From the Chicago Reader (June 17, 1994). — J.R.

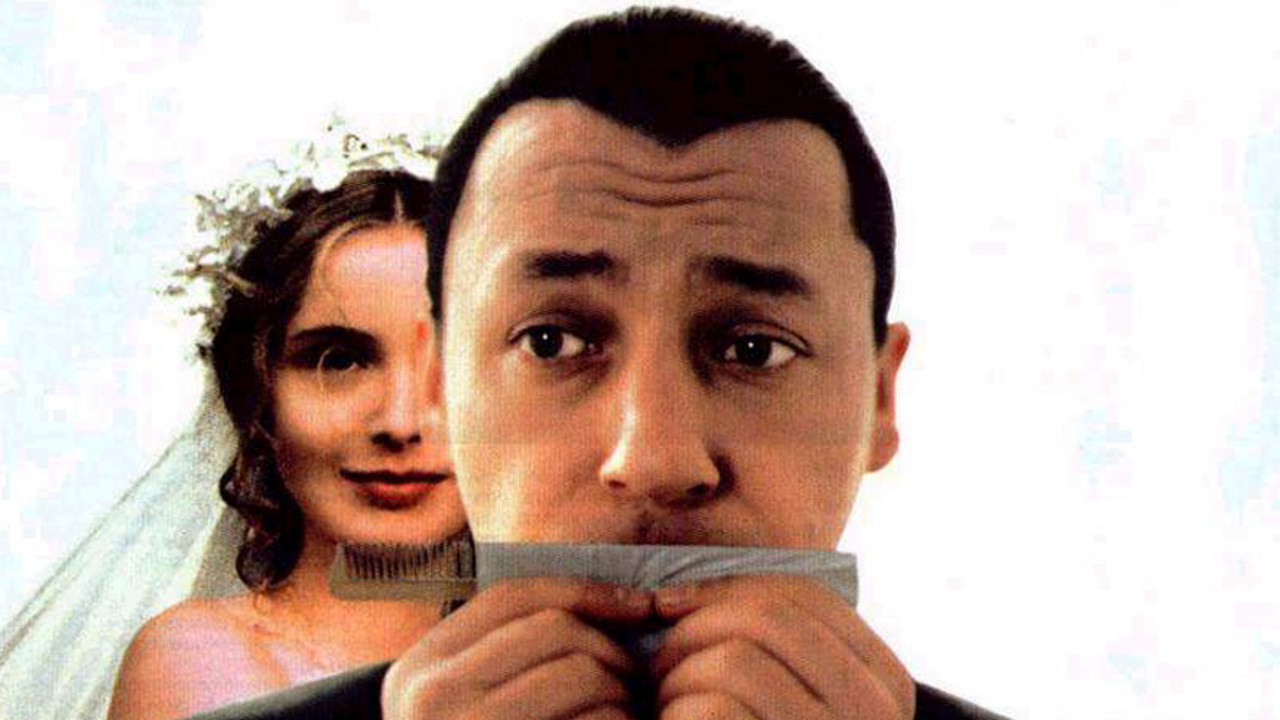

** WHITE

(Worth seeing)

Directed by Krzysztof Kieslowski

Written by Krzysztof Piesiewicz and Kieslowski

With Zbigniew Zamachowski, Julie Delphy, Janusz Gajos, Jerzy Stuhr, Grzegorz Warchol, and Jerzy Nowak.

“Imagine a kind of filmmaking that’s truly in tune with the ways you think and relate to other people. A deeply humane kind of filmmaking, but free from ‘humanist’ lies and sentimental evasions. Not a dry, ‘realistic’ kind of filmmaking, but one in which all the imaginative and creative efforts have gone into understanding the way we are. A kind of filmmaking as sensitive to silence as to speech, and alert to the kind of meanings we prefer to hide away. To my knowledge, only two directors in the world are currently making films like that. One is Krzysztof Kieslowski in Poland. The other is Edward Yang in Taiwan.”

These rousing words by Tony Rayns in the June issue of Sight and Sound were just what I needed to read after returning last month from Cannes, where wonderful films by Yang and Kieslowski about contemporary life were showing in competition. They were the two best competing films that I saw, though neither won any prizes. Yang’s A Confucian Confusion — an intricate, beautifully shot dissection of the new capitalism and nouveau riche of Taipei and the conspiratorial mutual deceptions brought into play by the new economics may be the first truly political film to have emerged from the Taiwanese New Wave, and perhaps even the truest picture offered in Cannes of where the planet is headed. But it made most of the international press, apart from a few aficionados of Asian cinema, uneasy; they were confounded by the complicated plot and overflowing cast of characters, and in some cases directly repelled by the frank exposures of childish macho bluster and hollow consumerist excess that reflected so accurately the frantic nonsense of the Cannes festival itself.

Kieslowski’s Red, the crowning work of his “Three Colors” trilogy, met with a very different public response. As far as the international press was concerned, it was the popular favorite. Considering that Kieslowski had already won prizes for Blue and White at Venice and Berlin in the past year and had announced his retirement from directing at Berlin, some people were primed for a triple crown, even if more savvy forecasters were noting that at a festival dominated by the U.S. and France, where Kieslowski is something less than a universal role model — having alienated both the New York Times and Cahiers du Cinema with the mystical vagaries of Blue — the odds of pulling off such a feat were fairly remote. So when the jury headed by Clint Eastwood opted to ignore Red entirely and bestow its top prize on Pulp Fiction, the message being sent out was that irresponsible entertainment was clearly favored over thoughtful art-house fare. Given the atmosphere of the festival as a whole — closer to that of a business convention than of a cultural event — this was hardly surprising.

Back in Chicago, after reading Tony Rayns in Sight and Sound, I went to see White with the highest expectations, though regretting I hadn’t seen it before I saw Red. My expectations weren’t entirely dashed — technically and stylistically Kieslowski is one of the most accomplished filmmakers around — but they were sufficiently dampened to make me go back a second time to see if I’d missed something. Is White really as glib and as simpleminded in conception as it initially appears to be? After two viewings, I’m inclined to say that it is.

It may be, as Rayns points out, “as sensitive to silence as to speech, and alert to the kind of meanings we prefer to hide away.” It may be that all its “imaginative and creative efforts have gone into understanding the way we are,” but if they have, not much has been understood. And far from being “free from ‘humanist’ lies and sentimental evasions,” White depends on just such lies and evasions to arrive at the limited understanding it does have.

One explanation for the widespread French hostility toward Kieslowski can be indirectly gleaned from the fact that Bruce Williamson concludes his short review of White in the July Playboy by calling it “quintessentially French.” Kieslowski is outspoken about regarding himself as Polish rather than European and has generally been disdainful of French life and culture (including French cinema) — barely speaking the language, even though he’s been largely dependent on French state grants since The Double Life of Veronique. So it’s easy enough to see how some French critics might regard him as something of a carpetbagger, especially when reviewers like Williamson regard an Eastern European allegory like White, set mainly in Poland, as “quintessentially French.” The fact that the “Three Colors” trilogy is based on the colors of the French flag and is avowedly devoted to exploring ironically the contemporary meanings of the ideals of the French revolution — liberty, equality, and fraternity — and the fact that Blue and the first part of White are set in France undoubtedly only adds fuel to their anger, at the same time that it confuses some American reviewers.

If Blue mainly exudes sweetness and Red (which will probably surface here in the fall), set in Geneva, is both sweet and sour, White is clearly the lemon in the bunch, and it’s unmistakably Polish. Its hero, beautifully played by the popular Polish actor Zbigniew Zamachowski, is a Polish hairdresser who barely speaks French, living in Paris when the film opens and making his way to a courthouse where his French wife Dominique (Julie Delphy), another hairdresser, is suing him for divorce after six months of marriage. A pigeon shits on him as he climbs the courthouse steps; inside, Dominique explains that his sexual impotence is her reason for demanding a divorce. He doesn’t deny the charge, but notes that he satisfied her sexually before they were married. He declares that he still loves her; she declares that she no longer loves him. When we next see him he’s vomiting into a toilet bowl.

The hero’s name is Karol Karol; “Karol” is Polish for “Charles,” and Kieslowski has admitted that the character is indirectly modeled on Charlie Chaplin, though Zamachowski’s baby-plump cheeks make him resemble more closely Harry Langdon. A sad sack throughout, he’s presented by Dominique with a trunk containing all his belongings outside the courthouse, and soon afterward discovers that his bank card no longer works. After making one last effort to woo Dominique at her salon, he proves impotent once again. When he then suggests that she return with him to Poland, she flies into a rage and sets fire to the salon, remarking that she intends to phone the police and accuse him of starting the fire as an act of revenge. We next see Karol in a Paris metro station playing a sentimental Polish ditty on a comb, begging for francs, having meanwhile lost his passport.

Still hopelessly smitten with Dominique in spite of her contempt for him, he phones her yet again, and she asks him to hold the phone while she proceeds to have an orgasm with a lover, moaning audibly. By this time Karol has met a fellow Pole named Mikolaj (Janusz Gajos), who quickly befriends him; they concoct a ruse to smuggle Karol back into Poland inside his own trunk. Needless to say, the trunk is stolen in customs and opened in a desolate Warsaw wasteland by a band of Polish thieves, who are so irate that Karol’s carrying only a two-franc coin and a Russian watch that they beat him up. Nevertheless, though surrounded by heaps of garbage, he’s clearly glad to be home.

Before the end of the picture Karol regains his potency, and it’s clear that being back in Poland and making a financial killing in the crass new Polish society, where everything and everyone is for sale, has something to do with his recovery. As a satire about contemporary Poland, this stretch of the movie, most of the 92-minute running time, is sometimes bitterly amusing. But it’s also rather facile, as if Kieslowski decided that once the bare bones of his plot premise were set down, fleshing them out with full characters and close observation was unnecessary. (You need only place White alongside Yang’s A Confucian Confusion to expose its shallowness as a commentary on contemporary capitalism.)

Unfortunately, the same applies to the remainder of the film — to the Parisian prologue — and, most damagingly of all, to the Warsaw denouement: the characters and situations are so doggedly archetypal (rags-to-riches sad-sack hero, bitchy wife, gloomy Polish friend and sidekick, the amoral coarseness of the new Polish society) that one is asked merely to nod in agreement, not to engage with these people and situations. The only exception that comes to mind is Karol’s sweet-tempered brother Jurek (Jerzy Stuhr), with whom he provisionally shares a salon in Warsaw; though Stuhr is every bit as simple a character as the others, he brings a welcome humanity and humor to his part that places him miles away from their cartoonish brittleness.

It might be argued that a comparable sketchiness in overall conception informs the characters and situations of Blue and Red as well. Perhaps this is true, but in those films at least an attentiveness to the everyday fluctuations of the characters’ consciousness, combined with a mystical overview of the action being played out, adds a crucial dimension to the simplicity. In White the only significant passages in which subjective consciousness is apparent relate to Dominique’s fleeting and recurring memories of her wedding ceremony — an overexposed tracking shot up the church aisle, away from the altar toward the open doors and the open air, where whiteness progressively floods the image — and a climactic burst of white that eventually represents her and Karol’s simultaneous orgasm when he overcomes his impotence. Both of these passages are striking and effective, but the characters and emotions they allude to are so perfunctorily established that they can’t make up for the thinness of everything that surrounds them. The audience laughter that greets the climactic white-out orgasm in some ways suggests that this transcendental apotheosis is mainly a punch line in a joke, and not a very good joke at that. Because we’re not allowed to see anything of Karol and Dominique prior to their divorce, apart from the emblematic wedding ceremony, any sense of love regained or a relationship renewed is entirely theoretical.

It’s impossible not to read the plot as an allegory about Kieslowski himself in relation to France and Poland — the impotence of the expatriate artist severed from his homeland — infused with cynical irony about the impossibility of equality in a capitalist society, and the concomitant notion that rapacious aggression in a ruthless postcommunist economy guarantees a sustained hard-on. Rayns has argued plausibly that love in the modern world — rather than liberty, equality, and fraternity — remains the overarching theme of the trilogy. But the love that figures centrally in White — disguised as hate first with Dominique and then Karol — appears more as a postulate than as a realized fact. To achieve something more durable and persuasive, real characters are required, not allegorical stick figures.