Written for the BFI DVD release of The Gold Diggers in 2009. — J.R.

A quarter of a century after its initial unfriendly reception, it’s worth puzzling over why a film as beautiful, as witty, as imaginative, and as brilliant as Sally Potter’s first feature could have given so much offense to certain spectators in 1983. The recoil was so unforgiving in some quarters that Potter, after touring extensively with the film, came to seriously question it herself — or at least the wisdom of having made it, insofar as it was already threatening to end her ambitious career in filmmaking almost before it had properly started, thereby eventually persuading her to withdraw the film from circulation. (By contrast, the exceptional success of her 34-minute Thriller in 1979, an unpacking of Puccini’s La Bohème, made with many of the same collaborators — most notably Colette Laffont, Lindsay Cooper, and Rose English — had clearly heightened her expectations.) Now that it’s belatedly becoming available again on DVD, it’s more than entitled to a fresh look — including a consideration of what originally perturbed some people about it.

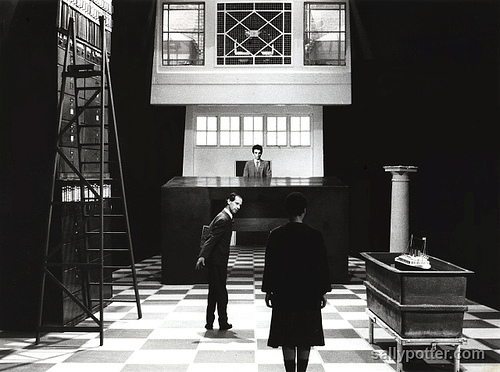

Even after one totes up all of the most obvious of the possible objections that could be raised against The Gold Diggers — boredom, anti-feminist backlash, envy of other independent filmmakers for Potter’s lavish funding from the National Film Board, pretentiousness, allegorical and metaphorical density, sheer difficulty (as Ruby Rich, a sympathetic analyst, put it in her 1998 book Chick Flicks, `Its commitment to narrative [is] minor’) — the inability or refusal of many viewers to grasp or even notice The Gold Diggers’ no less obvious and unassailable strengths continues to confound me. Just for starters, there are the gorgeous images by one of the world’s greatest cinematographers, Babette Mangolte — clearly her best work in black and white, as Mangolte has often maintained herself, and perhaps her most impressive work altogether. From the awesome opening pan across an epic Icelandic landscape, which suggests an etching or a woodcut almost as much as photography, the brilliance of Mangolte’s high-contrast palette and its surrealist impact (which nowadays one would be more apt to call ‘Lynchian,’ and compare to Lynch’s own first feature, Eraserhead, as well as its Victorian and equally neotheatrical follow-up, The Elephant Man), defying the chestnut about black and white being more ‘realistic’ than colour, already makes this movie an extraordinary achievement. As in Orson Welles’ The Trial, the film creates an imaginary geography, multinational and labyrinthine, in which interiors and exteriors, locations and sets, and onstage and offstage spaces are often difficult to disentangle.

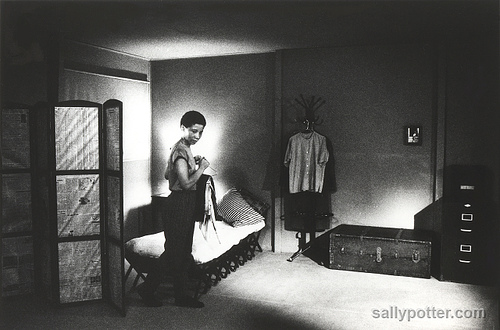

And even if one chooses to discount or ignore the historical (albeit extra-textual) precedent of Potter hiring an all-woman crew, what about the grace and beauty of Julie Christie? The indelibly haunting and throbbing bassoon-heavy score by Lindsay Cooper, one of the film’s three screenwriters? The bold, imaginative, and sometimes disturbing oversized sets by art director and costume designer Rose English, another one of the screenwriters? And what about the witty and pungent cross-referencing of film history by Potter herself (the third screenwriter) — making The Gold Diggers perhaps the only English feature that truly qualifies as Godardian, working out of a critical canon that’s no less eclectic and wide-ranging?

Of course the opening offscreen monologue (‘I’m born in the light and move continuously, yet I’m still’) is also about cinema, and this ontological rumination ultimately informs everything else that the film chooses to consider — the `movement’ of gold and money and blood, the exchange value of women, and the delight of breaking free from the usual habits and practices.

Like Elaine May’s mainstream disaster Ishtar a few years later, I think that some of the outrage ignited by The Gold Diggers, unacknowledged and no doubt often unconscious, must have been ideological — a kind of transgression in Potter’s case that had a certain relation to genre as well as gender. While May was castigated mainly (and improbably) for spending too much money, surely some of the bile provoked by Ishtar, despite this writer-director’s clear affection for her dumbbell heroes, was her spot-on exposure of American idiocy in the Middle East, long before the first Gulf war was even a gleam in the eye of George Bush Sr. And I’m sure that at least part of the rage elicited by The Gold Diggers had to do with Potter’s promiscuous cross-breeding of avant-garde and mainstream, gaily mixing together musical, anti-capitalist satire, SF fantasy, Western, quirky lesbian agitprop, silent melodrama, Screen magazine film theory about the male gaze and various kinds of capitalist discourse, period costume adventure, glum allegory, and deadpan farce — along with diverse forms of both modern dance (including tapdance) and landscape art, not to mention a glamorous commercial icon like Christie. And still another (and likely even more furious) part must have come from Potter having deliberately used her stereotypical male characters so marginally and incidentally that they mainly wound up registering as weak, silly, and interchangeable.

“Perhaps [the] determination to laugh in the face of power was what upset those critics more than anything that the film says explicitly,” aptly writes Sophie Mayer in her recent The Cinema of Sally Potter: A Politics of Love, cinching the parallel with Ishtar a bit more precisely. So it seems entirely appropriate that the mocking laughter of Ruby (Christie) towards her former male captors would apparently elude Janet Maslin when she scornfully reviewed the film in the New York Times in 1988, expediently consigning the film’s few overseas defenders to a different planet and implicitly declaring its mise en scène, cinematography, music, and art direction not even worthy of note, much less approval:

`There are critics in Britain who have praised Sally Potter’s Gold Diggers as “witty,” “visually entrancing,” and “an absorbing pleasure,” and there may also be like-minded individuals on the planet Jupiter. But by any reasonable earthly standard, this thing — a 1983 oddity, sort of a feminist, deconstructionist, riddle-filled anti-musical, much of it set on the Icelandic tundra — is pure torture. Its only noteworthy attribute is the presence of Julie Christie, who embodies some sardonic notion of the archetypal, unenlightened movie heroine through the ages. Like it or not, Miss Christie is infinitely better off playing such creatures straight than she is satirizing them here.’

Launching a career bent on both lavish experiment and pleasing an audience, The Gold Diggers failed to perform the way that Potter’s subsequent Orlando did, but this isn’t to say that its own alchemical pleasures aren’t fully available today — as they are in many of her subsequent features (such as my own current second-favourite of Potter’s, Yes.) It’s not enough to say that this first Potter feature, which wears its avant-garde credentials (that is to say, Potter’s own background, in music, dance, and film) unabashedly, skirts pretension. More precisely, it glories in pretentiousness, which in this case basically means a free and highly creative assertiveness about ideas as well as appearances, ranging from its Ubu Roi sense of ritual to its diverse Klondike and gold-rush iconography. It’s a film, in short, that proudly benefits as well as suffers from a surfeit of both significations and giddy percussive patterns, wallowing in excess only because it’s bent on representing and unpacking a few of the excesses already rampant in the world, including cinema. Potter’s savvy as both a film critic and a film historian can readily be gleaned from the films she programmed along with her own at the National Film Theatre in 1983, including among the over two dozen ‘fellow travellers’ of The Gold Diggers such varied yet visibly relevant works as Way Down East, The Smiling Madame Beudet, The Gold Rush, Gold Diggers of 1933, Alexander Nevsky, Dance, Girl, Dance, Hellzapoppin’, Queen Christina, The Red Shoes, The Trial, Persona, Doctor Zhivago, Lives of Performers, The State of Things, and The Power of Emotions. For me, perhaps the most conspicuous omissions here are Dura Lex/By the Law and The 5,000 Fingers of Dr. T. But then of course you can’t always have everything, even if you take the kind of pleasure that The Gold Digger does — and the kind of immoderate pleasure it offers — in trying.