Commissioned by the French film magazine Positif and published, as two separate but adjacent pieces (critical article and interview), in their 158th issue (avril 1974). I don’t recall it ever appearing before now in English, at least in its entirety. I’ve given it a light edit. The interview was conducted by correspondence, with me in France and McBride in the U.S.

Happily, all three of the McBride films discussed here are available on DVD — David Holzman’s Diary and My Girlfriend’s Wedding paired together in the U.K. (with liner notes by me, available here) and Glen and Randa in the U.S. — J.R.

Due to their limited visibility, the three films of Jim McBride have tended to lead semi-legendary existences. Like seeds scattered to the wind, they’ve cropped up in unexpected places: DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY (1967) has been shown at film festivals (it won prizes in Mannheim and Pesaro) and cine-clubs, but not in theaters; MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING (1969), an hour-long film that is not easy to program, turned up on the Second Channel [in France] in a Sunday night “Cine-Club” (autumn 1972), but has rarely been seen elsewhere. GLEN AND RANDA (1971), seen much more widely in the United States — and even making Time magazine’s “Ten Best” list of that year — has been slow in reaching Europe, and surfaced in Pesaro only last September.

Jim McBride was born in New York City on September 16, 1941, and grew up there: his first two films are particularly New-York-infested works. He attended Kenyon College in Ohio, then the University of São Paulo in Brazil and the film school at New York University. In addition to directing, he has worked as a film reviewer, an editor, and a soundman.

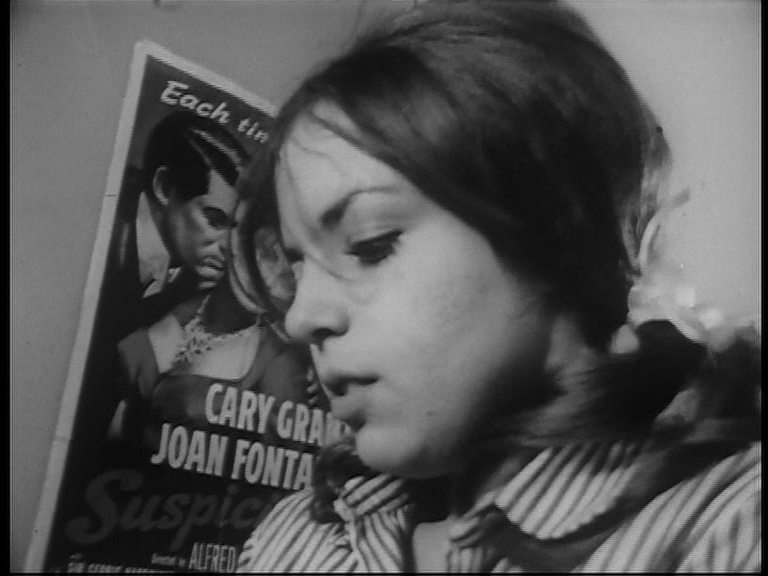

DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY created something of a stir when it appeared in New York in the late 60s. A fake documentary purporting to be the film diary of an imaginary character named David Holzman over nine days, it describes the dilemma of a young filmmaker who tries to grasp the essentials of his life by filming them. beginning with the observation that “My life…haunts me.” (1) His experiment results in disaster: his girlfriend (Eileen Dietz) leaves him when she can no longer tolerate the prying voyeurism of his camera, his painter friend (Lorenzo Mans) mocks him by saying that “your life is not a very good script,” and when we last see him, he is reduced to completing his diary with minimal sounds and images — snapshots and a record of his voice, both made in booths — after all his film equipment is stolen.

MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING, originally conceived as a short to accompany McBride’s first feature (see the following interview), confronts the dialectic between documentary and fiction from the opposite angle. A “true” inventory of McBride’s life at the time, it records the marriage of his English girlfriend Clarissa to a Yippie activist, which takes place solely in order to let her remain in America. (McBride himself was married to someone else.)

“As soon as you start filming something,” David Holzman’s friend warns him, “whatever happens in front of the camera is not reality any more….And you stop living somehow. And you get very self-conscious about anything you do. ‘Should I put my hand?’ …’Should I place myself on this side of the frame?’ And your decisions stop being moral decisions, and they become aesthetical decisions.” Lorenzo Mans, who utters these lines — and later collaborated on the script of GLEN AND RANDA, which was based on his own original story — is a friend of McBride, and once described his speech to me as McBride’s “misremembering” of something he once actually said: autobiography transformed into fiction. MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING, on the contrary, is true autobiography offered as spectacle. The film opens with Clarissa holding up a mirror to catch the reflection of McBride filming her (or not quite: the film, like DAVID HOLZMAN, is photographed by Michael Wadleigh, the director of WOODSTOCK, ad McBride sits next to him); it ends with a three-minute home movie of Jim and Clarissa on their “honeymoon” trip from New York to San Francisco, accompanied by an Al Cooper song, “I can’t Quit”. By presenting their own actions and motivations as significant, McBride and Clarissa virtually turn themselves into actors, and raise the question of whether their decisions or moral or aesthetic; in DAVID HOLZMAN, the actors turn themselves into “real people” by furnishing their parts with elements from their own lives.

GLEN AND RANDA, a science fiction film done somewhat in the manner of a documentary, strikes off into new territory, although it echoes some of the paradoxes of the previous films (e.g., Steven Curry and Shelly Plimpton, who play the leads, are actually husband and wife). The magnetic poles animating this curious fable are not so much the post-nuclear-war couple named in the title as the two old men who stand at opposite ends of their quixotic journey, their sages and spokesmen: a corrupt magician and a saintly fool.

Many years after the holocaust, when the film opens, the magician (Garry Goodrow) appears with his motorcycle, junk-filled trailer, and show-biz spiel, displaying the wreckage of civilization — appliances, comic books, gadgets, maps, peanut butter, pornography, toys, and other exotic leftovers –to a nomadic tribe of semi-literate suvivors, Glen and Randa among them. Spurred on by visions of a mythical city gleaned from a map of Idaho and a Wonder Woman comic (Metropolis), Glen drags Randa and himself across endless stretches of mountains and wilderness, even after Randa becomes pregnant, until they reach the sea. There they encounter another old man, Sidney Miller (Woodrow Chambliss) — an eccentric, sedentaryfisherman embodying the kind of sanctity that civilization scarcely touches — who installs them in a friend’s abandoned trailer, where Randa can have her baby. She dies in childbirth, and Glen sets off in a boat with his newborn son, Sidney Miller, and a goat, still believing that he will find his imaginary city.

Like McBride’s first two films, GLEN AND RANDA pays nostalgic tribute to the sort of junk and gratuitous rituals that fill up civilizations and living rooms; but unlike them, it examines these emblems at the point of extinction. It appears significant that, after the cross-country trip concluding MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING, GLEN AND RANDA should be filmed in California, and that the magician and fool should reflect, respectively, “East Coast” and “West Coast” sensibilities. As Rudolph Wurlitzer, another collaborator on the script of GLEN AND RANDA, has remarked in another context, “Forms have disintegrated here [on the East Coast] so you’re involved in disintegration. But out there [on the West Coast] forms just aren’t there. In that sense it’s a weird frontier, where you don’t have to be historically located.” (2)

Pointing to part of the coastline that used to be western Idaho, before it plunged into the Pacific, Sidney recalls the good old days to Glen and Randa: “Howie Hawks owned all that land in there. He grew the best potatoes in Idaho.” And in a very direct way, GLEN AND RANDA is the wreckage of a Hollywood tradition once exemplified by Hawks, a landscape without enough memory or resonance left to make myths possible, presided over by two old men and traversed by two lost children. (The latter’s clumsy trek across the wilderness with a horse in tow, the limpest part of the film, registers as a “failed” Western.)

Inevitably, the film’s witty and imaginative script distributes its better dialogue and its finest scenes to the two old men, who dramatize the respective wanderlust and domesticity of Glen and Randa far more effectively than the couple do themselves, with only a language of borrowed fragments to speak with. Some of this imbalance may also come from Steve Curry’s performance as Glen, burdened with the incongruity of an all-too-urban accent and an apparent confusion of innocence with stupidity, which Shelly Plimpton’s charm as Randa (in a simpler role) only partially alleviates. But the extraordinarily beautiful part of Sidney Miller, as written and played, more than makes up for the occasional irritations. Blessed with a shrill turkey’s voice, a Hemingway beard, a shy countenance, and the good-natured capacity to entertain any idea proposed to him, no matter how outrageous, he single-handedly turns much of the film’s latter section into a mystic celebration, particularly in a remarkable scene that shows him explaining his daily ceremony on the beach.

Since GLEN AND RANDA, McBride has been involved with two other film projects — GONE BEAVER and THE BROTHERS FRIGIDAIRE — neither of which has come to fruition. More recently, I have heard that McBride is about to start work as a taxi driver in New York City. “It all comes down to show business in the end,” the magician mutters philosophically at one point in his patter, and McBride’s difficulties in pursuing his career as a director seem to bear out this sad observation.

***

How did you get into filmmaking?

I got interested in movies when I was living in Brazil in 1960-61. At that time, you could see movies for about 15 cents. I had discovered that in French and Italian films you could see bare tit, so I went a lot. It never occurred to me at the time that an ordinary person could get into the movie business, but a year later when I returned to New York and started going to New York University, I discovered that there were lots of ordinary people studying to do just that, so I did it too.

How did the idea of DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY evolve?

It was in the mid-sixties, when cinéma-vérité was rearing its head, and people like the Maysles brothers were going around saying that now, for the first time, movies could tell the Truth, as if it were merely some technological problem. I was very interested in that, and in fact, Kit Carson and I had set about to write a monograph for the Museum of Modern Art on the subject. (We never finished it.) There was also an underground filmmaker named Andrew Noren who was making some very curious films at the time, films in which he would attack his subjects in front of the camera to try to get them to break down and reveal their “true” selves. I was also living a solitary West Side life at the time, much like David’s. How the idea for the film came about, I couldn’t say — a shot here, a line there — it came very slowly and in fragments.

DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY and MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING seem to be very complementary works; in a way, they mean more together than they do separately. Was this intentional?

MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING was originally conceived to be a short to go with DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY. Paradigm Films, who were going to distribute DAVID HOLZMAN, asked me if I could think of an idae for an inexpensive short, and this immediately occurred to me. We shot it in one day. It turned out to be longer than the 30 minutes or so that we had planned on, and when it was finished, they decided to distribute it separately. Soon after that, they folded their distribution operation, and to this day, it has not been seen publicly more than four or five times.

Some members of the audience are confused by DAVID HOLZMAN and think that they’re watching a real diary before the final credits come on. Have you encountered spectators who think that MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING is a fiction film?

At the time I made it, I was fond of referring to it as a fiction film, because it was very much my personal idea of what Clarissa was like, and not at all an objective or truthful view.

To what extent was MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING predetermined by advance planning?

To a very slight extent. I had the idea about the mirror, and the idea of the purse, and I planned for us to film the wedding. I didn’t know what was in the purse, and didn’t rehearse anything, but of course, our having recently gotten to know each other was a sort of rehearsal for the film.

How did GLEN AND RANDA originate?

My friend Lorenzo Mans had written a couple of semi-fantastic stories that I had liked a lot, and it had been my intention for some time to collaborate with him on a script. So, when DAVID HOLZMAN began to be talked about here and there, it seemed possible that money might be raised for a script of ours and we set to work. I had read several post-holocaust science fiction novels, and although they were very trashy novels, I liked the lanscape a lot. So I set out some of the circumstances of the story: the setting, some of the characters, and some of the themes, and from that point on, it was a complete collaboration. We both feel that the script is a lot better than the film, as it finally turned out.

It took three years to raise the money for it, during which time I made MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING and worked at various editing jobs.

Was it your own idea to shoot GLEN AND RANDA in 16mm?

We did it to save money, but I was all for it. At the time, you had a lot more freedom shooting in 16, and like a lot of other filmmakers of the time, I thought of 16m in a political sense, as an alternative medium to the big studio way of doing things. As it turned out, we brought along 25mm equipment for the night scenes and for several of the long shots, and in retrospect, I think it might have been better to have done the whole thing in 35mm. The other two films could only have existed in 16mm.

How much of GLEN AND RANDA was improvised?

My original intention was to improvise a lot, but my two lead actors didn’t feel comfortable that way, and so most of their stuff was written. The Magician’s role was improvised a great deal by Garry Goodrow, who is a very literate veteran of The Committee. (3) Lorenzo returned to the set during the shooting of the last third of the film after an illness, and he and I would occasionally improvise a scene with Woody Chambliss. The most notable of these scenes were the one in which he brings Glen and Randa to the trailer for the first time, and the walk on the beach with Glen.

How would you relate GLEN AND RANDA to science fiction, or do you feel that it belongs to that genre?

I think of it as a science fiction film. Both Lorenzo and I are genre lovers, and like to use genres as points of departure for everything we do. GONE BEAVER started out to be Western, and THE BROTHERS FRIGIDAIRE was to be a spy musical.

That line about “Howie Hawks” in GLEN AND RANDA suggests that you conceive of the film as being “post-Hollywood”. To what extent do you consider Hollywood dead?

Well, whereas Hollywood in its heyday was filled with corrupt, talented people, now it’s filled with corrupt, untalented people.

Why did you decide to shoot most of GLEN AND RANDA in long and medium shots?

I believe that this was a mistake. I wanted the film to have a kind of ethnographic stance, one that stood outside of the action, as if one were observing the habits of wildlife or of an alien culture. Unfortunately, most people found it boring and uninvolving, and I regret that.

How closely did you stick to the scripts of DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY and GLEN AND RANDA while shooting?

There was no script for DAVID HOLZMAN; only a few notes to myself. But most of the time, I knew very clearly what I wanted to do. Of course, it changed a great deal during the shooting. The film was shot in snatches over a period of months, and sometimes, in periods of inactivity. I would get a new idea or discard an old one. GLEN AND RANDA was much more carefully scripted, but it changed a lot in the shooting too, most often because we’d find ourselves in situations where we couldn’t do what we wanted to do, and so we’d have to figure out something new. I’ve become convinced that one of the keys to making films is adaptability to circumstances. It’s a very hard thing to learn.

Some viewers have complained about the violations of certain naturalistic conventions in GLEN AND RANDA, e.g. the car in the tree, or Glen not knowing what a horse is, or the facts about pregnancy. It represents a real contrast, in any case, to the “naturalistic’ surfaces of your first two films.

We wanted GLEN AND RANDA very much to be a “naturalistic” film, that is, to try to show what life “really”m would be like in that setting. If we didn’t succeed, it was because we didn’t pay enough attention to detail.

Identifying and describing possessions is a central motif in all three of your films”: David Holzman showing off his film equipment and girlfriend, Clarissa detailing the contents of her purse (and you showing off Clarissa), the magician in GLEN AND RANDA displaying all his gadgets, and Glen identifying all the objects in the trailer. What kind of significance does this kind of cataloging have for you?

It’s a good way of finding out about someone. It’s like when you go into a person’s house for the first time, you look at his books or his records, or the things he has on his wall.

Except perhaps for the evening of TV in DAVID HOLZMAN (another catalog) (4) and the home movie at the end of MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING, montage always seems to play a secondary role in your films. Is this because, unlike some directors, you prefer shooting to editing?

I always had a secret predilection for montage, but I regarded it as having to do with the corny side of my character, and that it ought to be suppressed. I was also preoccupied with the idea of real time and the idea that montage was a very easily manipulative technique, and I was committed to a cinema that showed you things as against one that told you how to feel. I don’t know whether I believe that stuff any more.

Why do you show Randa eating bugs? It’s a scene that invariably makes spectators flinch.

The most commonly flinched-at scenes are the fish-killing and the butchering of the horse. I think that shocking people is a very good way of making them pay attention to your story. Also, I think it’s important for films to show aspects of life that one doesn’t encounter in his day to day experience.

What kinds of distribution and/or exposure have your films had?

I have a curious talent for signing up with distributors who go out of business shortly after they take me on. This has happened with five distributors in three countries that I can think of offhand, As a result, none of my films has been seen around very much. DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY has been to half a dozen festivals and a couple of dozen universities and museums. As I said before, MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING has only been seen at Cannes and a couple of other places. GLEN AND RANDA was released in several major cities in the U.S., but had a short and uneventful public life, after which that company went out of business. I have recently signed over DAVID HOLZMAN’S DIARY and MY GIRLFRIEND’S WEDDING to New Yorker films here in New York, and I have every confidence that they will go into bankruptcy any day now.

Could you describe the GONE BEAVER project, and give an account of what happened to it?

The GONE BEAVER project has a long and traumatic history that I won’t go into in any detail. I was approached by Bob Rafelson in the summer of 1971 to do a film for his company, BBS Productions. It was a very generous offer that included a great deal of freedom and artistic control. I wanted to do a film about Indians and mountain men, the wild men who trapped beaver in the Rocky Mountains before the West was settled. Lorenzo and I spent about a year researching the period and writing a treatment and two drafts of the script.

The central action of the film took place around a fort in the wilderness where trappers and Indians would come for semi-annual bacchanals to trade goods, get drunk, gamble, and get laid. The main characters were a mountain man named Coups Cooper; a young Crow Indian boy, who has a “vision”; an Austrian painter named Kurz, who works as a gatekeeper at the fort; and an Englishwoman named Annie, the mistress of a Lord who was killed in a skirmish with the Indians. The lives of these characters became intertwined in curious and complicated ways during the course of the story. I’m afraid that I can’t find a simple way to synopsize it. Everything went along quite well until I moved to Los Angeles to begin preproduction of the film. It then became clear that I wasn’t going to have anything like the freedom or control that had been promised me, and that in fact, the people I was assigned to work with at BBS had very different ideas from me about what this film was to be like and how it was to be made. Two major rewrites of the script were demanded, the budget and shooting schedule were cut almost in half, and I began to feel that I was being overruled on almost every question of importance. By the end of the preproduction period, a series of disasters forced us to move the production to another country. BBS insisted that we go to Canada, against my very strong objections, and when we got there it became immediately clear that we weren’t going to be able to pull it off. Many important people quit the production out of exasperation. There was a big confrontation with the producers (Rafelson was not involved at this point) in which I was told to direct the film according to their instructions “or else”. I took the “or else” and quit, and I haven’t worked since. A typical Hollywood story, in other words.

I understand they are talking about doing it again this year, with Dennis Hopper directing. I hope he chokes on it.

To some extent, your position in the American cinema seems to be directly in between Hollywood (the commercial cinema) and the Underground. Do you find this to be an advantage, disadvantage, neither, or both?

I think that you describe my position accurately. It’s a position in which I’d like to remain, but at the moment it’s a very disadvantageous one. All of the sources of financing for films like mine have dried up in the Nixon era, and the major studios control practically everything now.

What are the current developments in cinema (films, directors) that interest you the most?

wWe have two kids and very little money, so we don’t get out very much. We watch the old masterpieces of Hollywood on television. The only really interesting films I can recall seeing in the past year are THE HARDER THEY COME, QUATRE NUITS D’UN RÊVEUR, and FRENZY. I don’t get to see underground films very much, but I understand that Michael Snow and Hollis Frampton are very interesting. The only European films that get over here are of the Lelouch-Costa-Gavras variety, and I don’t like them much. All in all, it seems to me that we’re caught in some rather barren times.

A question nobody else asks: to what extent do you feel influenced by arts other than film? (Novels, plays, music, painting, etc.)

I used to be very much under the spell of the art scene, but my main influences were always other movies. I’m a great music lover and hope to use music more in future films than I have in the past, but I must confess that there doesn’t seem to be much going on in any of the arts, including movies, right now that titillates my interest.

Would you like to say anything about your new script?

It’s not a script yet; it’s a long treatment. It’s called THE BROTHERS FRIGIDAIRE, and it’s cheap, and terrific, and I hope that one of your readers would like to put up the money for it.

Footnotes:

1. Cf. the “screenplay” of the film — actually a description of the film written after the fact by L.M. Kit Carson, who plays David Holzman — published by Farrar, Straus & Giroux, New York, 1970.

2. Quoted in The Performing Self, by Richard Poirier, Oxford University Press, New York, 1971.

3. A satirical American cabaret group that uses a great deal of improvisation.

4. One of the more amusing sections of David’s diary is a record of an entire evening that he spends watching television, which lasts only a few moments on the screen (just over a minute, to be precise): each time a shot changes on the TV set, he clicks off one frame in his camera, recording 3,115 television images in all.