From Film Quarterly, Spring 1984. -– J.R.

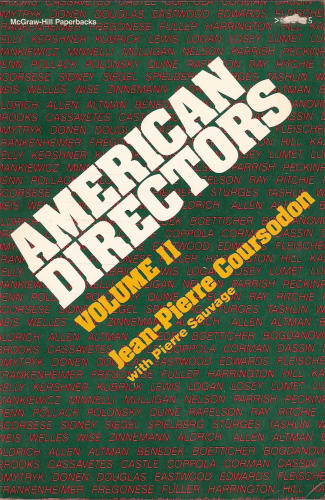

AMERICAN DIRECTORS

Two volumes. Edited by Jean-Pierre Coursodon, with Pierre Sauvage. New York: McGraw Hill, 1983. $21.95 per volume cloth, $11.95 per volume paper.

On the whole, Jean-Pierre Coursodon’s 874-page, two-volume American Directors is closer in genre to Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary than it is to Andrew Sarris’s The American Cinema. Like both predecessors, it is an encyclopedia of opinions first and facts second — although, to its credit, it has many more facts per entry (in filmographies and career summaries) than either of the earlier monoliths. Like the Roud and unlike the Sarris, it attempts exhaustive surveys rather than suggestive critical miniatures, and is authored by many hands. Coursodon wrote 66 of the 118 essays and co-editor Pierre Sauvage, who furnished all the filmographies, contributed 13; the remaining 39 are by 20 other writers.

Again like the Roud, the Coursodon stands or falls as a compendium more than as a book with a sustained viewpoint; consecutive or continuous reading is neither recommended nor viable. Overall, the criticism is homogeneous, perhaps too much so: the standard auteurist form of career survey — already a bit fossilized — as developed out of Coursodon and Bertrand Tavernier’s Trente ans de cinéma américain (1970) and The American Cinema (1968) is so predominant here that other critical persuasions of the past two decades might as well have never existed. On the other hand, the critical frame of reference adopted by Coursodon and Sauvage is much wider than Sarris’s by virtue of being more truly bilingual. Even if Kael gets four times as many citations in the index as Bazin (while Bellour, Fieschi and Heath get predictably none), French appreciation of American cinema is basic to the underpinnings of the subject, making this collection an ideal starting place for Americans who wish to learn more about the French enthusiasm for Tay Garnett, Jerry Lewis, Frank Tashlin and Don Weis (among others) in English. The fact that Coursodon winds up being somewhat equivocal about all four is characteristic, but it is precisely this balanced ambivalence that makes him an excellent mediator. A specialist in Hollywood comedy, Coursodon makes an unexpected, noble defense of Woody Allen’s Stardust Memories — a lot more interesting to read than all the predictable hatchet-jobs — and comes down hard on Chaplin’s A Countess from Hong Kong no less persuasively, with particular emphasis on the continuity errors. The other French contributors are four able critics largely identified with Positif: Jean-Loup Bourget, Michael Henry, Alain Masson and Yann Tobin.

The remaining writers vary widely in effectiveness, although all tend to come across as competent. Ronnie Scheib’s study of Ida Lupino is so strong that one regrets that she didn’t contribute more to the collection; the chapter on Coppola by Diane Jacobs, the only other female contributor, regrettably doesn’t extend beyond Apocalvpse Now. Other pieces break down for me on individual caveats: in the essays on Budd Boetticher by Barry Gillam and William Wellman by Todd McCarthy, both otherwise respectable surveys, the two most experimental (and, to my mind, most interesting and effective) films by each director — A Time for Dying (1969) and Track of the Cat (1954), respectively — aren’t even discussed. Myron Meisel is perceptive about John Cassavetes in general, but misses the extent to which the closing reel of The Killing of a Chinese Bookie encapsulates the director’s personal testament (above all, in the use of “l Can’t Give You Anything But Love” in the nightclub). In his Michael Ritchie entry, Mark LeFanu just about wins me over when he relates Smile to Ibsen, but strains my credulity when he compares Semi-Tough to Makavejev.

It’s in many of the shorter entries that the auteurist method seems most questionable; reliable deadwood facts and measurements tend to accumulate, often to little purpose. The first sentence by Pierre Sauvage on Norman Z. McLcod doesn’t exactly compel one to read further: “In the course of a career devoted primarily to comedy and secondarily to musical comedy, Norman Z. McLeod, whose manner on movie sets was soft- spoken and unassuming, seems to have displayed little more than modest if occasionally serviceable craftsmanship.” A similar aim seems to be behind much of the critical writing, with mixed results. One can only speculate over the system of inclusion that makes way for dutiful term papers on such directors as McLeod, Lloyd Bacon, Edward L. Cahn, Jack Conway, Gordon Douglas, Norman Foster, Hugo Fregonese, Stuart Heisler and Vincent Sherman, while excluding such diverse figures as René Clair, Monte Hellman, Dennis Hopper, Phil Karlson, Albert Lewin, Elaine May, Max Ophüls, Jean Renoir and James Whale.

The overall virtue that most of the contributors successfully strive for is judiciousness — a quality that especially characterizes David Sterritt on Robert Altman, John Belton on Robert Mulligan and Edgar G. Ulmer, Roger McNiven on Gregory La Cava and Jacques Tourneur, and Charles Wolfe on Busby Berkeley, Cecil B. De Mille and Mervyn LeRoy. It is the sort of reasonableness that one commonly associates with Positif rather than Cahiers du Cinéma, and relative Cahiersists like myself may regret the relative absence of passionate hyperbole and delirium (LeFanu on Ritchie is a rare exception) that aims at polemics more than straight assessments. The problem is merely one of temperament, and other readers may value and even cherish American Directors precisely for some of those sturdy reasons that make me respect it more than enjoy it. Insofar as commonsensical critical judgments rather than provocations or challenges are the main bill of fare, this hefty work avoids the eclecticism of Roud’s Critical Dictionary as well as the aphoristic bravado of early Sarris to settle on a steady, classic diet of meat and potatoes, served with dependable regularity. Students of the subject could do far worse: determined aesthetes may want to look further. — JONATHAN ROSENBAUM