From the Chicago Reader (April 5, 1991), and reprinted in Goodbye Cinema, Hello Cinephilia. — J.R.

DEFENDING YOUR LIFE

**** (Masterpiece)

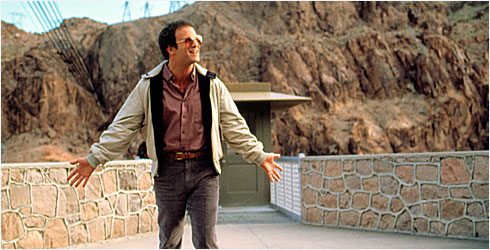

Directed and written by Albert Brooks

With Albert Brooks, Meryl Streep, Rip Torn, Lee Grant, and Buck Henry.

From the very titles of his four comedy features, we know that Albert Brooks is both a serious and an honest filmmaker, because each one is a precise and accurate indication of what the movie is about: Real Life, Modern Romance, Lost in America, and Defending Your Life. But what makes Brooks funny is much harder to get at or agree on.

You can’t demonstrate how funny Albert Brooks is by quoting any of his one-liners, the way you can the vastly more popular and respected Woody Allen. And you can’t say that Brooks is funnier than Allen if you’re measuring by the average number of laughs produced. (I find most of Modern Romance too painfully accurate to laugh at, although the comic conception remains flawless; and even though the laughs come more readily in Brooks’s other pictures, the degree of emotional pain being seriously dealt with is well beyond Allen’s range.) Nevertheless, I think Brooks is the best comic writer-director-actor we have in this country at the moment — certainly the most original and thoughtful, and the one who has the most to tell us about who we are.

At his best, Woody Allen excels at eliciting (and soliciting) surface responses, whether he’s working in comedy or drama. But despite his flair for intellectual name-dropping, fashionable literary themes, and stylishly derivative mise en scenes, none of his movies offers as much genuine and original substance as any of Brooks’s in subject, conception, style, feeling, or execution. Yet Brooks, whose original name was Albert Einstein, doesn’t wear his brain on his sleeve; his intelligence is so integral to his conceptions and their realizations that one can’t reduce it to simple markers — although one could cite his avoidance of close-ups and reaction shots (both Woody staples) and his taste for long takes as emblematic of his more analytical vantage point.

Brooks acknowledges a certain complicity with — as well as distance from — his somewhat obnoxious heroes. Like Woody Allen, as well as such earlier verbally based comics as Jack Benny and Fred Allen, he sculpts his comic vision around his own persona, and partially invites the audience to identify with that persona; he differs most crucially from Woody Allen in the rigorous critical distance he is able to sustain in relation to that identification. While Brooks’s heroes tend to be every bit as regional as Allen’s — as tied to the cultural limitations of southern California as Allen’s heroes are to the cultural limitations of New York — the worlds they inhabit are not at all comparable. When Allen uncharacteristically turns up in Los Angeles in Annie Hall, the city we see is a New Yorker’s Los Angeles; but when Brooks turns up in Phoenix, Arizona, in Real Life or in Las Vegas and less urban parts of the southwest in Lost in America, these areas are not depicted exclusively from a southern California perspective.

In short, Brooks as an artist is able to break away from his roots and see the world outside with some degree of detachment and lucidity, while Allen’s artistry, like his persona, is virtually defined by his inability or disinclination to do that. It’s theoretically possible to imagine and even visualize the comic grotesqueness of one of Brooks’s malcontent heroes actually going to India and working with Mother Teresa; when Allen postulates the heroine of Alice doing precisely that, he simply borrows a clip from a Louis Malle documentary to fill in the blanks. At the very least Brooks would explore the idea; at most Allen can only entertain it.

For all their obvious, fascinating differences, all four of Brooks’s features are contemporary satires, philosophical parables, and highly realistic comedies about self-defeating behavior. And all of them have something to do with the role played by movies in messing up people’s heads and lives. Brooks is the flawed, image-conscious west-coast hero in each one — a filmmaker and comic in Real Life (1979), a film editor in Modern Romance (1981), and advertising executives in Lost in America (1985) and Defending Your Life. Acute self-consciousness is a problem that all four of these heroes either engender or encounter.

Interestingly enough, the brassy show-biz type Brooks plays in Real Life — so close to Brooks’s own public persona that he’s called Albert Brooks in the movie — professes to be impervious to all this. Shooting an extended documentary about the life of a “typical” family in the style of the 1973 PBS series An American Family, he claims that anything the family does in front of the camera is “right,” without admitting that the acute self-consciousness created by his film and camera crew ultimately has more to do with reel life than real life. A related but different sort of obsessive neurosis plagues the self-absorbed editor in Modern Romance, who is consumed by alternating bouts of jealousy and romantic fantasy that make him incapable of either ending or revitalizing a long-term relationship. Like the director, he never seems to know when to leave well enough alone; and while his girlfriend (Kathryn Harrold) ultimately seems as trapped in their unresolved relationship as he is, she’s the main one dealing with the self-consciousness and embarrassment his behavior creates.

The Real Life director ultimately goes berserk when he loses control over both the family being filmed and his picture. By contrast, the Modern Romance editor may act like an infant with his girlfriend, but he never loses his professional cool — which he needs in servicing the demands of the director of a routine, low-budget SF picture (played by James L. Brooks) who is every bit as obsessive about his silly picture as the editor is about his silly relationship. (Both characters are compulsive revisers of mundane, imperfect “material” that seems impossible to redeem, much less improve.)

The yuppie admen played by Brooks in Lost in America and Defending Your Life may seem slightly less demented, but they’re equally victims of impulses that belong to their profession. They’re constantly trying to sell themselves (and others) concepts that might redeem their inadequate lives. Blowing his top and thereby losing his job when he is offered a New York transfer instead of an expected promotion, the hero of Lost in America seizes on his nostalgic 60s memories of Easy Rider and sets out with his wife in a fancy mobile home to rediscover America; acute self-consciousness sets in only when he begins to discover how different his dreams are from the reality he encounters.

Daniel Miller, the blinkered hero of Defending Your Life, loses his life in the precredits sequence by driving his brand-new $39,000 BMW straight into a bus, after being distracted by the CD albums he has just been given as a birthday present. He finds himself in a secular new-age version of purgatory known as Judgment City, a bland, cheerful holiday resort with theme-park trimmings designed especially for recently deceased former inhabitants of the western part of the United States. Daniel gradually discovers that he, like the others, is there to face an examination of his entire life — complete with defender and prosecutor — before he can either proceed to a higher form of existence (if he wins) or return to earth in a fresh reincarnation (if he loses). Only when faced with selected scenes from his life, screened in the form of film clips before a skeletal tribunal, does Daniel acquire the debilitating self-consciousness experienced by Brooks’s other heroes. Around the same time — between the first and second of his four sessions with the tribunal — he meets the recently deceased Julia (Meryl Streep), who has led a far more exemplary life than he has. She is one of the few younger arrivals like him, and the two fall deeply in love.

One can say that each of Brooks’s movies is structured around a key concept — reality (Real Life), romance (Modern Romance), “dropping out” (Lost in America), and fear (Defending Your Life). The ruling principle in Judgment City is that you keep returning to earth in various incarnations until you finally get it right and learn to overcome your fears, at which point you graduate and go on to a higher realm.

We’re told early on that most human beings like Daniel use only about 5 percent of their brains, while those who eventually overcome their fears during their various incarnations on earth — including the Judgment City staffers — use closer to half. We’re also told early on that Judgment City itself is designed to minimize the fears of the recently deceased who are being examined. By extension we can also say that Defending Your Life is designed in order to minimize our fears: this serious examination of the successes and failures of our lives is presented in the form of a lighthearted and fanciful Hollywood cream puff, complete with an improbable happy ending. So the significance of movies in Judgment City isn’t merely that Daniel’s examination takes place in a windowless chamber that resembles a Hollywood screening room — with Daniel seated in a comfortable revolving chair directly in front of the screen, and with occasional beeps given on the sound track at the beginning of film sequences being reviewed (a standard signal in the film industry used for synching up rushes) — but also that Judgment City itself is constructed and experienced like a Hollywood movie.

This general principle even extends to some of Judgment City’s dietary codes: visitors can eat as much as they want without gaining weight. Real people who fill up on popcorn, candy, and pop at the movies obviously gain weight as a result, though many of them are more careful about their diets in the world outside; part of the attraction of movies — and the obvious selling point behind concession counters — is that they encourage one to suspend the usual rules and restrictions that pertain in “normal” life.

A few stray aspects of Defending Your Life recall Ernst Lubitsch’s Heaven Can Wait (a questionable life is reviewed to determine where the deceased should proceed next), Fritz Lang’s Liliom (an afterlife screening-room tribunal), and Alfred Hitchcock’s North by Northwest (a flashy, superficial adman gets stripped of his identity and rediscovers it with the help of an ethereal blond; the film’s closing shot). But no one can accuse Brooks of cloning this movie from some previous model, as Woody Allen nearly always does; this is a fresh and distinctive work that generates its own rules and bylaws, not a familiar trip down memory lane.

Indeed, much of the comic richness of Defending Your Life derives from the thoroughness with which it has mapped out the specifics of Judgment City. We see billboards and placards heralding the resort’s various events and attractions (“Welcome Kiwanis Dead,” says one); get glimpses of three coffee-table books in a reception lounge and all the TV channels available in the hotel rooms (including a soap-opera, a game-show, a talk-show, and a “perfect weather” channel); visit four restaurants, two hotel lobbies, a nightclub, and a miniature golf course; and are told about the recently built mini-malls on the outskirts of town. We learn about the quality of the hot dogs at the Past Lives Pavilion (where viewers can sit in individual booths and glimpse some of their previous incarnations, introduced by a Shirley MacLaine hologram) and even find out about some of the minor perks that favored guests receive. (Julia, Daniel discovers, is staying in a plusher hotel, has a Jacuzzi in her bathroom, and finds chocolate cream-filled swans on her pillow; he only gets breath mints.) The dreamlike, slightly overlit cinematography is by Allen Daviau, a longtime associate of Steven Spielberg, and the bleach-bland look of Judgment City may remind us slightly of Spielbergland. But what Brooks does with that resemblance ultimately turns Spielberg on his head: we become aware not only of the pastel-pretty, racially and ethnically homogenized white-bread fantasy — Los Angeles’s Century City sprinkled with gold dust by Tinker Bell — but of the fears that call this vision into being.

It’s a city modeled, of course, on the world the guests already know — down to their individual defenders, prosecutors, and judges. Daniel’s defender, played with juice and gusto by Rip Torn, is an affable salesman type who unctuously slides over information that he assumes Daniel won’t understand, while his prosecutor (Lee Grant) is a no-nonsense professional and “Dragon Lady.” When Daniel’s defender doesn’t make it to one of the examining sessions (“I was trapped near the inner circle of thought,” he later offers by way of explanation), he is replaced by the glib and reticent Mr. Stanley — a nice comic turn by Buck Henry, who manages to satirize most of the irritating lawyer traits left untouched by Torn and Grant.

During the examination periods, which occupy a fair amount of the movie, we see scenes from Daniel’s entire life, and most scenes are given contrasting interpretations by the defender and prosecutor (each of whom selects half the scenes to be reviewed), followed by comments from Daniel himself. (When the defender shows a scene with Daniel in his crib cutting short an argument between his parents with a brief, tearful cry, it’s to counter the prosecutor’s clip of Daniel at 11 letting himself get creamed by a playground bully. The defender’s gloss on the earlier incident is, “At this moment, he learned restraint.” Daniel’s comment is, “I feel very good about the restraint idea.”)

Most of these scenes are hilarious — there’s an especially riotous montage offering excerpts from “164 misjudgments over a 12-year period” selected by the prosecutor, a wonderful short compendium of sight gags — but it’s part of Brooks’s special slant on things to make some of the pro and con arguments about the clips even funnier. Taken as a whole, these tribunal sessions ultimately add up to an internal debate on Daniel’s part that runs parallel to — and alternates with — his nightly meetings with Julia and their developing relationship. The examinations and the love story increasingly illuminate one another and finally merge to become the same story.

According to the movie’s metaphysics, fear and stupidity are virtually the same thing. And nearly all of us in the world today are plagued by the resulting inhibitions — a problem illustrated with particular poignance when the possibility of sex between Daniel and Julia arises. Without a trace of pretension or posturing, Brooks expands this comic perception into a kind of testament about what we go to movies to find and what we do with our lives. It’s one sign of his achievement that his fourth brilliant movie is actually the first that ends without a three-part printed epilogue that explains what happened to the characters afterward. Thanks to the fulfillment that we and the characters share by then, nobody even has to ask.