From the August 29, 1997 Chicago Reader. This is one of the 13 pieces selected and translated into Farsi by Saeed Khamoush for the unauthorized collection of some of my Reader pieces that was published in Iran back in 2001, and the only one in that volume relating to Iranian cinema. — J.R.

Gabbeh

Rating *** A must see

Directed and written by Mohsen Makhmalbaf

With Shaghayegh Djodat, Abbas Sayahi, Hossein Moharami, and Roghieh Moharami.

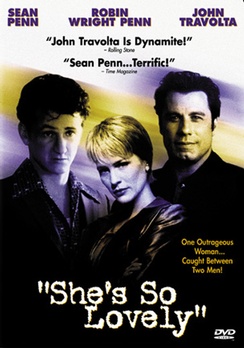

She’s So Lovely

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Nick Cassavetes

Written by John Cassavetes

With Sean Penn, Robin Wright Penn, John Travolta, Harry Dean Stanton, Debi Mazar, Gena Rowlands, and James Gandolfini.

To put it in simple market terms, Gabbeh packages Iran and She’s So Lovely packages John Cassavetes. Both films succeed admirably in taking on intractable and potentially uncommercial material — at least from the standpoint of mainstream Western audiences — and in making an alluring consumer object out of that encounter. Both take ideological shortcuts to make this alchemy possible, and that limits their artistic and expressive range, though this seems unavoidable given the marketplace barriers they’re bent on overcoming. The problem is in learning how to appreciate them for what they are without losing sight of what they aren’t.

Gabbeh was shot in Iran by one of the greatest Iranian filmmakers and has enjoyed immense commercial success at home, especially as an art film. She’s So Lovely is based on a script by the late John Cassavetes, directed by his son Nick and starring the same actor, Sean Penn, Cassavetes originally approached for the lead part. Both movies are sincere rather than cynical efforts. Why then should anyone question their credentials?

For starters, consider a couple of crucial points: Gabbeh is a film for tourists made by another tourist, and She’s So Lovely is a Hollywood studio version of a script by an American independent. I’m sure Mohsen Makhmalbaf realizes he’s a tourist, based on things he’s said about Gabbeh, but I’m less sure that Nick Cassavetes realizes he’s made a studio picture. Maybe that’s because Makhmalbaf has the advantage of living in a society where artists are revered. Some of his films get shown in Iran, and some of them don’t –but to the best of my knowledge he’s had the final cut on every one. The same is true of all the pictures John Cassavetes acknowledged as his own (he paid dearly for this freedom, as did Orson Welles on his nonstudio productions), but not of those of Nick Cassavetes — who has the disadvantage of living in a society where producers are revered more than artists.

She’s So Lovely is Nick Cassavetes’s second feature (Unhook the Stars was the first). The original script was written in 1980 by his father, who completely rewrote it in November 1987 — 14 months before his death — when he was considering Sean Penn as the lead. This information comes from a book about Cassavetes by Thierry Jousse, and it’s symptomatic of Cassavetes’s American reputation that such data can’t be found in the only two American books about him, both by Ray Carney. Carney offers a lot of heavy breathing about Cassavetes’s relation to American transcendentalists and Frank Capra, but for concrete facts and stylistic intuitions about his work you have to go to the indispensable, passionate writings of Nicole Brenez (her recent book about Shadows and some scattered articles, all in French) and Jousse’s useful monograph (also in French).

The title of the script is She’s Delovely, after the Cole Porter song “It’s De-Lovely,” which is heard at one point in the action (the fees the Porter estate demanded persuaded the film’s producers that they could afford to use only the tune). It stems from a key line of dialogue, spoken by Penn in the final scene — a choice example of irrational Cassavetes wordplay: “She doesn’t love you. She doesn’t love me. She’s… delovely.”

The most interesting thing about the film is the unique access it provides to the original script (presumably the 1987 version). It is, after all, a kind of companion piece to A Woman Under the Influence (1974), and the only John Cassavetes project I’m aware of that combines the working-class milieu of A Woman Under the Influence with the middle-class suburban milieu of Faces (1968). A devoted working-class couple in an unnamed industrial city, Eddie and Maureen (Sean Penn and Robin Wright Penn, a real-life married couple) undergo a crisis after Eddie returns from a few days’ absence to find Maureen, who’s pregnant with their first child, battered and bruised. We’ve already witnessed the cause of her injuries — a drunken altercation with a boorish neighbor (James Gandolfini) in their dingy rooming house — but Maureen, terrified of Eddie’s rages, invents an excuse about falling down in the street. When he discovers the truth, Eddie goes on a raving, murderous binge, shoots an orderly who attempts to restrain him, and winds up incarcerated in a mental asylum for a decade.

Ten years later we find Maureen married to Joey (John Travolta), who runs a construction company and seems to have a gangster background, and living in the suburbs with their three little girls (the oldest fathered by Eddie). Eddie emerges from the asylum and, with a little help from two old friends (Harry Dean Stanton and Debi Mazar), resolves to reclaim his former wife. (Both Maureen and Eddie have changed the color of their hair — Maureen’s gone from blond to black, Eddie from black to blond — and I wonder if this detail was in the original script.)

As in many Cassavetes scripts, the plot is as full of holes as a Swiss cheese sandwich. We never have a clue about what Eddie and Maureen do for a living in the first part, and Maureen’s refusal to visit Eddie during his incarceration is simply a dramatic device — as improbable as the refusal of Gena Rowlands’s husband and kids to visit her when she’s locked away for six months in A Woman Under the Influence. To make matters worse, the script asks us to believe that after Eddie’s declared sane again (by Rowlands, playing a psychiatrist) he thinks he’s been out of circulation for only three months. (When Maureen had him committed ten years before, she told him she thought he could become well enough to leave in three months.)

Nonnaturalistic and irrational elements of this kind tend to be standard in John Cassavetes’s features, yet the films live and breathe in spite of them — perhaps even because of them, insofar as they help to establish some of the directorial and acting flourishes. But here — where the visual style, editing, and background music are much less personal and far more conventional, including a ‘Scope format (unthinkable in a John Cassavetes feature), standard continuity editing, and brassy wall-to-wall music for “punch” — such elements figure more as flaws or eccentric cadenzas that carry some of the Cassavetes flavor but none of the texture or substance. The theme of love, which John Cassavetes labeled the only concern of his work, certainly takes center stage. But the conclusion of this movie reminds me of The Graduate, and I find it impossible to believe that I would feel that way if Nick’s father had been in control.

This isn’t to say that the film isn’t entertaining — it is fun, but it doesn’t stick. It comes to life mainly in its second part — above all thanks to Travolta, who imparts a witty and embattled humanity to his character that offers some relief from the compulsive method tics of the Penns and who doesn’t even seem out of place in the script’s demented schemes. (Whatever else the Penns have, they don’t have much flair for comedy, at least under Nick Cassavetes’s direction; Sean’s habitual expression, which makes him appear to have just bitten into a lemon, has none of the peaks and valleys of Travolta’s grimaces, while Robin’s slightly larger repertoire, abetted somewhat by her character’s upward mobility, usually consists of variations on the same reflexes of denial.) But the whole thing still boils down to a studio version of an unruly maverick script, where most of the enduring mysteries of the Cassavetes oeuvre are flattened, rationalized into simple gags and routines.

On one level She’s So Lovely remains a contribution, however modest, to John Cassavetes’s oeuvre. Yet if we consider all the things that work against that contribution — and that the results are packaged with the brand name “Cassavetes” anyway — we’re bound to feel that something’s missing. In a valiant attempt to cope with this problem the distributor, Miramax, recently arranged to screen half a dozen John Cassavetes films in New York and Los Angeles, three of them in newly struck prints; commissioned a monograph (mainly by Carney); and got Film Comment magazine to host panel discussions on his work in both cities as well. (It’s a prime example of big business stepping in to fill the void left by the evisceration of state arts funding, much as Barnes & Noble and Borders are assuming the community roles once played by public libraries.) But Chicago won’t be getting these sidebars, so the task of putting She’s So Lovely in context falls to the local press.

How far has Nick Cassavetes honored the original script? When I asked him about this at his press conference at Cannes he admitted that he didn’t understand certain things in the script (he didn’t specify what), and so he simply eliminated those parts. I can’t reproach him for this — scripts are blueprints, and nothing is gained by treating them like holy writ. But I still become queasy when the results are peddled as “a film by Nick Cassavetes” based on “a romantic parable by John Cassavetes” — especially when neither Cassavetes wound up with the final cut. It’s not clear to me who did, though it hardly seems to matter: eight producers are listed in the credits, including Sean Penn and Travolta, Gerard Depardieu, Miramax’s Weinstein brothers, and two or three others associated with the French company Hachette Premiere. The fact that Hachette is currently suing Miramax for unfulfilled payments and has tried to block the film’s release as a consequence only adds to the confusion about who did what to whom. John and Nick Cassavetes and the actors all qualify as meat and vegetables in this stew, but I suspect the chef is a process rather than an individual — a process that has more to do with business than with art. Do you want your Cassavetes half-baked or stewed? I prefer mine raw.

The task of packaging Iran, something infinitely more complex than John Cassavetes, for the international market borders on the quixotic, but Mohsen Makhmalbaf seems to have known precisely what he was up to when he made Gabbeh. A gabbeh is a kind of Iranian carpet produced by the nomadic Ghashghai tribe and compared by some people to American quilts as a form of folk art. Makhmalbaf estimates that only one out of every ten thousand Iranians owns a gabbeh and that only one out of every thousand has even heard of one. But as a luxury item that can appeal to the imagination, stimulate an aura of fairy tales, and summon up a preindustrial idea of Iran that can fit cozily inside any Westerner’s home, the gabbeh is a consumer object, Disney cartoon feature, and visionary art-movie icon all rolled into one.

“I think gabbehs are like good Iranian films,” Makhmalbaf has said. “What attracts foreign audiences to Iranian films is their simplicity and their re-creation of nature. These are the same two qualities that have made gabbehs popular in foreign markets as well. In Western countries people are overwhelmed by difficult, complicated, and rough situations. When they go to the movies they don’t want to see the same complexity and violence they are surrounded by. That is why they are fascinated by simple Iranian films that remind them of nature. Iranian gabbehs also have a sort of naturalistic poetry about them that gives you a sense of tranquillity. You feel that you have spread nature on the floor of your living room.”

This sounds delicious, and Gabbeh is nothing if not ravishing in terms of colors, landscapes, sounds, and fairy-tale evocations. Since it premiered in Cannes last year, I’ve seen it at least four times, each time without being able to follow every twist in its dreamy, multilayered plot, but I’ve never felt frustrated as a consequence. The film offers a treasure chest; it’s only after you total up the booty inside — assuming you consider this worth the trouble — that the contents seem meager.

In the opening shot a multicolored gabbeh floats down a bubbling mountain stream, and then we see water rushing past the interwoven figures on it as the carpet remains stationary — a woman in blue and a man in red riding together on a white horse. Before long, a real (or symbolic) woman in blue named Gabbeh (Shaghayegh Djodat) appears and smiles at the camera, then a quarreling old couple (Hossein and Roghieh Moharami, another real-life couple) in a mountain-filled landscape prepare to wash a gabbeh. This casual interchange between various levels of representation — figures in a carpet, a figure from a carpet, a carpet in a stream, carpet weavers in a landscape (with the old wife wearing a blue dress identical to Gabbeh’s), following one another like rhymes — gradually evolves into a story about Gabbeh, a young woman in love with a mysterious horseman who follows her nomadic clan at a distance.

Though Gabbeh’s father theoretically consents to her marrying this stranger, who howls for her in the night like a wolf, he stipulates that her uncle (Abbas Sayahi), who arrives from the city, has to find a wife first. After this finally happens, her father says she must wait for her mother to give birth again. Prefacing most of this story is a lecture by the uncle about the colors of nature, illustrated by magical-realist details that eventually become woven like colored threads into the story itself.

Originally planned as a documentary for the Iranian Handicraft Industries Organization to be shot in southeastern Iran — the same general area where Merian C. Cooper and Ernest B. Schoedsack, the future makers of King Kong, shot their silent 1925 documentary Grass — Gabbeh quickly turned into a fiction film once Makhmalbaf enlisted villagers to play the nomads and reenact a Ghashghai migration. He had plastic flowers planted in the backgrounds of certain shots, designed some of the gabbehs himself, and didn’t hesitate to make the migrations look more primitive than they actually are, with the tribespeople traveling on foot and horseback rather than in trucks. (In this respect he recalls some of the methods of Cooper and Schoedsack’s ethnographic contemporary Robert Flaherty in such early films as Nanook of the North and Moana — though Flaherty, unlike Makhmalbaf, didn’t resort to using actors in the same fashion.)

The landscapes, vistas, and visual details that emerge from this fanciful folklore recall images that we associate with “Russian” cinema (a misnomer from a postcommunist vantage point) — the huge skies and wind-rippled fields of the Ukrainian Alexander Dovzhenko and the manufacture of dyes and primitive tableaux shown in The Color of Pomegranates by the Armenian Sergei Paradjanov. But the differences in Makhmalbaf’s relationship to his material are crucial. Dovzhenko created an exalted poetry out of his own ethnic traditions, and Paradjanov did something nearly comparable at one remove. But city-born Makhmalbaf eyes his material from at least two or three removes; far from delving into his own folklore or that of his ancestors, he’s much closer to Nicholas Ray making a film about Eskimos in The Savage Innocents (1959) — fashioning a “universal” parable out of semiexotic materials.

This doesn’t make Makhmalbaf’s project illegitimate, but it does limit his credentials as a natural bard. He’s vastly superior in this respect to the animators of the Disney Aladdin, but next to Dovzhenko or Paradjanov he’s something of a dilettante. This is arguably even his strength as a filmmaker, given that he’s a heroic experimenter and explorer of his own divided consciousness. From Fleeing From Evil to God (1983) to Boycott (1985) to The Peddler (1987) to Marriage of the Blessed (1989) to A Time of Love (1991) to A Moment of Innocence (1996), no two Makhmalbaf films are alike; and if Gabbeh is another feather in his cap, it’s at once a more picturesque and a less personal one.

Similar qualms might be expressed about his handling of landscapes, stunning as many of these images are. Where his compatriot Abbas Kiarostami films landscapes as if they were architecture — integral spaces that are intimately lived in — Makhmalbaf films them as if they were sculpture, “found” aesthetic objects designed for contemplation. Like the gabbehs themselves, these landscapes are set before us like consumer products, to be admired more than entered and investigated. Even the feminist implications of Makhmalbaf’s tale are protected by the nonspecific workings of the patriarchy that give rise to those implications. Within this parable women suffer and bear the burden of family responsibilities that thwart their own desires, but what keeps them in their place remains as elusive and sketchily defined as the mysterious horseman trailing the nomads — or as Gabbeh’s father, for that matter.

This is why one can argue that Gabbeh packages not so much Iran as a travel-poster, fairy-tale substitute for that country. By contrast, Jafar Panahi’s The White Balloon, the only other Iranian art film to receive U.S. distribution, is set in contemporary Tehran, though it offers the viewpoint of a little girl as a safeguard against having to explore the complexities of that world from an adult viewpoint. From the vantage point of the mainstream marketplace, contemporary Iran appears to be as intractable and threatening as a film by John Cassavetes, so it needs to be boiled down to something simpler and more timeless. Once again a romantic parable seems to do the trick.