff as Sancho Panza. (2) Mexican footage with Patty McCormack, Tamiroff, and the substitution of Francisco Reiguera for Auer. (3) Footage shot in Italy and Spain, when Welles was still, at least initially, hoping to retain the McCormack footage by using a double for her. And (4) an essay film about the paralysis of Spanish culture under Franco, which would raise the philosophical question of whether democracy would destroy the Man of La Mancha.

The versions Welles worked on the longest were the second and third. My favorite is the second; Welles’s inability to finish this version due to depleted funds left him in tears on his last day of shooting. (Ironically, the parts shot in Spain were hampered by the absence of Reiguera, who couldn’t enter the country due to his anti-Franco past.) The Mexican material with McCormack provided the film’s original narrative framework –Welles recounting the story to a little girl named Dulcie (to recall if not duplicate Dulcinea), who then encounters Quixote and Panza on her own. Oja Kodar — Welles’ mistress and collaborator, who inherited the footage, and recalled Welles’ own instructions to her — didn’t allow Jesus Franco to use this material. But to replace it, Franco took footage from Welles’ 1964 Italian TV documentary series Nella Terra di Don Chisciotte — amiable hackwork, done in the form of home movies, in order to bankroll Quixote’s Spanish footage — with disastrous results.

There are many references to Cervantes’ novel and its leading character throughout Welles’ oeuvre. We can also see links between Quixote and Falstaff in Welles’ Chimes at Midnight (which he made in Spain) that relate to the fact that Cervantes and Shakespeare were contemporaries. Nostalgia is one of the most powerful emotions in Welles’ work, mainly expressed for two historical periods — for the middle ages from the vantage point of the late 16th and early 17th centuries, which we find in Chimes and Quixote, and for the late 19th century from the vantage point of the 20th, which we find in Citizen Kane, The Magnificent Ambersons, Moby-Dick (which Welles adapted in one of his major stage productions), and the tales of Isak Dinesen (which formed the basis for The Immortal Story and The Dreamers, another unfinished project). In Welles’ version of Quixote — with Quixote and Panza in their period garb trekking through the equivalent of contemporary Spain — one could almost say that it’s the 20th century that looks incongruous rather than the age of chivalry.

A curious absence to be found in all the projected versions is virtually all the Cervantes characters, apart from Quixote, Panza, and their respective horse and donkey. We certainly see many crowds, all of them contemporary, of villagers as well as city folk, but hardly any individuals to speak of. I especially miss the curate, the barber, Quixote’s housekeeper, and his niece.

There’s a curious paradox at the heart of Cervantes’ novel involving its two main characters. In very different ways, they’re ineffectual fools: Quixote is well-educated, intelligent, thoughtful, and articulate, but also seriously delusional; Panza has practical intelligence and folk wisdom, but due to his lack of education is constantly tripping over his own language and expressing himself badly. Yet as Harold Bloom points out, “We need to hold in mind as we read Don Quixote that we cannot condescend to the Knight and Sancho, since together they know more than we do.” (It’s very tempting to include both Cervantes and Welles in this “we”.) Bloom continues, “The Knight and Sancho, as the great work closes, know exactly who they are, not so much by their adventures as through their marvelous conversations, be they quarrels or exchanges of insights.”

Welles is certainly attentive to their profound self-knowledge. Yet it’s questionable whether he maintains quite the same balance between these characters’ strengths and weaknesses that Cervantes does. Part of this difference may be attributable to the casting. Akim Tamiroff qualifies in some ways as Welles’s favorite actor as well as one of his best friends, having used him in no less than four features, and his Sancho Panza is his earthiest performance. It’s important to stress that his character’s voice (like Reiguera’s) isn’t his own but Welles’, yet it does seem significant that Welles gives Sancho a coarse American twang to Panza. This corresponds to the aristocratic and populist strains in Welles’ own personality, which all his films synthesize in various ways. It also suggests a fusion of American and European energies that’s more fruitful than the Tower of Babel mixture of American and European accents heard in The Trial.

One remarkable sequence in the Mexican material, which survives without sound, shows Dulcie joined in a crowded cinema audience by Panza, with Quixote seated a few rows ahead. They’re watching a sword and sandal epic, and Quixote suddenly comes to the aid of onscreen maidens by striding up to the screen and slashing away at it. As the rowdy crowd both jeers and eggs him on, he seems impervious, continuing with his thrusts until the screen’s in tatters.

There are many fine scenes in Welles’ free adaptation of the novel, but this one, loosely derived from the destruction of a puppet theatre in Part 2, is the only one I’ve seen that fully captures the original’s tragicomic cruelty. It’s still in the possession of one of the film’s original editors, Mauro Bonnani, and it turned up on Italian TV a few years back. I recently showed this clip in Spain for the first time, to great effect, at a conference devoted to Quixote and cinema.

For those who remain confounded that Welles failed to release his Quixote, his perversity arguably remains defensible from a practical standpoint. He realised that his low-budget lark would have been critically attacked, and the odds of it succeeding at the box office would have been virtually nil. The one time I met him, in 1972, he claimed it was virtually complete apart from some sound effects and music, but he didn’t want it to compete with the film of Man of La Mancha that was due out shortly. Given the harsh comparisons that had already been made between his Macbeth and Othello and Olivier’s Shakespeare films of the same era, this is understandable. On the other hand, continuing to tinker with the film obviously gave him a great deal of joy. I’m even persuaded that he actively took steps to prevent the film from being reassembled correctly after his death, and may have even dismantled one or more versions that he came close to completing.

When will — and how can — we finish Orson Welles’ Don Quixote? Truthfully, we can’t finish it, though we can certainly choose whether or not we want to be finished with it. I choose not to, because I think our imagination — which includes our delusions — is always the most basic tool in Welles’ bottomless bag of tricks, and I’d hate to put it out of work.