From the Chicago Reader (September 15, 1989). — J.R.

TALES FROM THE GIMLI HOSPITAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Guy Maddin

With Kyle McCulloch, Michael Gottli, Angela Heck, Margaret-Anne MacLeod, Heather Neale, and Caroline Bonner.

Given the murky black-and-white photography, the fascination with repulsive medical details, the loony deadpan humor, the impoverished characters and settings, and the dreamlike drift of bizarre and affectless incidents, it’s difficult not to compare Tales From the Gimli Hospital with David Lynch’s Eraserhead. It’s also being distributed mainly (although not yet in Chicago) as a midnight attraction by Ben Barenholtz, the same man who launched Eraserhead on the midnight circuits a dozen years ago. Turning up here at the Film Center in Barbara Scharres’s “Films From the Lunatic Fringe” series, Tales From the Gimli Hospital isn’t an easy film to categorize, but invoking the name and weirdness of David Lynch gives you at least a rough idea of what to expect.

In many respects, Guy Maddin’s oddball independent Canadian production is distinctly different from Eraserhead. The sensibility at work here is neither painterly nor musical — the frames aren’t rigorously composed, and the eclectic editing rhythms are relatively stodgy and clunky — but steeped, rather, in the traditions of oral narrative and cinema of the late 20s and early 30s. The flavor of regional antiquity gives the movie much of its eerie charm and feeling of remoteness — a sense that everything is taking place long ago and far away, in a dark corner of an eccentric filmmaker’s mind.

I’ve been told that the independent film scene in Winnipeg consists of a lot more than Tales From the Gimli Hospital, but without having seen any samples, I can’t say how Maddin fits into this milieu. But he does claim that his feature was produced by Manitoba’s Extra Large Productions, a “Lockport-based film manufacturing company” established in 1910, which can certainly be linked to the movie’s ancient and otherworldly feel.

According to the somewhat facetious press kit:

“In the early 1920’s, Extra Large and Lockport were legitimate forces in the western world’s motion picture industry, with such major releases as The Enchanted Waterfall, Oh Hazell, Otto’s Little Auto, and Youthful Cuckold. The result of a merger in 1919 of Lockport’s Extra Color Repertory Theatre Company (with its strong work base in the operetta, parade and memorial service) and the Large Productions Photoplay Manufacturing company, Extra Large Productions had a virtual stranglehold on the Canadian film market, and was threatening Hollywood’s monopoly in the American Midwest marketplaces, when a series of disastrous investment decisions crippled the company in 1927. However, it wasn’t for lack of foresight that the company floundered, for it was its heavy backing of experiments in a primitive mechanical television, as early as 1925, which made conversion to sound — when it came to the industry in 1927 — financially impossible. Extra Large’s false step cost them the race, and for the next fifty-five years the company sold awnings and garden supplies to a Lockport populace that eventually forgot its glory years as a Mecca for international film stars.”

This history may be a total put-on — highly likely given the whimsical nature of the film itself, which wallows in ersatz Nordic folklore and local history — but if not, the company was started up again four years ago, and Maddin’s short The Dead Father and his subsequent feature are its first productions since the 20s. (The press kit also boasts that Tales From the Gimli Hospital is the first Extra Large production to cost over $5,000, which makes one wonder what could have induced the international film stars to turn up in the 20s.)

The movie begins in the style of a silent film, in sepia tones and complete with old-fashioned pictorial introductions to each of the major characters and music that sounds as if it’s performed at the bottom of a swamp. We arrive, via an extended camera movement, at the Gimli hospital, where a little boy and little girl are ushered into a room to see their ailing mother. As she listens to the radio, to deranged, repetitious music that sounds like a stuck record, the nurse, Amma (Margaret-Anne MacLeod), begins to entertain the children by telling them a tale, the story of Einar the Lonely and the lovely maiden Snjofridur (“It all happened in a Gimli we no longer know . . .”).

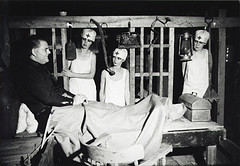

The film then switches to the story that Amma is telling, also done in a rather creaky silent-film style, but initially it seems incoherent, and it’s some time before we get to either Einar or Snjofridur. First we see a woman getting dressed, then a man rubbing himself with dirt and twigs, and finally several women running out of their houses to gambol in the woods together or lie on the beach while men wrestle nearby. Finally, we meet Einar (Kyle McCulloch); in front of his hut, he takes a fish and squeezes out its innards into his hair, which he then combs. He cuts his finger mending a net, and that night he sets off with two fish for the Gimli hospital (in an older and more decrepit state), falling into a nurse’s arms when he arrives. Feathers drift through the hospital ward like snowflakes, and we hear cows mooing and chickens clucking. (Much later, we discover that the hospital is located inside a barn, and that there are holes underneath every bed so that “animal heat” can drift up and warm the patients. There are also apparently holes in the ceiling so that the animal heat from the floor above can drift down — or at least that’s what I concluded when one of Einar’s fellow patients fires a gun and a bird falls to the floor.)

I’m not sure if the above is as incoherent a narrative as the film makes it appear; there are other details, including stuff about a mysterious epidemic, but it’s difficult to tell which ones are pertinent. After we witness the extravagant oral hemorrhaging of a dying patient (the film revels in digressive gore), Einar encounters Gunnar (Michael Gottli), the other leading character in this story, in the bed next to his — “a friendly, bespectacled, rather rotund gentleman,” as the press synopsis puts it, who is whittling a fish out of bark, which he shows to Einar.

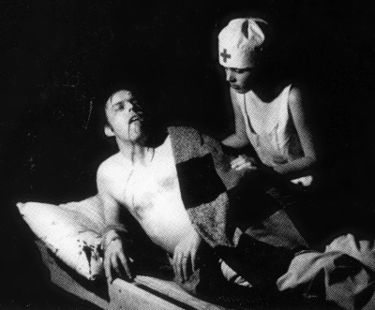

Eventually Gunnar tells an obscure story in an unnamed foreign language about three little sisters, which Amma translates offscreen while the film offers odd and oblique illustrations. Later that night (or is it several nights later?), a nurse climbs up on Einar’s bed to hang a sheet from the ceiling so she can make love to Gunnar, which Einar watches in silhouette. Frustrated, Einar climbs out of bed and eats one of the nurse’s white hats until Gunnar takes it away from him and puts him back to bed.

The next stage in the plot is a rather Woody Allen-ish comedy about deprived sexuality as Einar, feeling “invisible and mute” in relation to the nurses, who lavish all their attention on Gunnar, takes up “bark fish cutting and bark fish appreciation” as well as story telling, to little avail. Later, he and Gunnar each tell the other a story, and it emerges that they both concern the same maiden, Snjofridur (Angela Heck). In Gunnar’s story, he fell in love with Snjofridur, but, having been infected by the plague, passed his sickness on to her. On their wedding night he rejected her because of the sores the plague made on her body, and she died of a broken heart. In Einar’s story, he reveals that he came upon Snjofridur’s grave, stole all her burial tokens, and ravished her dead body. Eventually the two heroes wind up outdoors in a protracted and disgusting wrestling match as bagpipes play offscreen. Later, both cured of their illness, they emerge from the hospital to the strains of Mario Nascimbene’s score for the adventure epic The Vikings (1958).

As Amma finishes the story of Einar, the children’s mother dies. Amma explains to the children that their mother has gone to heaven, and when one of them asks what heaven is like, she launches into another story . . .

I’ve left out a campy, red-tinted musical number featuring a glamour queen known as the Fish Princess, as well as many other passing details. The plot, in any case, doesn’t really signify much except as an opportunity for Maddin to show off his creepy surrealism. Back in the 60s and 70s, this sort of trippy exercise was generally known as a “drug movie,” and if this one lacks both the rigor and the obsessive feeling of personal necessity that suffuses Eraserhead, it does have more moment-to-moment invention and genuine weirdness — as well as a higher solid-laugh quotient — than most other examples of the form. It’s not generally a kind of filmmaking that wears well over time (Eraserhead again being an exception), but one of its distinctive and more enduring pleasures, in contrast to the usual staccato force-feeding of Hollywood features, is its dreamy slowness, which Maddin manages to make pretty alluring.