From Film Comment (September-October 2011). — J.R.

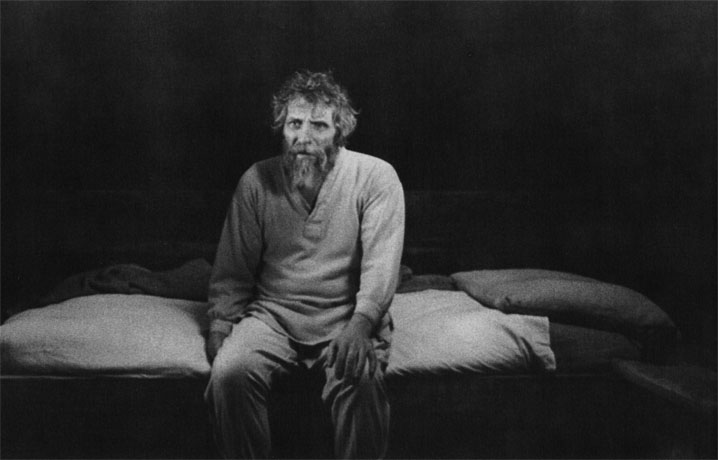

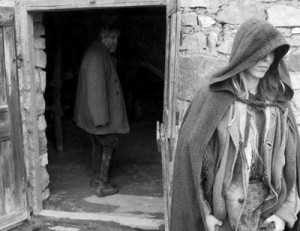

Recalling the incident in Turin that reportedly occasioned Friedrich Nietzsche’s final breakdown into madness — his weeping and embracing a cab horse that was being beaten by its driver for refusing to budge — Béla Tarr’s regular screenwriter, novelist László Krasznahorkai, has noted that no one seems to know or ask what happened to the horse. But The Turin Horse is only nominally concerned with this riddle. It’s more concerned with the horse’s driver and his grown daughter, who live in a remote stone hut without electricity, subsisting on an exclusive diet of potatoes and palinka (Hungarian fruit brandy) while a perpetual storm rages outside, then arbitrarily subsides, over a carefully delineated six days. Their abject life remains fixed by a few infernal routines, such as dressing, undressing, drawing water from a well, or looking out the window. (One exterior shot of the daughter doing just that towards the end of the film will haunt me the rest of my life). What passes for plot gradually becomes even more minimal by the driver’s horse first refusing to pull the wagon, then refusing to eat. Eventually father and daughter also become immobilized, confirming one of Tarr’s helpful statements — that this is simply a film about the inescapable fact of death. And Tarr is so unconcerned with the usual rules of consistency that he can show us the father and daughter (the latter played by Erika Bók, the little girl in Tarr’s Sátántangó and Henriette in The Man from London) theatrically lit while she refuses to eat, even though the previous scene, ending in total darkness, has shown the lantern repeatedly burning out while it’s still full of fuel. So “What is this darkness, Papa?” is a question that goes unanswered. This film is so bound up in what it’s doing that it can’t be bothered to care about explanations.

The other “major” incidents are no less perfunctory. A neighbor who’s run out of palinka stops by for a refill and expounds on the awful state of the world and those who “acquire,” “debase,” and “destroy” it. Perhaps because this is the film’s only extended monologue, some viewers are lured into thinking he must be expounding the filmmakers’ “message” rather than merely spouting bullshit (which is what the father suggests). But what Tarr and Krasznahorkai are offering is a vision, not a message. The only other visitors, two women and five men, arrive in a wagon drawn by two robust horses to fetch water from the well, all of them insanely cheerful; the father, who calls them fucking Gypsies and clearly despises them, orders his daughter to chase them away, and after one of them says to her, “Come with us to America,” he charges out of the hut with a hatchet, provoking their curses as they ride off. One leaves her a religious book about defilement that she reads aloud from, haltingly, in the next scene. The next day, she discovers the well has run dry, but this is no sort of “message” from the film either, neither retribution nor any sort of causal effect that we can be certain about. Like the neighbor sounding off or the lantern refusing to stay lit or the daughter refusing to eat, it’s just another facet of a universe that’s blighted by definition — and one that can’t be sentimentalized as a blight populated by salt-of-the-earth types, either. Ever since his 1982, 72-minute video production of Macbeth in two shots for Hungarian TV (available as an extra in the Facets edition of Sátántangó), Tarr’s universe has operated according to some sort of demonic anti-theology that’s more a matter of feeling than one of principle; it can’t even be counted on to confirm the triumph of evil or pestilence or futility. If this proves to be Tarr’s last film, as he now maintains, this may be because it goes beyond any necessity to reach final conclusions about anything but extinction.

I suspect the father partially hates the Gypsies because they’re so cheerful. I’m reminded of a hilarious early scene in Sátántangó — which has no Gypsies but shows most of its major characters peevishly and with great difficulty dismantling the furniture in their collective farm before they abandon it so that the cursed Gypsies won’t get their hands on any of it. (In conversation, Tarr confirmed to me that The Turin Horse, unlike Sátántangó, isn’t really Hungarian except for the palinka and “Gypsies” — and by the latter I assume he meant the everyday passionate Hungarian hatred for Gypsies more than the Gypsies themselves. Clearly the father doesn’t feel the same way about his gloomy neighbor or even his recalcitrant horse — whom he and his daughter drag along with great effort, in spite of the horse’s illness and uselessness, when, after the well goes dry, they attempt to escape. And why do they fail to escape?

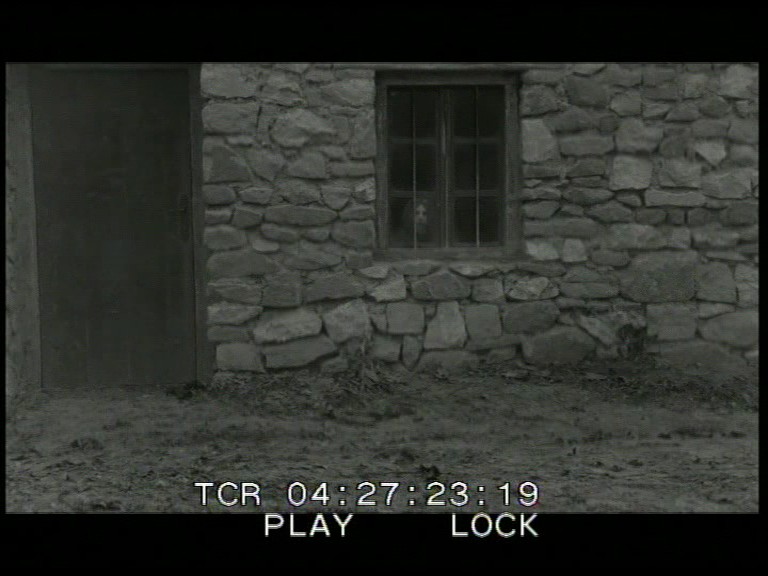

The film doesn’t say; that’s how little it cares about storytelling, apart from conveying the characters and their daily existence. Or unless we redefine storytelling as what the camera does whenever it moves, which happens to be most of the time. That comes close to defining the narrative of Sátántangó, thereby implicating us at every turn. But does The Turin Horse implicate us morally in the same fashion? Not really, because the turf has become more metaphysical than socio-political. Part of this film’s mystery is how much it can borrow from the expressive materials of Sátántangó (black and white, a droning minimalist Mihály Vig score, horrible weather, rural setting, slow and perpetual camera movements, seeming inactivity, a novelistic narrator summing up what the characters think, feel, and are at the end of various sequences) without expressing the same things or serving the same functions — as if Tarr and Krasznahorkai were contriving to turn a chair into a table, or vice versa. Sátántangó used a rain machine and this film uses a wind machine; Tarr is so adept at film illusion that many viewers still believe that he actually killed a cat in Sátántangó and that the hut here is some found object, not a constructed set. Like Kiarostami, he resents Hollywood so much that he winds up beating it at its own game, giving us the impression that he’s telling a story without actually doing so. The Turin Horse may offer an anti-universe according to some anti-theology, but it’s one that lives and breathes.

For me the abiding mystery isn’t what the film means but how and why we watch it. “Try not to be too sophisticated” was Tarr’s suggestion the first time he introduced it at the New Horizons International Film Festival in Wrocław, Poland. A sound piece of advice, but not easy for all cinephiles to follow, especially if the “sophistication” resembles Dan Kois’ pseudo-populism masquerading as common sense (“Eating Your Cultural Vegetables”) in the New York Times. Going beyond the usual middlebrow philistinism, this position suggests that audiences supporting art movies by Akerman, Costa, Kiarostami, Reichardt, Tarkovsky, or Tarr (strange bedfellows, these — back in the 60s they would have been Antonioni, Bergman, Bresson, Dreyer, Godard, or Resnais)– must be masochists wanting to impose their self-inflicted punishments on others.

Factored out of such reckonings are those who regard Star Wars, Amélie, Slumdog Millionaire, Avatar, Inglourious Basterds or even The Tree of Life as obligatory cultural vegetables. And meanwhile denying that sensible individuals can find pleasure in Tarr films ultimately means attempting to outlaw the possibility that any might do so. Clearly part of America’s eccentric mistrust of art and poetry is bound up with a bizarre association of both with class; the usual pseudo-populist position is to find such activity excusable only when it’s interlarded with religion and/or “entertainment” (which in most cases entails colonial conquest, revenge, violence and/or some form of mush). To fail in this sacred duty apparently means to make films that are lethally boring, so that Rivette’s 13-hour Out 1, even as a serial, allegedly can’t be fun and games like Twin Peaks.

Why, then, did I wind up at all three screenings of The Turin Horse in Wrocław, three afternoons in a row? Largely because of my fascination with how a film in which practically nothing happens can remain so gripping and powerful, so pleasurable and beautiful. I’m usually reluctant to compare an anti-cinephile like Tarr to any other filmmaker, but even though his diverse technical materials are completely different from those of Erich von Stroheim, there’s something about the sheer intensity of both filmmakers as they navigate from one moment to the next that makes the usual rules and logic of film narrative and even the usual practice of following a plot seem almost beside the point — a kind of distraction. The world of The Turin Horse isn’t unveiled or imparted or recounted or examined or told; it’s simply there, at every instant, as much as possible and more than we can think to cope with, daring us simply to take note of it.