I’m not sure why, but it seems like Woodstock has rarely gotten its due as a film. This review for the Chicago Reader ran on August 12, 1994, while I was working in New York on the New York Film Festival’s selection committee, and I recall that as a consequence I had to write and get most of this piece edited in Chicago well in advance. A little bit of it is recycled from the first paragraph of an article that I wrote for Grass: The Paged Experience, the 2001 book spinoff of Ron Mann ‘s documentary Grass — an update and revision of an article I wrote for High Times 15 years earlier. –J.R.

WOODSTOCK **** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Michael Wadleigh

With Richie Havens, Country Joe and the Fish, Joe Cocker, Sha Na Na, Arlo Guthrie, Joan Baez, Ten Years After, Santana, Sly and the Family Stone, Janis Joplin, the Who, John Sebastian, Jefferson Airplane, and Jimi Hendrix.

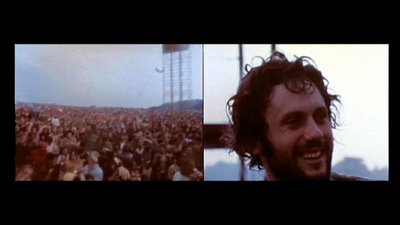

Michael Wadleigh’s epic documentary Woodstock (1970) has been reviewed often as an event, a symbol, and a cause, but it’s seldom been considered strictly as a movie; yet on this score it’s light-years beyond anything on the 60s counterculture ever released by a Hollywood studio. It’s arguably the only commercial release that ever came close to telling it like it was, perhaps because it defines itself less as conventional journalism than as “new journalism” — that is, not as simple description or analysis but as multifaceted experience. Though it remains predominantly an account of a three-day rock festival attended by nearly half a million people, its diverse strategies for marshaling this material are awesome. Split-screen images have been used in many other wide-screen movies, but nowhere else as effectively and inventively; and the sound recording is so good that, by common consensus, the original “sound track” album, released around the same time in 1970, paled beside it. (Unfortunately it’s playing here at the Music Box, whose stereo system won’t do it justice; it seems part of the Hollywood studios’ deranged priorities nowadays that any movie not made this year is automatically an art film — which is why That’s Entertainment! III, the second-best big-studio release to come out this year, got the same venue. And apparently the possibility of showing Woodstock in 70-millimeter locally never occurred to anyone.)

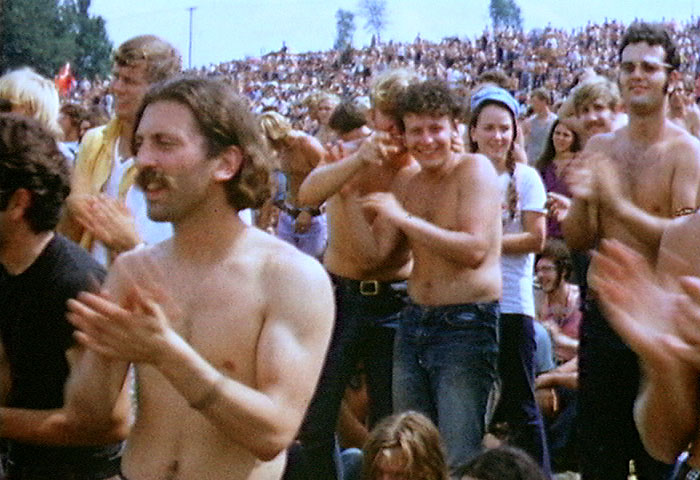

For all Woodstock‘s outward appearance as the simple record of an event, its grand mosaic structure –both overall and in individual sequences, expressed through the editing as well as the split-screen compositions — is both intricate and masterful. The film begins and ends with offscreen music commenting on the festival’s preliminaries and aftermath, and occasionally it cuts from the bandstand to the audience when an illustration of a particular theme is desired — pot smoking for an Arlo Guthrie number, for example, or babies and toddlers for a John Sebastian ballad. But generally it remains focused on the performances — sometimes showing them from two or three angles at once, sometimes juxtaposing or cutting to reaction shots as if these were an integral part of the musical accompaniment. Most impressive is the way these choices never slide into stylistic formula, though the cutting and the introductions of multiple images are always geared to the beat and the developments of the music.

Astonishingly, some normally sensible colleagues of mine claim to prefer Gimme Shelter — a piece of glib pessimism and dishonest reporting whose ideological agenda continues to appeal to those distrustful of Woodstock‘s relatively utopian approach. The official hype back in late 1970, when Gimme Shelter was first released, was that the violent deaths at Altamont exposed the “lie” of Woodstock — as if the “truth” of one event could somehow cancel out the “truth” of another. According to this scenario, the Maysles brothers’ account of a disastrous Rolling Stones concert was enlightened muckraking that countered the hippie propaganda of Woodstock. For viewers who felt intimidated by the quasi-revolutionary political implications of Woodstock, there was something comforting about Jagger’s stylish gloom as he “looked death in the face”. In fact the film’s message that human nature and crowd psychology are vile was every bit as much a media concoction as the sunnier message of Woodstock. As Pauline Kael pointed out at the time, Gimme Shelter was “shaped so as to whitewash the Rolling Stones and the filmmakers for the thoughtless, careless way the concert was arranged, and especially for the cut-rate approach to keeping order.”

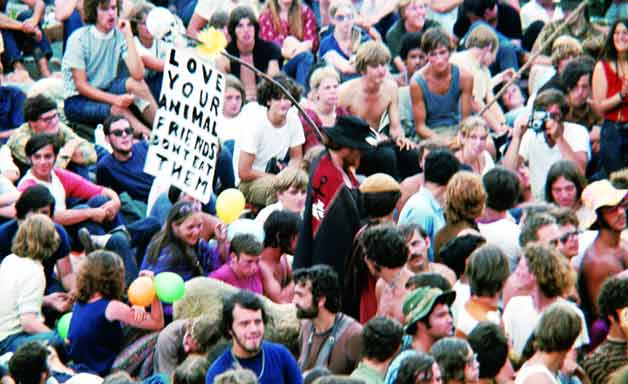

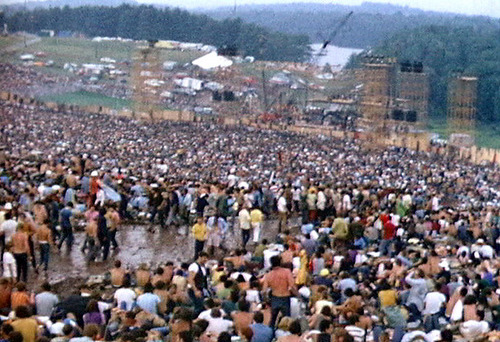

Herbert Marcuse may have had a point when he argued that rock is a tool of the establishment, but it’s worth adding that Woodstock was a lot more than a rock concert. Overwhelming its planners as well as its headliners, it became for three days an impromptu city, and attempting to sum it up with a single, unambiguous political meaning would be as foolhardy as trying to categorize any city of almost half a million people — even if nearly all of them did happen to be hippies. Wadleigh chose to emphasize the euphoria over the discomfort and squalor, but he didn’t ignore the downside; even the trash collecting that followed the festival gets an extended sequence of its own.

One could argue that the principal difference made by the 40 minutes added to the “director’s cut” now showing — including new numbers by Canned Heat, Jefferson Airplane, Janis Joplin, and Jimi Hendrix — is that they simply make the movie too long. To my taste, the Canned Heat performance, shot conventionally in single-image ‘Scope, is completely unnecessary, and even the more inventively presented Jefferson Airplane could have been dispensed with. But the Joplin and Hendrix material is an exciting, invaluable addendum.

Yet it’s not as though the extra footage were anything new: it’s been out on video for some time (until it was recently withdrawn by Warner Brothers to make room for the director’s cut). And when I first caught the original at the Cannes film festival in May 1970, before it opened in the United States, director Wadleigh noted that the longer version had already been shown elsewhere — India and Pakistan, if I recall correctly. The only genuine additions I’m aware of are a gag at the beginning tweaking the R rating this movie has been intolerantly assigned (starting things off on just the right note of irreverence) and a roller text at the end that offers an affecting and appropriate historical and political context.

The contradictions of the movie as mass-market propaganda were already apparent at the 1970 Cannes launching. Wadleigh, a hippie himself dressed in suede, dedicated the film to the four students killed by National Guardsmen at Kent State only five days earlier — “and the many deaths to come,” I recall he added. When the screening was over, he stood by the exit and handed a blackarm band to anyone who wanted one. I wore one myself for a day or so, but Warner Brothers was giving out Woodstock buttons at the same time, and after a while it began to seem that the arm bands and the buttons were interchangeable (after all, this was Cannes). Then, as if to prove the point, by the end of the week some boutiques in Cannes started selling black arm bands.

Sad to say, Wadleigh has managed to make only one feature in the quarter of a century since Woodstock: the underrated Wolfen, released in 1981. (Even this, a sort of new-age horror thriller set in New York, wasn’t a project over which he had full control; he was replaced before the end of shooting by an uncredited John Hancock, and many writers were brought in as well.) By all accounts Wadleigh has remained a hippie, which undoubtedly has made him less bankable in post-Reagan Hollywood. My knowledge of his pre-Woodstock career is spotty, but I know that he attended Columbia University’s medical school at one point and that he served as cinematographer on Jim McBride’s first two features, underground independent efforts called David Holzman’s Diary and My Girlfriend’s Wedding. Wadleigh was one of the main cinematographers on Woodstock as well, and perhaps partly responsible for the trippy cinéma-vérité style of much of the camera work. (Martin Scorsese, one should note, was one of the film’s main editors as well as assistant director.)

***

A good example of how the film’s documentary method corresponds to new journalism comes in one of the first onstage stretches, an intense, buoyant performance by Richie Havens. After Havens’s entrance is caught in the left panel of a split-screen frame while the right panel shows some of the stage crew’s last-minute preparations, the full-screen camera is firmly planted in a low-angle close-up of Havens with his guitar as he sits down on a stool, punctuated by rapid pans to his tapping feet and strumming fingers and occasionally tilting to catch his figure in more oblique, gravity-defying angles. In short, the concentration on his isolated figure is total, and the camera’s low vantage point expresses adoration — as if the half million spectators have all been magically pooled in a single lens held by a kneeling cameraman.

When Havens’s second number commences and we hear the offscreen audience rhythmically clapping along, there are brief cutaways to Havens’s two sidemen, but otherwise the camera remains glued to his upper torso and guitar, with occasional zooms up to his face. When he sings the line “clap your hands,” however, the camera cuts first to a widening vista of thousands of clapping spectators, then to a much less populated view of the back of the bandstand, where nothing of any visible consequence is happening: there’s no clapping, no watching or listening — just a few figures milling about near the stage or on the hill behind it. When the camera returns to Havens he’s in profile, then there’s a cut to a close-up of his conga drummer before the final shots of Havens stepping back reveal both his sideman and his audience in the frame with him as he triumphantly leaves the stage.

The editing in most of this sequence certainly maintains a dramatic logic: the major elements of the event are introduced, then integrated like building blocks. That seemingly illogical cut to the back of the bandstand is different, but it corresponds precisely to the sudden shifts of orientation and perspective of a marijuana high. The quick movement from total concentration to Zen-like disassociation is perhaps the key pot experience, and the camera work and editing in Woodstock underline that mode of perception. Yet the film never succumbs to incoherence or chaos because it always respects the larger structures of sequences; it’s as if Zen and the Art of Archery had served as the film’s style manual. By contrast, the films made by Frank Zappa during the 70s, whether psychedelic in inspiration or not, tend to collapse into incoherence because they fail to respect the larger, more conventional structures of filmmaking, as do most of the other “free form” independent rock movies of the period. Only Woodstock was hip enough to draw on such distancing devices without being overwhelmed by them.

***

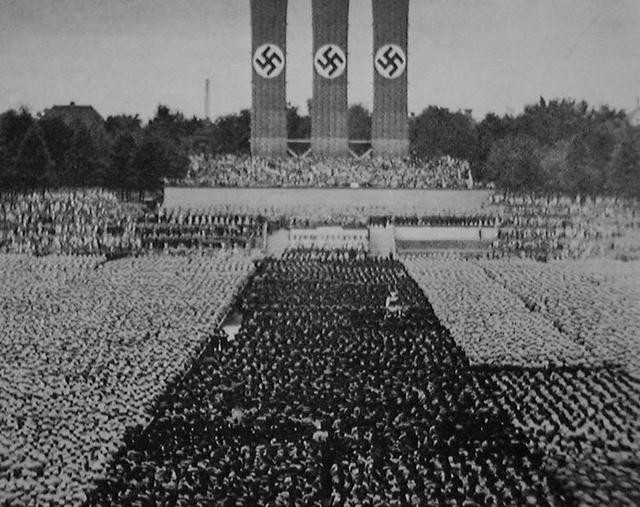

As a consequence of Woodstock‘s overall epic shape, its teeming crowds, its awestruck euphoria, its adoring low angles of charismatic performers, and the fact that it was a film record of an event planned in part for the purpose of making a film, I decided back in 1970 that it was really the counterculture’s equivalent to Leni Riefenstahl’s Triumph of the Will, and mentioned this in print several times during the 70s and 80s. (The fact that Wolfen‘s view of wolves as superior beings corresponds to certain aspects of Riefenstahl’s 1945 feature Tiefland only enhanced the parallel.) But ironically, after noticing recently that many of my colleagues have reached the same conclusion, I’ve been prompted to rethink the accuracy and justice of this comparison.

It’s true that, as historical documents, Triumph of the Will and Woodstock both have the value of imparting to viewers today just what it was that was so appealing to millions of people about Nazism and the 60s counterculture respectively. But it’s questionable whether placing Nazism and 60s counterculture on the same plane clarifies more than it distorts and obfuscates them; the only contemporary public arena in which such an equivalence could be established would be the TV sitcom, such as Nazism on Hogan’s Heroes and 60s counterculture on All in the Family. In short this kind of equivalence is predicated on the Forrest Gump view of 20th-century history, which is pernicious because it reduces complex cultural movements to the level of sound bites and punch lines.

Such a comparison leaves too many crucial factors out — including the salient fact that Woodstock is a vastly more entertaining picture. Furthermore, as propaganda Woodstock is nowhere near as uninflected and monolithic as Triumph of the Will; antihippie sentiments are given full expression in the former, but one hears not a peep of anti-Nazi sentiment in the latter. Woodstock is sufficiently open-minded to include the paranoid freak ranting during a rainstorm that “fascist pigs” have been seeding the clouds, while none of the less seemly activities of Nazis (such as their massive exterminations of Jews, homosexuals, Gypsies, and others) is allowed any expression in Triumph.

Not having attended the 1969 Woodstock festival, I can’t comment on how completely or accurately it was captured in this film. But no less a filmmaker than King Vidor expressed how much he envied Wadleigh for the drama and spectacle of the rainstorm sequence — a glorious stretch culminating in split-screen depictions of the spontaneous mud sliding, percussion playing, and dancing in the storm’s wake. Indeed, if one were to look for Woodstock‘s film antecedents, it might not be farfetched to cite some of the late silent films by Vidor and others dealing with the multiplicity and energy of urban crowds — films like Vidor’s The Crowd, Paul Fejos’s Lonesome, F.W. Murnau’s Sunrise, Walter Ruttmann’s Berlin, Symphony of a City, and Dziga Vertov’s The Man With a Movie Camera. Their superimpositions, split-screen framing, diverse forms of editing, and rhythmical handling of crowds are in many ways comparable to Wadleigh’s strategies. The fact that his “city” was some 400,000 young people camped out in a New York pasture is less important than the strategies he and his able team used — such as the double-screen sequence showing kids lining up to phone their parents.

I haven’t said much about the musical performances, which for many people today will be the main reason to see the show. But even for someone like me, who is something less than a diehard fan of most of the musicians involved, there are still plenty of hair-raising moments. (Three of my favorites: Sha Na Na’s deliriously choreographed “At the Hop,” Ten Years After’s volcanic, driving “I’m Goin’ Home,” and Jimi Hendrix’s apocalyptic rendition of “The Star Spangled Banner.”) And to be perfectly honest there are a few dull patches: for all her political dignity and freshwater voice, Joan Baez singing “Joe Hill” and “Swing Low, Sweet Chariot” seems as dull to me today as it did in 1970. But a masterpiece like Woodstock can accommodate such lapses. Submitting to its exhilaration one realizes, with relief, that despite the media’s dogged efforts to bury everything about the 60s that was worth caring about, this movie has preserved some of it and shown what some of it meant. If you want to know why it was a good time to be alive, here’s the place to go.