This appeared in the May 28, 2004 issue of Chicago Reader. Coffee and Cigarettes, incidentally, proved to be one of the surprise hits of Jarmusch’s career — not as commercially successful as the subsequent Broken Flowers (though I prefer it to that), but more popular than anticipated. The overhead shots of expresso cups in a more recent Jamusch feature, The Limits of Control, recall those in Coffee and Cigarettes — providing even more of a contrast with some of the weird, transgressive, and uncharacteristic camera angles in the more recent film, starting with the very first shot. (Note: the first photograph below is by Jean-Daniel Beley, who has requested a credit.)—J.R.

Coffee and Cigarettes

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Jim Jarmusch

With Roberto Benigni, Steven Wright, Joie Lee, Cinqué Lee, Steve Buscemi, Iggy Pop, Tom Waits, Joe Rigano, Vinny Vella, Vinny Vella Jr., Renee French, E.J. Rodriguez, Alex Descas, Isaach de Bankolé, Cate Blanchett, Jack White, Meg White, Alfred Molina, Steve Coogan, GZA, RZA, Bill Murray, Bill Rice, and Taylor Mead.

At first Jim Jarmusch’s Coffee and Cigarettes, made over a span of 17 years, looks like a departure for him. It consists of 11 entertaining, mainly comic short films in black and white that show people mainly sitting around in coffeehouses mainly drinking coffee, mainly smoking cigarettes, and mainly talking. But four of Jarmusch’s seven previous fiction features were built out of similarly isolated episodes, and the remaining three—Permanent Vacation (1980), Dead Man (1995), and Ghost Dog: The Way of the Samurai (1999)—are all episodic. Stranger Than Paradise (1984) and Down by Law (1986)—also in black and white—each concentrated on three characters seen in three separate settings. Mystery Train (1989) had three separate sets of characters and three episodes set during the same day in Memphis. Night on Earth (1991)—focusing, like Coffee and Cigarettes, on what might be called downtime—had five separate episodes featuring cabdrivers and their passengers, occurring simultaneously across the globe.

The short form looks like a genuine alternative in Jarmusch’s hands because of what he does with it. He’s a master of minimalism, and his close attention to the form contrasts sharply with the isolated and detachable sequences that have become the calling card of film technique, the be-all and end-all of movie art. The fondness for fragments can be traced back largely to Sergei Eisenstein in the 20s, when famous set pieces began to define the “art of cinema” in many minds—the Odessa steps sequence in Potemkin (1925), the bridge-raising sequence in October (1927), and the cream-separator sequence in The General Line (1929), all eventually supplanted by the shower-murder sequence in Alfred Hitchcock’s Psycho (1960). This tendency was further institutionalized by popular magazines such as Premiere and by countless “the making of” TV documentaries, which applauded the notion of separating sequences from their contexts.

The fragmentation of narrative form in current movies encourages the disassociation of the parts of a film. This may be fine when putting together a trailer, presenting a clip on a TV show, or making a point in a film class, but it undermines any sense of classical proportion or harmony. Few people would call Jarmusch a classicist, yet his fiction features show a concern for these qualities that isn’t shared by many of his contemporaries.

A few critics have shrugged off Coffee and Cigarettes as slight and inconsequential, calling it an exercise in style, done in Jarmusch’s usual “hip” idiom. But I think its form and content are much more notable and consequential than its style.

The film is certainly less ambitious than Dead Man or Ghost Dog, though it’s by no means less personal. The main themes are the ethics of celebrity, the tensions and irritations that can arise between close friends and family members, and two Jarmusch standbys, shyness and loneliness. These themes and the recurring formal elements—ranging from inserted overhead shots of coffee cups and checkerboard tablecloths or tabletops to abstract patterns in the dramaturgy—give Coffee and Cigarettes an overall artistic coherence that’s far from common in current movies.

Having known Jarmusch for over two decades, I think his celebrity status—he can’t walk down the street in many cities around the world without being recognized—is something he both likes and dislikes. He loves the attention, but he’s bothered by the inequities that arise from stardom. A lot of this movie is given over to some very funny observations and ethical reflections on that subject. In the segment titled “Cousins” we see Cate Blanchett playing in the same shots herself during a movie junket and her fictional punk cousin Shelly, who’s seething with jealousy and resentment when Cate meets her in the lobby of her luxury hotel. It’s a technical tour de force, flawlessly executed by Blanchett, Jarmusch, and his crew. I’ve heard that when Jarmusch posed for publicity photos during the shooting of this sequence he chose to be photographed with Shelly rather than Cate, a telling indication of whom he feels more allied with.

Twenty-one of the 27 actors play some version of themselves with the same name, and most of these actors are at least minor celebrities. (For the record, the six who don’t play themselves are Joie Lee, Cinqué Lee in two separate parts, Blanchett when she’s Shelly, Steve Buscemi, E.J. Rodriguez, and Mike Hogan.)

The project started when Jarmusch was invited to contribute a comedy sketch to Saturday Night Live in 1986, shortly after shooting Down by Law, and he cast one of that film’s three stars, the then relatively unknown Roberto Benigni, along with stand-up comic Steven Wright. He shot the film’s second sketch in Memphis (where he was shooting Mystery Train) three years later, and the third one four years after that. The remaining eight were all shot recently over a relatively brief period, meaning that Jarmusch had had plenty of time to plan these episodes individually and develop them as an ensemble, letting them echo and interact with one another and build a whole that’s much greater than the sum of its parts. In this respect Coffee and Cigarettes resembles a cumulative, organically interrelated short story collection such as James Joyce’s Dubliners, Sherwood Anderson’s Winesburg, Ohio, Ernest Hemingway’s In Our Time, or Ray Bradbury’s The Martian Chronicles, rather than an assortment of loose pieces rattling around inside a common container, such as Bradbury’s The Illustrated Man, Nelson Algren’s The Neon Wilderness, Flannery O’Connor’s Everything That Rises Must Converge, or Thomas Pynchon’s Slow Learner.

One of the more mysterious aspects of Coffee and Cigarettes is whether the form creates the content or the content suggests the form. A good example of what I mean can be found in one of the most provocative, though not best-known, stories of Franz Kafka, “Blumfeld, an Elderly Bachelor.” The first part of the story recounts a comic fantasy: the grumpy title hero comes home to his sixth-floor walk-up, and “two small white celluloid balls with blue stripes” begin playfully following him around the room, coordinating their moves with his and with each other’s. They bounce after him for the remainder of the evening, then resume their teasing play in the morning—until he lures them into his wardrobe and locks them inside. The second half of the story prosaically recounts his dull morning at the linen factory where he works, dominated by his irritation with the two assistants who share his tiny office. This story is remarkable not just for the fantasy that precedes the depiction of everyday normality, but for the playful form itself—the subtle and disquieting rhyming of the bouncing balls and the two assistants. One wonders whether Kafka’s concept began with the bouncing balls, the assistants, or the echoes between the two.

There’s a similar ambiguity in Jarmusch’s playful two-part inventions. His second episode, “Twins,” features Joie and Cinqué Lee, two of Spike Lee’s siblings, playing twins (which they’re not in real life); their petty bickering consists mainly of each contradicting and echoing the other. Their dialogue with a waiter (Buscemi) concerns the legendary twin of Elvis Presley who died at birth and the siblings’ charge that Elvis ripped off the music of black musicians such as Otis Blackwell and Junior Parker (another form of duplication).

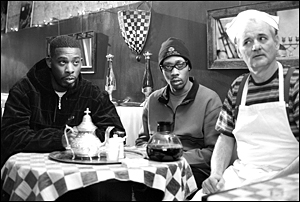

Five episodes later we get “Cousins” (one of my three favorite episodes), followed by “Jack Shows Meg His Tesla Coil,” which features musicians Jack and Meg White, a former couple who pose as siblings. Then we get the hilarious “Cousins?” (one of my other favorites), in which Alfred Molina and British TV star Steve Coogan meet for tea in an LA restaurant, and Molina, hoping to establish some intimacy with Coogan, says he recently discovered that they’re cousins. (In more ways than one, this is the most brilliant episode in the movie–an acute examination of showbiz and celebrity pecking order.) And in the episode after that, “Delirium,” GZA and RZA, members of the Wu-Tang Clan, introduce themselves to Bill Murray as cousins.

Did Jarmusch think first of using twins, siblings, and cousins, or did he start off aiming for rhyme effects? I’m not sure it matters, but the pairings and doublings don’t stop. Many lines of dialogue recur, and the movie opens and closes with separate versions of “Louie Louie” (whose title is already a repetition). The sixth episode, “No Problem,” begins and ends with Alex Descas taking a pair of dice from his pocket and rolling them three times; the results we see are all doubles. The ninth and tenth episodes both have two characters who order tea instead of coffee.

That Jarmusch’s film registers as loose and offhanded despite so much formal control is one of the characteristic achievements of his minimalism. As in Eugen Herrigel’s book Zen in the Art of Archery, he doesn’t appear to care whether he hits the target, though he seldom misses. The only episode that strikes me as being undernourished is the fifth, “Renee,” which lingers over a young woman (Renee French) smoking and drinking coffee while looking through ads in a gun catalog. She’s interrupted by a waiter (Rodriguez) giving her an unasked-for coffee refill and later trying unsuccessfully to make conversation. Yet even this relatively meager segment manages to repeat some lines of dialogue and some formal elements from other sketches, and by focusing once on a character who prefers solitude to conversation, Jarmusch offers a meaningful contrast to the other episodes.

I assume one reason Jarmusch decided to home in on electricity pioneer and maverick Nikola Tesla (1856-1943) in another offbeat episode is that Tesla represents so many “alternatives”—not just alternating current and an alternative to Thomas Edison, but an alternative, utopian history that encompasses Tesla’s ideas about free electricity, free transportation, and free communications. This also occasions what is probably the most poetic of the movie’s recurring lines: “He perceived the earth as a conductor of acoustical resonance.”

The many self-referential details increase the clubhouse atmosphere, and some of the reviewers who dismiss the film may be responding to this. For example, we get blackouts at the end of each section, as we did in Stranger Than Paradise. In the fourth section—which features Joe Rigano and Vinny Vella, who played aging Italian gangsters in Ghost Dog—there’s a framed photo on the wall of Henry Silva, one of their colleagues in that film. And in the eighth segment, with Jack and Meg White, there’s a framed picture of Lee Marvin; Jarmusch and some of his friends once founded a jokey, semisecret club they called the Sons of Lee Marvin.

Other gags can be traced to allusions of one kind or another. (Two that appear to have been studiously avoided: Jarmusch once played a coffee addict in Alex Cox’s 1987 comic western Straight to Hell, and in Wayne Wang and Paul Auster’s 1995 Blue in the Face he ruminated on what he claimed would be his last cigarette.) Jarmusch has noted in an interview that Tom Waits’s speech to Iggy Pop in the third episode—about having just performed “roadside surgery” by delivering a baby and about combining “music and medicine” in his life—was improvised; when Jarmusch later discovered that RZA was into alternative medicine, he decided to duplicate parts of Waits’s monologue in the episode that focuses on RZA and GZA. This mixture of improvisation and formal patterning justifies Jarmusch’s description of Coffee and Cigarettes as “series of short films disguised as a feature (or maybe vice versa),” as well as his formally pitched remark that the film is photographed “in black (coffee) and white (cigarettes).”

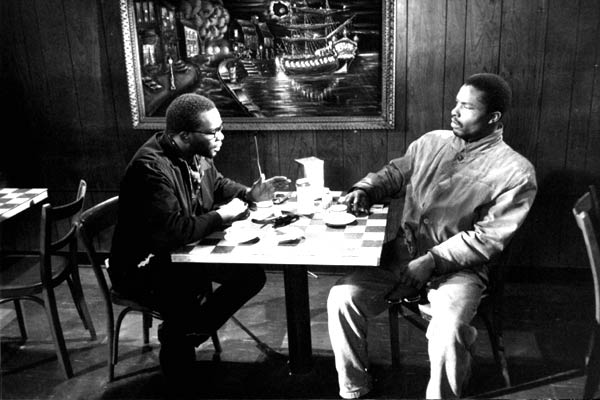

People who object to the in-jokes should consider that they might be just part of a dialectic with what could be termed the out-jokes—the more populist and obvious bits of humor. There’s a close parallel in the dialectic between celebrities and nobodies that runs throughout the film, and there’s the suggestion that inside every apparent improvisation is an element of determination, that juxtaposed with every conspiracy theory is an abyss of meaningless absurdity and chaos, and that next to the political incorrectness of the addictive coffee and cigarettes are politically correct demonstrations of social etiquette. Paradoxically, a certain kind of social chaos becomes most apparent whenever the characters are being most polite: when Isaach (Isaach de Bankolé) meets Alex for coffee at Alex’s request, he can’t believe he’s been summoned just for the pleasure of his company, even though they’re supposed to be best friends. This paranoid misunderstanding is played for comedy, but the fear of a gaping void remains.

The wistful and moving final episode, “Champagne” (my third favorite)—featuring Bill Rice and Taylor Mead in a dimly lit SoHo hangout called the Armory, drinking out of paper cups during their coffee break—seems at first to be at the farthest remove from Jarmusch’s universe, yet it’s a kind of tribute to his roots in the underground filmmaking scene of downtown Manhattan. Rice and Mead are closely associated with those roots through their roles in films by Scott and Beth B., Eric Mitchell, Amos Poe, and Andy Warhol, and they drink a toast at one point not only to “Paris in the 20s” (Mead’s suggestion) but also to “New York in the late 70s” (Rice’s suggestion), which is when these films were being shot.

Certainly there’s no better evocation of chaos in the film than the title of the beautiful Gustav Mahler song heard in this episode, “I Have Lost Track of the World.” The overall abstractness of the location and the absurdist dialogue—including Mead’s when he’s periodically forgetful—call to mind Samuel Beckett’s doleful tramps in their own sketchy settings. Curiously, Rice and Mead seem more settled and “placed” than any other characters in the film, perhaps because they seem older and wiser than everyone else—and perhaps because knowing who you are often entails knowing where you are.