From Monthly Film Bulletin, February 1976 (Vol. 43, No. 505). It’s worth noting that (1) this stinker made a fortune, which suggests that many people must have liked it, and (2) cinemas were required to book it for extended runs regardless of whether or not people showed up or liked it, making it the only movie showing for a lengthy time in many small towns that summer and thus making its profitability a bit of a self-fulfilling prophecy. — J.R.

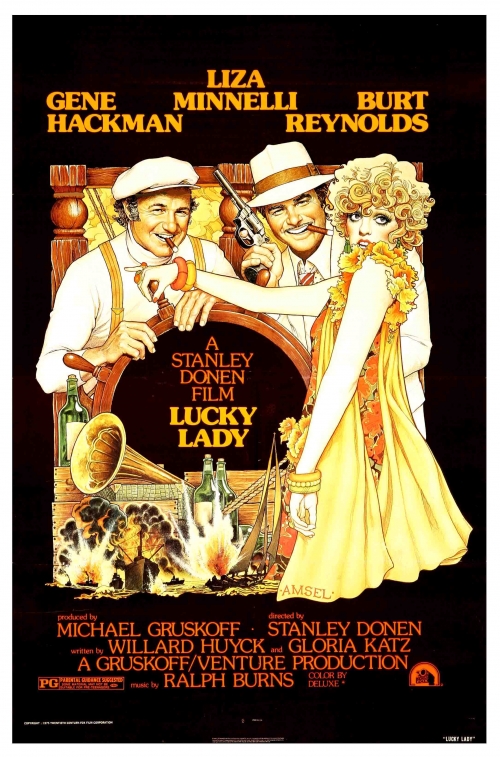

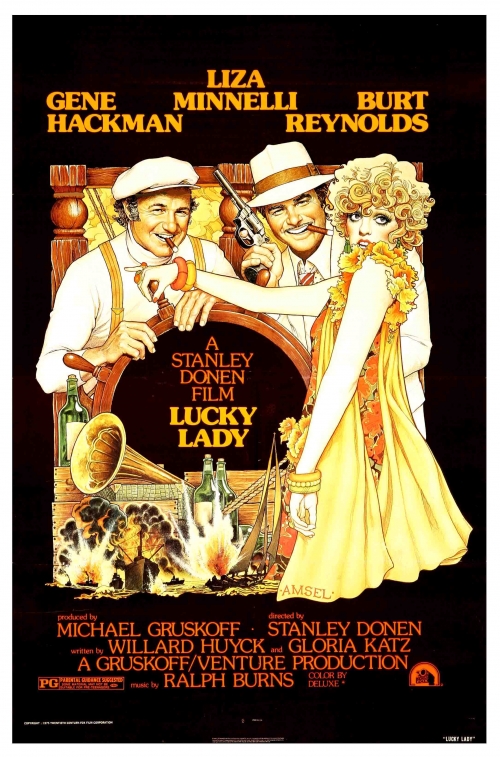

With an outsized budget estimated variously at $12,600,000 (Variety) and £10,000,000 (Daily Mirror), three box-office favourites and a script deliberately written, according to co-author Gloria Katz, as “the most commercial thing we could think up”, Lucky Lady is both conspicuously overproduced and undernourished.

The presence of Stanley Donen seems to count for little in a project that might more logically have been entrusted to a computer. All it has to express, quite simply, are its deliberations: to combine as many saleable features as can be packed on a screen within the space of two hours. A little of everything is thus tossed into the mixture; and a great deal of nothing emerges out of the isolation and autonomy of the assorted elements. Read more

From Film Comment (July-August 1999). I’ve done a light edit, trimming part of my original conclusion. It’s worth adding that at least two additional pieces about this film have recently turned up on the Internet — a new essay by Ignatiy Vishnevetsky (the first part of an ongoing series) and a detailed account by the late Gilbert Adair that was originally published in 1987, not long after Affaires Publiques was rediscovered in Paris.

I apologize for the poor quality of most of the illustrations from Bresson’s short film, which are the best that I could find. — J.R.

Ten years ago, I flew all the way from Chicago to the San Francisco Film Festival for a weekend to see Robert Bresson’s first film, which had been discovered in incomplete form at the Cinémathèque Française, bearing the title Béby Inauguré. Shorn of three of its musical numbers and now totaling 23 minutes, this rather elaborate piece of slapstick and surrealist tomfoolery was written and directed by Bresson and released in 1934, a full nine years before shooting started on his first feature, Les Anges du péché, and I had been hearing about it for years as an irretrievably lost curiosity. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 28, 2004). — J.R.

Like Mystery Train and Night on Earth, this feature by Jim Jarmusch is a collection of short stories, but it’s funnier and more formally adventurous than either; it’s also ultimately greater than the sum of its parts. Shot in black and white over 17 years, its 11 episodes feature actors and/or musicians, usually playing themselves and hanging out together in cafes while consuming caffeine and nicotine. One recurring theme is the ethics and protocol of being a celebrity (explored most impressively by Alfred Molina and Steve Coogan, and by Cate Blanchett in a virtuoso double role as herself and her own cousin); another is the everyday tension that can develop between friends and relatives. Among the two dozen stars are Isaach de Bankole, Roberto Benigni, Steve Buscemi, GZA, RZA, Bill Murray, Iggy Pop, Bill Rice, Taylor Mead, Tom Waits, and the White Stripes. R, 96 min. Music Box.

Read more

Read more