From Film Comment, November-December 1992. I’m not sure which of the stills directly below is printed backwards, so I’m including both of them.– J.R.

My 13th year at the Toronto Festival of Festivals reconfirmed my feeling that it’s large enough to satisfy many disparate and even contradictory viewing agendas. But even with a reported 320 films this year, it can’t be said to accommodate every taste. That is, one can generally count these days on the festival showing every new film by Paul Cox, Manoel de Oliveira, Henry Jaglom, Stanley Kwan, and Monika Treut, but not every new feature by Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin, Raul Ruiz, or Trinh T. Minh-ha (whose latest offerings were all absent this year) — or any work at all by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Harun Farocki, or Leslie Thornton. Certain thresholds are maintained regarding difficulty, and while Toronto audiences are possibly the most polite and appreciative that I know of anywhere, the programmers don’t seem eager to test their limits. After the screening of his delightful and significantly titled Careful, Winnipeg weirdo Guy Maddin pointedly observed that if a Canadian sees a great movie, he or she says it’s pretty good, and if a Canadian sees a terrible movie, he or she says it’s pretty good. Going with the flow, I found all the movies I saw in Toronto this year pretty good.

At least one of them, however, was flat-out great — the best Hong Kong film I’ve ever seen, and one that whets my appetite for something I previously had no contact with, the silent Chinese cinema. Known as Ruan Ling Yu in Mandarin, Center Stage (or Centre Stage) when it showed in Berlin, and now Actress, Stanley Kwan’s feature about Ruan Ling Yu (1910-1935) — the silent tragedienne of the Shanghai film studios, known as the Chinese Garbo — is an awesome object lesson in how to treat both history and film history so that they grow rather than recede in our psyches. Coscripted by Chiao Hsiung-Ping [better known in the West as Peggy Chiao], the polemical and prolific Taiwanese film critic (she published nine books last year, and is closely identified with the Taiwanese New Wave) and Qiu Gangjian (the eclectic director of Ming Ghost, who has translated Jean Genet into Mandarin), Actress intercuts documentary research with both archival evidence and fictional re-creations so that all three become part of a complex weave, while Kwan’s beautiful mise en scène integrates painted black-and-white backdrops (both on and off simulated Shanghai soundstages) with three-dimensional color sets behind worshipful framings of Maggie Cheung as Ruan to create similarly ambigous perspectives in the heart and mind. Cheung was the last-minute replacement for the less “lightweight” Mainland actress Anita Mui. but imagining Actress without Cheung’s classy poise and incandescent presence is tantamount to visualizing Gertrud in color (as Dreyer originally conceived it).

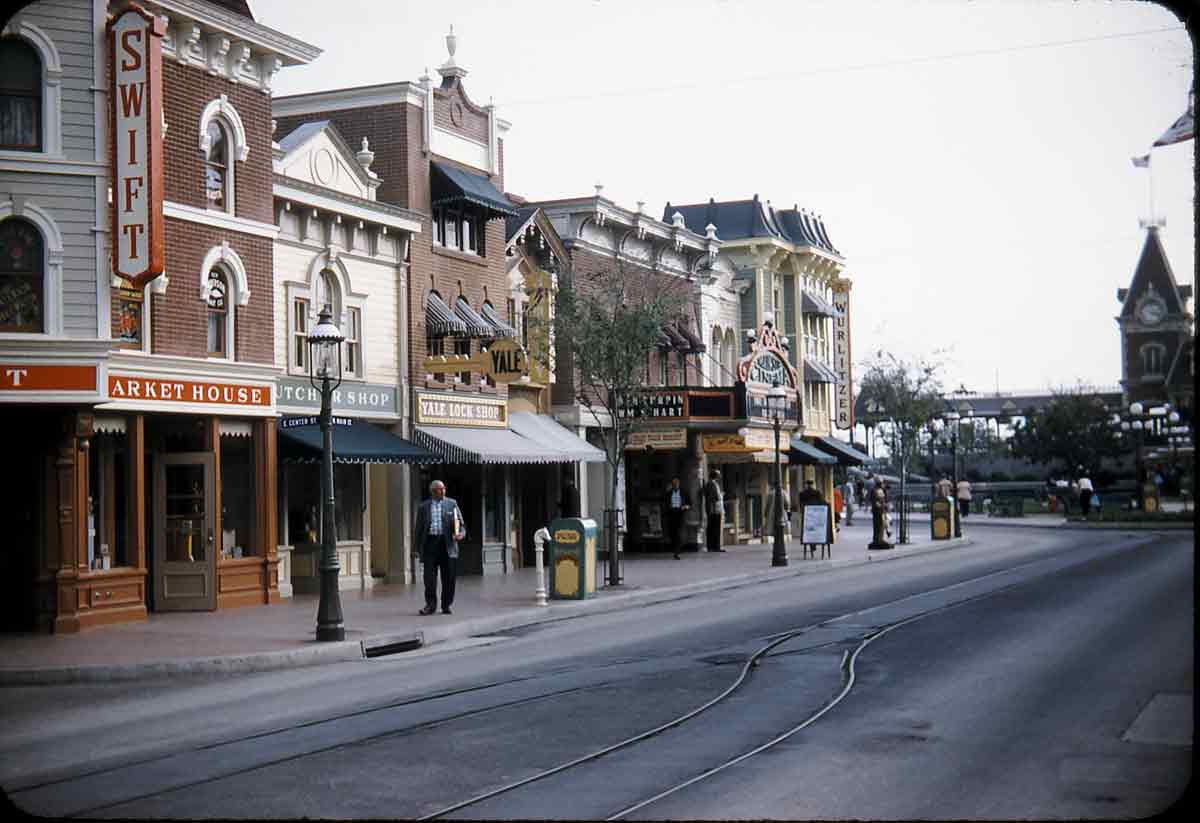

Our usual sense of how movies should treat the past seems to follow the model of Disneyland’s “Main Street, U..S.A.,” where every brick and shingle is five-eighths the original size so we don’t feel overwhelmed by the world of our ancestors. This movie, by contrast, is so open-ended and speculative about both the Thirties and why its heroine committed suicide (something that we’ll never truly have the final story on, although gossip-mongering in the press probably played an important role) that it becomes infinitely vaster than the present. It’s a film that refuses closure and never ceases to blossom in one’s imagination over its spellbinding 146 minutes. Indeed, the superiority of past to present is even a function of the films’ form, not merely an expression of its content. Interview with surviving witnesses and superficial chats about Ruan between Kwan and Cheung in black-and-white super-8 and video are easily surpassed in depth and resonance by re-creations of the past in color, but these gorgeous re-creations are exceeded in turn by clips from Ruan’s ravishing silent pictures. It could be argued that the relative flatness and superficiality of the present here, as in Kwan’s Rouge (1988), is not necessarily part of the filmmaker’s conscious design, but frankly I couldn’t care less: as with Gilda, it’s the results that count, and the luminosity of this film’s relationship with the past is the most exciting thing I’ve seen in movies all year. (By contrast, the most that a stateside masterpiece like Unforgiven can do is reconcile us to our own awfulness as compulsive self-deceivers — useful work, but not exactly energizing on the same level.)

Actress has not fared well in Hong Kong because, as with Wong Kar-wai‘s Days of Being Wild (1990), there is no place — yet — for art films in that populist movie culture. I don’t know about the fate of Li Shaohong’s Family Portrait in mainland China, but most of my Western and Asian friends who’ve seen it like it less than I do, perhaps because there is no place yet for comic soap opera in their arthouse view of “Fifth Generation” Chinese cinema. For me, quite apart from the director [see photo below]’s adroit and McCarey-like handling of her actors, this movie is already fascinating for its glimpses of contemporary life in Beijing — everything from the everyday censorship in the photojournalist hero’s session with a magazine editor to a scene of outdoor social dancing, to a police raid of a black-market labor pool.

The plot itself seems quintessentially Chinese: an urban photographer discovers that his first wife –a peasant he married when he was sent to the country during the Maoist period — has died, leaving behind a young son whom he unknowingly fathered. Bringing this boy to the city, the hero parks him at his darkroom and proceeds to dither, not knowing how to break the news to his second wife and son, especially after he learns his wife is pregnant again and has to go for an abortion. Comically matter-of-fact and intermittently critical of all its characters, Family Portrait coveys a directness and freshness that has not been apparent in the artier 5G work I’ve seen (including the same director’s previous feature, Bloody Dawn, a rather abstruse adaptation of García Márquez’s Chronicle of a Death Foretold. But, sad to say, curiosity about how ordinary people in the world’s largest country currently live — as opposed to the consumerist male fantasy of what it might be like to have three wives and a château in Raise the Red Lantern — is apparently not wide enough to get this film a U.S. distributor.

***

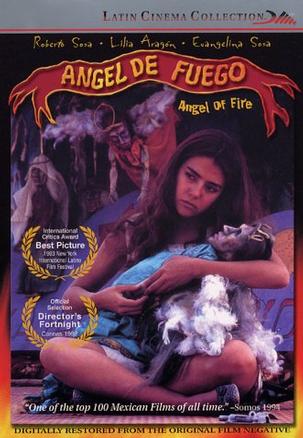

Beautifully assured in its economical, elliptical storytelling and its selective uses of both color and sound, Dana Rotberg’s corrosive, Bressonian, and Mexican second feature Angel of Fear follows the embittered progress of a 13-year-old circus performer from her impregnation by her dying father (a clown) to her adoption by a religious fanatic who runs a traveling puppet show with her two sons. Though the harshness of the impoverished milieu and the violence of the plot make this sound like a shocker (“Jodorowsky meets Tennessee Williams,” a New York colleague said approvingly), what’s more impressive about this tale of hatred and revenge is the steely calm and quiet control with which Rotberg tells it.

Much more popular was Sally Potter’s sumptuous, painless,and politically correct adaptation of Virgina Woolf’s Orlando, with an adept star turn by Tilda Swinton — pleasurable to the eye and (thanks to Potter’s composing and singing talents) the ear, though a mite simple and academic in its dogged efforts to provide the ultimate mainstreaming of Seventies Screen theory. As a longtime fan of Potter’s unheralded previous feature, The Gold Diggers (1983) — which I find wittier, stranger, and more beautiful (with Babette Mangolte’s best black-and-white cinematography to date) — I can readily understand her decision to aim for the upscale Greenaway market after nine years in purgatory, but my strongest hope for Orlando is that it will stimulate enough interest in the earlier movie to make a long-delayed video release feasible. [2010 postscript: Another 18 years would pass before this happened, when a DVD was finally released by the BFI earlier this year.]

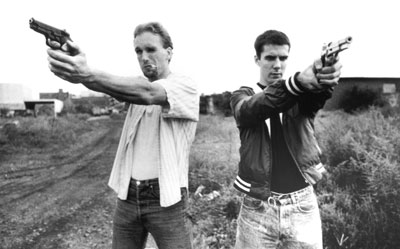

English-language independent features in Toronto seemed to fall into two general categories: screaming Italians à la Scorsese (Laws of Gravity [see above], Mac, Reservoir Dogs) and quaint cultural-ethnic interfacing à la Jarmusch (Autumn Moon [see above], In the Soup, Zebrahead). Quentin Tarantino’s grisly Reservoir Dogs, which won Toronto’s first International Critics’ Prize for best first feature, was probably the best of this lot, though the direction of actors in Nick Gomez’s Laws of Gravity was also quite impressive.

Less marketable but more trailblazing that either were two dirt-cheap, hour-long videos transferred to 16mm by New York filmmakers looking for a way out of current budget crunches. Michael Almereyda’s Another Girl, Another Planet, shot with a $40 PXL-vision camera in a few claustrophobic locations, may be a monetary step down from his Kansas comedy Twister (1989), but for me it’s a step up in poetic ambience, actorly funk, and French New Wave charm, with funnier dialogue to boot. The only drawback is that its intimacy is better served by video than by film, but without a film transfer it couldn’t have shown at the festival. Armond White has already written in these pages about Mark Rappaport’s deceptively comic and ultimately tragic Rock Hudson’s Home Movies (July-August), so let me simply add here that its brilliant uses of thematic and gestural indexing suggest a fascinating new direction for film criticism — not a form of criticism amenable to print, but certainly one that’s available to anyone with two VCRs and some time and thought to spare. Given the almost total passivity of the audience as it’s currently constituted, which the industry uses to validate its escalating abuses, Rappaport’s critique offers a profound utopian alternative: a means of talking back to the screen that potentially could (and should) spark a media revolution.

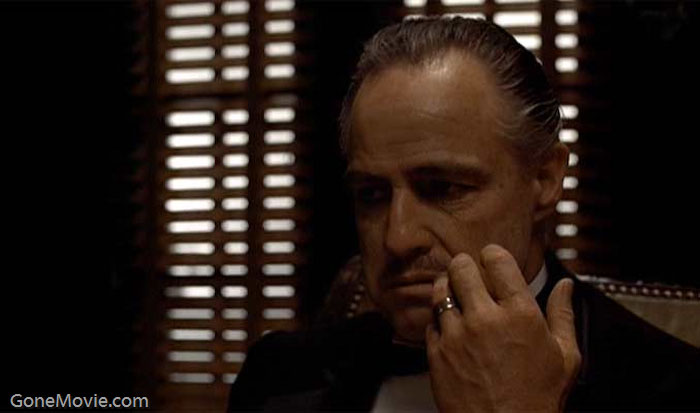

My only serious criticism of Visions of Light: The Art of Cinematography — a superb documentary by Arnold Glassman, Todd McCarthy, and Stuart Samuels, coproduced by the American Film Institute — is its subtitle. Notwithstanding a few token clips and talking heads that are awkwardly called upon to represent everything that this survey routinely factors out, the insertion of “American” and/or “Hollywood” before “Cinematography” would be more honest and accurate. Otherwise, this conventionally but impeccably made sound-bite and image-bite account of movie cinematographers benefits not only from the correct aspect-ratio clips but also from the erudition, intelligence, and ideas of the artists themselves. Whether it’s Ernest Dickerson recalling his childhood responses to Guy Green’s work on the 1948 Oliver Twist or the late Nestor Almendros comparing the respective light sources of lanterns in Murnau’s Sunrise and Malick’s Days of Heaven, the strongest thing about the commentaries here is that they deal with specifics: Gordon Willis explaining how his lighting on The Godfather was largely dictated by Brando’s makeup, Vittorio Storaro recounting the intricate symbolic color coding he had in mind for The Last Emperor.

Though hardly major, Manoel de Oliveira’s The Day of Despair is still a marked improvement over his Divine Comedy of last year, and at 76 minutes it provides a kind of piquant afterthought to the four-hour Doomed Love (1978) and the nearly three-hour Francisca (1981), perhaps his two greatest works. The first of these adapts a famous work by the 19th century Portuguese novelist Camilo Castelo Branco; the second adapts a novel about Castelo Braco; and The Day of Despair — based on Castelo Branco’s correspondence towards the end of his life, when his encroaching blindness drove him to suicide — completes the trilogy. Castelo Branco died at 65; Oliveira is about to turn 84. What continues to inspire awe about the prolific late flowering of this Portuguese Dreyer is how varied yet homogeneous his garden of works has become. No two Oliveira films are alike, yet in its obsession with the full measure of the romantic spirit this modernist epistolary film provides a haunting commentary on many of the others.

— Film Comment, November-December 1992; tweaked February 11, 2010