From the San Diego Reader (June 15, 1978). Not one of my best reviews, and certainly not a favorite, but I’m reprinting it, after some hesitation, as part of the record, with only minor re-edits. I came to write this through my acquaintance with Duncan Shepherd, the film critic for the San Diego Reader from 1972 until late 2010 -– a protégé of Manny Farber who had followed him all the way from New York to southern California –- after I had been hired by Farber to return to the U.S. from London and take over his classes for two quarters in 1977 while he was on a Guggenheim fellowship, and then hadn’t been rehired there. Manny, as I recall, was mightily annoyed by this piece, and I can’t deny that some of our political arguments probably fueled the review, at least in part -– as well as some of the swagger in Farber’s prose, a regrettable influence on this occasion. (An afterthought: I was sharing a house with Raymond Durgnat around this time, and the “crazy mirror” metaphor in the final paragraph suggests to me now that he might have exerted some influence as well.) — J.R.

As a native of Alabama, I didn’t have to worry much about draft dodging in the late Sixties. All I had to do was stay in graduate school in Long Island , while a sizable portion of the good ole boys I knew from high school were busy enlisting. I didn’t understand it then, and I’m not any surer that I can understand it now. I went to Coming Home hoping to find a few clues.

As far as I was concerned, the boys back home were misguided fools, but they sure life a lot easier for me. Considering my privileged background, I might have managed to stay out of the war without their unwitting help. If I hadn’t been in graduate school, I might have faked a f-$ like some of the surfers in Big Wednesday, a movie that provides a very interesting contrast to Coming Home as far as social class, the war in Vietnam, and a San Diego setting are concerned. Fortunately, Fortunately, the good-natured jocks who were all too willing to offer themselves up as cannon fodder made such deliberations unnecessary.

And unfortunately, Coming Home can’t answer any of my guilty questions about these guys, because it seems to know as little about their war experience as I do. One of the two lead characters, Luke Martin (Jon Voight), is introduced to us only after he comes back –- a paraplegic and a former football player and hawk who’s lucky enough to encounter Sally Hyde (Jane Fonda), a volunteer nurse in his ward and a former classmate and cheerleader. The other, Sally’s husband Bob Hyde (Bruce Dern), gets introduced as an expert runner, insensitive spouse, and fire-breathing hawk who goes off to Vietnam, returns with a slight and accidentally self-inflicted leg wound and a gratuitous medal, and winds up drowning himself in the Pacific. Luke is portrayed throughout as a hero; Bob gets treated like a freakish lunatic that the movie never quite knows what to do with.

At least half of Coming Home touchingly harks back to a time in Hollywood filmmaking when movies were addressed to broad communities rather than isolated narcissists, when it was still possible to offer collective statements –- however rosy-fingered and misguided (e.g., The Best Years of Our Lives) –- that were motivated by a sense of civic responsibility. The only half essentially consists of naked maneuvers designed to keep the film from cutting too close, or saying too much -– or doing anything that might prevent the movie’s diverse currents from converging in a Hollywood wish-fulfillment glittering with glamorous star turns.

The dual aim is everywhere present, in all its schizophrenic clarity: (1) to bear witness to the devastation – physical, psychological, moral, and social – wreaked by the Vietnam war on American soldiers and their families; (2) to make as much money as possible. As contradictory and crazy as this double motive might sound, it is at the dead center of the everyday strain in current Hollywood thinking that argues that a movie like Coming Home can’t even make the public rounds unless it has ungainly gobs of “Oscar,” “most erotic love scene since…” and “the performance of his/her life” smeared over its features, closing off every possible pore – not only in the ads, but right up there on the screen.

The project, which apparently grew out of meetings of Jane Fonda with women married to paraplegics and quadriplegics, ultimately wound up as a committee affair with assorted members hashing out the creative decisions: Fonda, producer Jerome Hellman, associate producer Bruce Gilbert, director Hal Ashby, actors Voight and Dern, and a trio of writers (Nancy Dowd, Waldo Salt, and Robert J Jones). Inevitably, the results are a kind of palimpsest of overlapping cross-purposes that keeps the movie’s tactile surface needlessly clogged, its rhythm twitchy and restless.

A glaring example of surface distraction is provided by the medley of Sixties rock hits that drones incessantly on the soundtrack. Ostensibly designed to provide the spectator with instant nostalgic placements à la The Last Picture Show or American Graffiti, the idea backfires to such a degree that the songs become a barrier between Now and Then. Why does this happen? Partially, one suspects, because the late Sixties are still too close to many of our memories, which suggests that the real problem posed by the movie is not how to remember the war’s aftermath – which we’re all still living with – but how to forget it gracefully. Another part of the trouble may be the way that the songs are allowed to float over and seemingly bind together the movie’s fragmented structure, which comes across as a false kind of construction. Unlike the brilliant atonal score composed by Hans Werner Henze for Alain Resnais’ Muriel, which simultaneously allowed the fragmented incidents and details of that film to remain separate while joining the spaces between them into a common lament — in a story about memory that significantly gravitated around the excruciating effects of the Algerian war on a French soldier – the top-of-the-pops score in Coming Home pretends to erase the gaps between the film’s multiple concerns, setting up an implied emotional continuity that the remainder of the film has been unable to contrive.

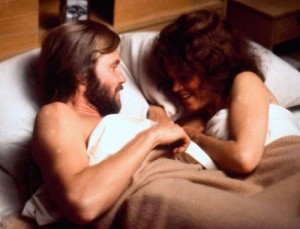

If Voight and Fonda represent the bankable side of the movie, they also can be taken as some measure of the film’s achievements. By focusing on so many mundane, everyday aspects of Luke’s paraplegic condition -– from urine bags to wheelchair to the mechanics of his lovemaking –- the film succeeds in humanizing his plight in concrete rather than sociological terms. When he pays his first visit to Sally’s bungalow flat, it is characteristic that the film devotes three utilitarian camera angles to show us how he gets off his wheelchair to make it through the front door — a process that is delineated logically rather than rhetorically. By introducing Vought as a grouch throwing a Brando-style tantrum from his hospital stretcher, the movie craftily paves the way for a step-by-step charting of his emotional rehabilitation that allows the character’s moral strength to grow before our eyes, lending an erotic charge to his lovemaking scene with Fonda -– the movie’s emotional centerpiece –- that has been carefully prepared for.

At the same time, I wonder what the movie might mean to all the male paraplegics who don’t get invited to dinner and bed by Jane Fonda: is it “telling their story” too, or merely rewriting it so that we all might feel a little more comfortable with their nagging presence? At least the movie acknowledges their problems in a series of tidbit cameos, which is a better deal than the Bruce Dern character gets. The coyly named Bob Hyde, who remains a psychological and sociological question mark throughout, winds up getting used more as a villain to offset Voight’s and Fonda’s glamor than as a coherently tortured victim in his own right. Adding insult to injury, the poor creep is saddled with enough insensitivities and manic tics to defeat a battleship, much less a human being. Not only is it clearly signaled to the viewer in the first reel that he can’t bring his wife to orgasm (a feat performed by Luke the first time he and Sally hit the sack); when she flies all the way to Hong Kong to visit him on leave, and soothingly caresses his back with Tiger Balm, all he can do is grill her brutally about her job in the paraplegic ward: “Is that the way you massage the basket cases at the hospital?” To take the movie at its word, the only reasonable thing such a raving cuckold can do –- he wanted to be a war hero, and comes back with an identity crisis –- is to photogenically drown himself in the ocean, thus clearing the way for the box-office dynamite of Fonda and Voight to flourish in the spectator’s imagination without any excessive overlay of guilt.

Despite and even at times because of such difficulties, Fonda’s way of immersing herself in all this material is a marvel to watch and is the main reason I can think of for going to see this movie. It isn’t that the character she plays has any solid depth on a conceptual or political level; her place in the film is essentially that of an emotional conduit between Voight, Dern, and the audience, which doesn’t allow her much additional space as an independent being. What fascinates and involves me in her performance are the conscientious effort and thought that seem to go into every line reading and gesture, as if the question of what a captain’s wife and former cheerleader was like became a source of endless curiosity and discovery for her. Some of the same concentration registers in a less showy fashion in Penelope Milford’s performance as Vy, Sally’s best friend and sidekick. By all counts the best scene in the film -– apart from the seemingly improvised conversations between war veterans that come before the credits, which promise an overall authenticity that the movie mainly doesn’t deliver –- are the ones featuring Fonda and Milford together, which bristle with small and telling observations.

The basic problem with such scenes, like most of the movie’s best opportunities, is that the film doesn’t seem to trust them enough, and usually cuts away from them to something else before they can suggest too much. In comparable fashion, the overall impact of two important sequences –- the suicide of Voight’s friend and Vy’s brother Billy, and Voight’s impassioned antiwar speech to a group of high school students -– gets compromised by the movie’s overkill strategies. In the first case, one has to contend not only with the ominous nudging of “Sympathy for the Devil” on the soundtrack, but an actual boost in the music’s volume level to punctuate the climactic moment -– as if the incident wasn’t already distressing or meaningful enough on its own terms. In the second case, Voight’s tearful outpouring is maddeningly intercut with the ceremonial preliminaries to Dern’s own suicide – which might have looked swell on paper, but comes across as an emotional equivalent of coitus interruptus on the screen.

If we can read Coming Home as a troubled crazy mirror of our own uncertainties, the schizophrenia of its methods begins to seem inevitable. To some extent, we all want o know how to cope with the atrocity in our minds that America’s involvement in Vietnam created -– a problem that’s clearly going to remain with us for some time. At the same time, most of us would probably prefer to assume that such a problem doesn’t exist –- a bias that most popular forms of filmgoing tend to oblige. Doing its best to look after our confused needs, Coming Home tries to remember and forget with equal amounts of dedicated intensity, as succeeds in keeping us just as muddled as we were, meanwhile providing an emotional outlet to our confusion. Just what we all need, isn’t it?