This review appeared originally in Cineaste, Fall 2001. — J.R.

Searching for John Ford

by Joseph McBride. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2001. 838 pp., illus, Hardcover: $40.00

Only sixty pages longer than his other lengthy biography, Frank Capra: The Catastrophe of Success (1992), Joseph McBride’s Searching For John Ford is, in fact, a very different sort of book, and not only because the size and importance of Ford’s work is considerably greater. The earlier volume — a devastating act of demystification that sought to dismantle not only a populist hero, but also the national mythology that virtually willed him into existence — made the value of Capra’s films appear almost secondary. It was suggested, moreover, by Gilberto Perez that McBride even seemed to gloat over the failure of Capra’s farm — that the author’s apparent animus toward his subject spilled over into his cultural critique. For me, the self-deluding aspects of Capracorn — in contradistinction to the erotic splendors of Capra’s best Thirties work — made such a relentless assault on the mythology both useful and necessary.

One might argue that Ford’s career, by contrast, is much too varied and complex to suit any such monolithic agenda, moral or otherwise. McBride’s desire to keep certain questions about the filmmaker open is evident in the book’s title, and in an overall tendency to avoid pat explanations. A couple of years ago, the Japanese film critic Shigehiko Hasumi made the provocative suggestion to me that Ford’s films seem to grow out of a trauma of some kind, making his work ripe for psychoanalysis. Perhaps that’s too simple a skeleton key to apply to such a huge filmography, yet the conflicts and contradictions running through the Fordian oeuvre are hard to deny — as are the almost equally constant (and therefore telling) denials of artistic intent and solitude. Far from being a happy family man, Ford seemed ‘at home’ mainly while drinking with members of his stock company, and McBride depicts him as a profoundly lonely person whose acts of bullying sadism against his cronies reflected various fears and feelings of inadequacy.

McBride’s book finds these conflicts, contradictions, and denials everywhere, and the graceful way he integrates his sense of the life with his critical reading of the films is this biography’s soundest achievement. This achieves a certain apotheosis in the following two sentences, found on page 303 — perhaps the most useful thumbnail account of Ford’s art that we have: “The cherishing of a momentary image, immutable in its delicacy and precision of framing, begins to assume obsessive proportions as shot after shot rolls inexorably away. It is as if the very perfection of the image is the cause of its transience.”

Most previous writing on Ford has been hamstrung by opting for either ideological attack or ideological defense and then becoming entrenched in that one-eyed position. McBride, by refreshing contrast, has the good sense to perceive that The Searchers is a racist film that also has profound and objective things to say about racism — sometimes in alternation and sometimes even simultaneously. (Much the same applies to the similarly obsessed William Faulkner; it’s astonishing to reflect that only three years separate Sartoris from Light in August — just as the crude comic use of a squaw named Look in The Searchers exists alongside the highly complex and nuanced treatment of John Wayne’s Ethan Edwards.)

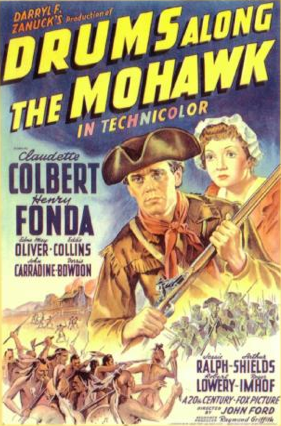

It’s significant that Ford assigned Duke Morrison — the future John Wayne, then working as Ford’s prop man — the job of Stepin Fetchit’s dresser on Salute, a 1929 feature shot in Annapolis, and that Ford saw to it that the black actor stayed in the commandant’s guest house. Furthermore, according to McBride, “It’s no exaggeration to say that Woody Strode, another black actor, was the last great love of John Ford’s life” thirty-odd years later. But it’s no less significant that Ford was probably anti-Semitic and, according to McBride, bore some responsibility for encouraging the incarceration of Japanese Americans in concentration camps during WWII. And when it came to Native Americans, ambivalence bordered on schizophrenia. McBride provides detailed documentation on Ford’s affection for Indians who acted in his films as well as his penchant for depicting them as “murderous savages” in such films as Drums Along the Mohawk and Rio Grande — and his indifference to casting them in the right tribes, analogous to his treating the Welsh as if they were Irish in How Green Was My Valley. He also cites some hilarious evidence that some Navajos took revenge for such treatment by ad-libbing on-screen non-sequiturs and wisecracks in their native tongue.

“Ford was terrific!,” his Jewish friend Samuel Fuller once said. “He wore a chain around his neck, under his shirt. If he was talking to a Catholic, he pulled out his cross. If he was talking to a Jew, he would pull out his Star of David…He had the full panoply.” This chameleonlike quality may have extended to his politics above and beyond his gradual evolution from left to right: “No doubt Ford would not have remained commercially viable for so long,” McBride plausibly speculates, “if he had not been simultaneously reactionary and progressive.” The man who opposed as well as supported the Hollywood Blacklist during the same period ran the political gamut as fully as his contemporary Kenji Mizoguchi did, and it appears that the reasons were not merely opportunistic but conflicts in his character.

On page 201 of the bound galleys of Searching For John Ford, McBride provided a short list of Ford’s greatest films that he chose to omit in the finished book. I can understand this decision because such a list may oversimplify the book’s critical positions, so I hope the author will forgive me for reproducing it here in the interest of indicating some of his priorities — Pilgrimage, They Were Expendable, Wagon Master, The Quiet Man, The Sun Shines Bright, The Searchers, The Man Who Shot Liberty Valance, and 7 Women. (McBride adds that others might cite, with equal validity, Young Mr. Lincoln, The Grapes of Wrath, and the dance at the church dedication in My Darling Clementine.) It’s a list as notable for its omissions (Stagecoach, How Green Was My Valley, the Cavalry trilogy) as for its inclusions, and though anyone could pick bones with it — I personally prefer Judge Priest to The Sun Shines Bright [2019: or at least did when I wrote this review] — it seems clear that McBride isn’t interested in overturning apple carts, as he was in the Capra biography.

Given the thoroughness of the research, one regrets occasional lapses in the writing. When we learn that Rear Admiral John D. Bulkeley “refused Ford’s offer to serve as a technical adviser on They Were Expendable,” “invitation” is what’s meant by “offer,” because it wasn’t Ford offering his services to Bulkeley. There’s a memorable quote from Jean-Luc Godard that McBride copies from the seminal Ford study he wrote with Michael Wilmington in the early Seventies: “Mystery and fascination of this American cinema…How can I hate John Wayne upholding Goldwater and yet love him tenderly when abruptly he takes Natalie Wood into his arms in the last reel of The Searchers?” Both citations of this awkward translation silently and perhaps unconsciously correct Godard’s error that this happened in the next-to-last reel (meanwhile omitting references to Robert McNamara and Take the High Ground as well as the fact that this reflection was inspired by reseeing Fallen Angel — a good example of the sort of things that routinely get lost to film history).

But this is quibbling. Searching for John Ford is not only critical biography of the first order, but an invaluable guidebook to the mystery and fascination of John Ford.