From Film Comment (March-April 2012). — J.R.

Ever since Gilbert Adair died three weeks short of his 67th birthday, in London, I’ve been rereading him compulsively. And I’ve had a lot to choose from — not only many online articles (including pieces written for this magazine and for Sight & Sound), but all but one of the 18 books listed on the flyleaf of his nineteenth and last, And Then There Was No One: The Last of Evadne Mount (Faber and Faber, 2009) — the final volume in his inspired trilogy of Agatha Christie pastiches, which somehow manage to combine his taste for pop entertainment with his more avant-garde impulses, to riotous effect. Even though I eventually lost touch with Gilbert as a friend — whom I’d met in the early 1970s as a fellow habitué of the Paris Cinémathèque, and who years later was kind enough to broker my friendship with Raúl Ruiz (with whom he worked on several projects, including three that were filmed, and who tragically and prematurely died just a few months earlier) — I remained a steadfast fan who collected all his books.

For Film Comment, Gilbert made his first appearance in an interview with Jacques Rivette, conducted jointly with myself and Lauren Sedofsky for the September-October 1974 issue, available online at http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/1974/09/phantom-interviewers-over-rivette-with-gilbert-adair-and-lauren-sedofsky/ . After that, from 1977 through 1982, he contributed six London Journals, nine Paris Journals, a final journal “from a country manor,” a “cliché expert’s guide to the cinema,” and an especially memorable Mae West obituary — which includes a definitive tribute to Sextette, her 1978 swan song, which he called “the most extraordinary compliment ever paid by the medium to one of its stars” and “the most chivalrous film ever made,” adding that its “extreme fascination…derives not merely from its star’s age — she was 86 when she made it — but from the fact that the film pretends not to notice it.” (“To paraphrase Cocteau’s oft-quoted aphorism about Victor Hugo, Mae West is a madwoman who thinks she is Mae West.”)

A singular and highly gifted literary dandy, Gilbert was also a seasoned and voracious film buff — uncharacteristic for a writer in the U.K. (born in Scotland, but in fact a fully self-created English dandy and francophile), yet part of his essential baggage as a frequent Channel-crosser. Characteristically, in Paris he used to discard all the books he read except for those by Cocteau, whose volumes filled the shelves in his hotel room on Quai Voltaire, and one of his sadly unfulfilled dreams was to write a biography of his role model. (Check out his superb audio commentary to Les Enfants Terribles on Criterion.) Equally ambitious and self-critical, he often rewrote his own books when they went into second editions.

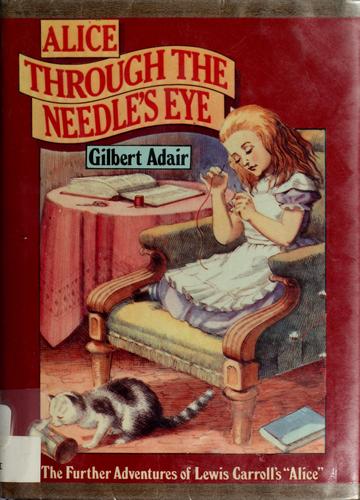

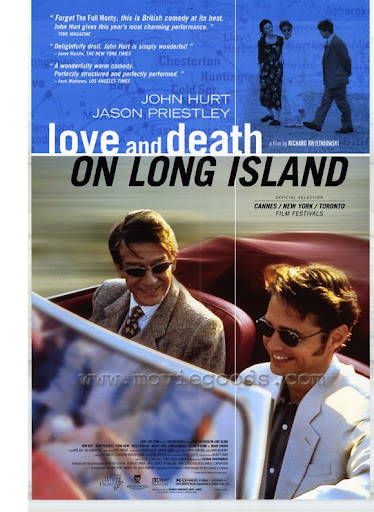

Almost half his books qualify as impressive pastiches: sequels to Lewis Carroll’s Alice books and Peter Pan, spins on Death in Venice and Les Enfants Terribles that later formed the basis for the film versions of Love and Death on Long Island and The Dreamers, a thriller conceived as a tribute to Hitchcock (The Key of the Tower), a joint takeoff on Barthes’ Mythologies and Perec’s Je me souviens “translated” into an English context (Myths and Memories), and the only book listed on his flyleaf that I don’t own — a brilliant Alexander Pope pastiche called The Rape of the Cock which I read in manuscript circa 1974. (In fact, I once strongly suspected that this remains unpublished; the only other bibliographic reference I’ve come across, “Caen: Editions Dom, 1991,” suspiciously sounds like a half-buried Adairian pun, caen+dom equaling “condom”, although I’ve subsequently been informed that this book actually exists.)

Most of his other books are film-related: obviously Hollywood’s Vietnam and Flickers, but also many entries in his two wonderful collections of “cultural” columns, The Postmodernist Always Rings Twice and Surfing the Zeitgeist. His adapted his own novel A Closed Book for a late Ruiz feature (subsequently retitled Blind Revenge) that was poorly received but deserved more attention than it got (and could still be purchased, the last time I checked, at amazon.co.uk), and even The Death of the Author features a telling interlude related to Lubitsch’s To Be or Not to Be.

He will be missed — but thankfully, he can still (and can always) be read.