From the July 21, 2006 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

The Case of the Grinning Cat

*** (A must see)

Directed and written by Chris Marker

Narrated by Gerard Rinaldi

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Frank Tashlin

With Tony Randall, Jayne Mansfield, Betsy Drake, Joan Blondell, John Williams, Henry Jones, and Mickey Hargitay

Two cheery, even hilarious works that are informed by a surrealist spirit are showing this week at the Gene Siskel Film Center. Each says plenty about what’s wrong with the world, yet neither has a villain.

The Case of the Grinning Cat is a wise, somewhat whimsical hour-long video — a political commentary on Western culture by independent French writer-director Chris Marker, who turns 85 next week. From 2001 to 2004 he taped ephemeral phenomena on the streets of Paris — graffiti, posters, political demonstrations, glimpses of cats and musicians in metro stations — as he explored issues ranging from 9/11 and the invasion of Iraq to more local concerns. It’s all framed by a reverie about cartoon Cheshire cats that mysteriously appear in unexpected places, rather like the proliferating post horns in Thomas Pynchon’s The Crying of Lot 49.

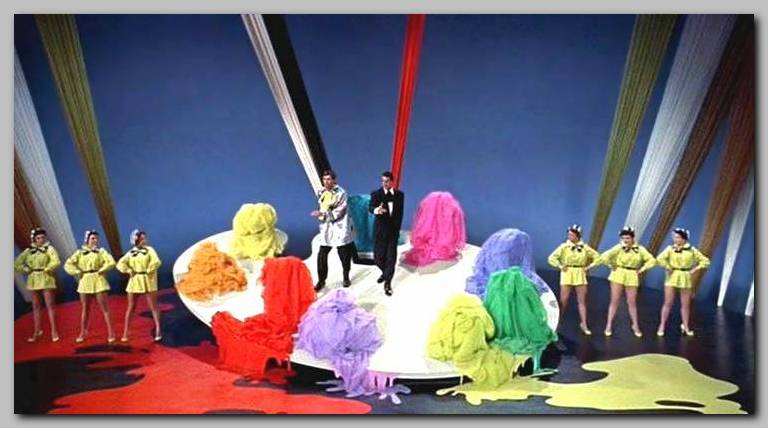

Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, showing in a sparkling new archival CinemaScope print, is a wild avant-garde satire of Western culture circa 1957 by writer-director Frank Tashlin. Very freely adapting a George Axelrod play, he focuses on ephemera in New York — advertising, television, celebrity culture, 50s breast worship. He also uses his background in Hollywood animation, molding his stars — Tony Randall and Jayne Mansfield, both giving their best performances — into cartoons. Randall’s a nerdy Madison Avenue executive with rolling eyeballs, Mansfield’s a tall, squeaking, Betty Boop-ish movie star with cleavage.

Tashlin once defined his turf as “the nonsense of what we call civilization,” which he thought deserved both exuberant celebration and ridicule. Marker’s amusement at human folly is much subtler and softer, and it’s laced with poetry, but it’s similarly detached. He’s always been a maverick, but he’s a contemporary of the French New Wave directors and even collaborated with a few of them, including Alain Resnais and Agnès Varda. No one’s better at filming people on the street or endowing them with a relaxed kind of nobility, but his flair for still photography and his keen sense of place are things he shares with his old cohorts. (At one point he uses the haunting score of Resnais’ Hiroshima, Mon Amour to accompany shots of a crowd mourning AIDS victims.) He also wittily combines diverse images and ideas in a way that suggests Jean-Luc Godard, though these days Godard seems more interested in the inside of his head than in everyday life.

Tashlin had a huge stylistic impact on the New Wave. Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?, his greatest film, is the template for Godard’s bold use of primary colors and ‘Scope in the 60s. (When I first saw it in my early teens I was so exhilarated by its irreverence and invention I sat through it twice.) Artists and Models (1955), Tashlin’s second greatest movie, about the 50s craze for comic books — starring four more Tashlin cartoons, Dean Martin, Jerry Lewis, Dorothy Malone, and Shirley MacLaine (and showing next week in the Film Center’s Tashlin series) — was the acknowledged inspiration for Jacques Rivette’s 1974 Celine and Julie Go Boating.

Tashlin is more admired in France than in most other places, and his genius remains a secret in the U.S. This can be ascribed partly to his unevenness. (Two of his lesser efforts are also showing this week, It’$ Only Money and The Man From the Diner’s Club.) But it can also be traced to his mentoring of Lewis, whom he directed in eight features, causing much confusion over who was the auteur. The recent American aversion to Lewis and the cherished myth that he’s strictly a French taste can be seen as a strange form of denial. Lewis was much more popular in the U.S. during the 50s than he’s ever been anywhere else, inspiring the kind of adoration accorded to Elvis Presley during the same decade. And his subsequent popularity in France was surpassed in many other countries. He’s more typically, hysterically American than some Americans like to admit, and so he’s become irritating rather than adorable — an infantile monster we seem to assume only the French could love. Similarily, Tashlin has been called vulgar by some American critics who prefer to downplay the vulgarity of his targets.

One way the original French version of The Case of the Grinning Cat — Chats Perchés (“Perched Cats”) — differs from other Marker essays is that it uses pithy intertitles alone to carry his ironic voice. When I described it last year in a column for the Canadian magazine Cinema Scope, I wrote that it was “shot on both sides of the Atlantic,” a mistake that probably stemmed from the snatches of Bush on CNN it includes as well as my faulty French. Paradoxically, the English version sounds more French: in the added voice-over the narrator recites, encapsulates, and comments on the intertitles, mispronouncing words like owl and Eisenstein. Given that Marker is bilingual and given the graceful English versions of his other films, this awkwardness is curious. I have to wonder if it’s the consequence of a belief that we Americans need our hands held.

A few of the jokey period references in Rock Hunter may require glosses. I count ten allusions to other mid-50s Fox releases or stars then under contract to Fox, the most significant being Marilyn Monroe. She’s never mentioned, but Mansfield is used as a broad parody of her, and there’s a veiled allusion to The Brothers Karamazov (a treasured Monroe project) and a bit about getting hitched in Connecticut (where Monroe married Arthur Miller).

Were these references product placement? Tashlin’s admission of complicity with the culture he was lampooning? Probably some of both. The movie seems revolted by American notions of success, but when some of the major characters finally renounce these ideas to follow their unglamorous dreams the movie seems to mock them. We can’t quite believe that Randall’s ad executive becomes a chicken farmer, and neither can Tashlin or Randall. Maybe that’s why the characters turn up in front of a stage curtain at the end, becoming abstract Brechtian commentators on their own dilemmas.

Still, when Tashlin acknowledges being implicated in what he’s satirizing, he’s good-natured and relaxed about it — making his populism and optimism as genuine as Marker’s. Both directors have a charming way of being devastatingly critical, affectionate, and hopeful at the same time.