From The Soho News (November 24, 1981). — J.R.

Nick’s Movies (Nicholas Ray retrospective)

The Public Theater through December 13

Fantasy and counter-fantasy are perpetually at war in the films of Nicholas Ray — accounting in no small measure for the highly charged heat, light, fury, beauty, and pain that most of them project. In its most brilliant representations — the separate divisions of Vienna’s saloon in Johnny Guitar (1954), an almost surrealist Western; the house and mind of Ed Avery in Bigger Than Life (1956), an almost expressionist domestic melodrama — this graphic warfare actually becomes expressed in terms of discrete zones of action and confinement. “Down there I sell whisky and cards,” announces the imperious Vienna (Joan Crawford) on a stairway, gun in hand, to an itchy search party below that’s somewhere between a lynch mob and a sheriff’s posse. “All you can get up these stairs is a bullet in the head.”

Or consider another scene, one of the most memorable jaded love duets in movies, again spelled out through architecture and spatial balances as well as words and faces. Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden) sits at a kitchen table, drink in hand, while Vienna stands behind him, on the other side of a serving window, also facing us. “Lie to me,” he says morosely. “Tell me that all these years you’ve waited for me.” “All these years I’ve waited for you,” she chants back at him in the semidarkness, and they continue this poker-face, blank-verse exchange — a song of lament that Godard wound up imitating in his second feature, Le petit soldat.

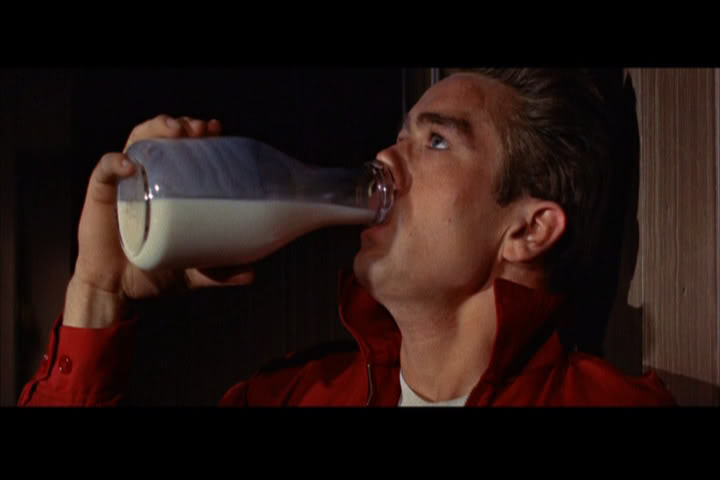

Fantasy and counterfantasy — a configuration assuming the shape of our own psychosexual, familial hangups in the 50s (and now), becoming an abstract expressionist roadmap, in a way, of our delirious imaginations and troubled politics. (If Ray has a directorial disciple working in America now, this may well be Dennis Hopper — whose Out of the Blue, shown at the Museum of Modern Art last summer, seems as Raylike in its preoccupations as The Last Movie.) The madness of Ed Avery (James Mason), the schoolteacher protagonist of Bigger Than Life — ostensibly yet inessentially linked by the plot to his use of cortisone — is the madness of America writ large, which becomes the madness of Hollywood, too: the insatiable hunger for the unattainable implied in the title that underwrites the mise en scène of our gaudiest self-projections.

Despite (or maybe because of) its romanticism, Ray’s cinema is in part a catalogue of Horrible Truths. One of the horrible truths of Bigger Than Life isn’t far from that of The Shining and Mommie Dearest (the latter another treatise on the madness of Hollywood) — that parents sometimes want to kill their offspring. As Number One Neurotic among Hollywood directors of the late 40s and 50s — who embarked on filmmaking at age 36 only after studying architecture with Frank Lloyd Wright and working in theater (with Elia Kazan), radio (with John Houseman, folk-song musicology (with Alan Lomax), and even as an administrator for the Office of War Information during World War II (where he reportedly gave painter and film critic Manny Farber his first job, as a toy “rejuvenator”) — Ray yearns after normalcy with an intensity that crackles and burns through his movies.

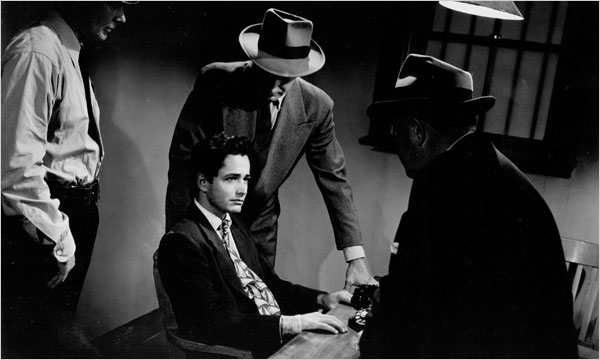

In his first film (and one of his best), They Live By Night (1948), the note of instability is set in the opening shots, behind the credits — the first helicopter shots in the history of cinema, which follow a runaway car (and later careen past a bigger-than-life billboard). This disequilibrium is maintained throughout by what can only be called an erotic handling of domesticity, which make a teenage couple’s efforts at settling down fragment into a scrapbook of fleeting instants. (Robert Altman’s remake of this movie, the 1974 Thieves Like Us, caught a little of the same quality.) The same kind of tension relating to the unachieved family runs like a live wire through Ray’s work, providing many of the strongest jolts.

If, in the earlier work, a life of crime (or, in the 1952 On Dangerous Ground, an equally brutal life of law enforcement) makes a family’s or even a couple’s security impossible, this dilemma becomes internalized in the domestic settings of Rebel Without a Cause and Bigger Than Life, where the family becomes eroded and threatened from within. Ed Avery, a normal man who dreams himself into the position of genius and sage reverses the predicament of Dixon Steele (Humphrey Bogart), the semiautobiographical scriptwriter hero of In a Lonely Place (1950) — an eccentric who tries to dream himself into a counterfantasy of normality. Or maybe it’s the same predicament, but seen through a mirror.

Derrière le miroir, the French release title of Bigger Than Life, translates as “behind the mirror”. And this shocking portrayal of Middle America losing its soul is, above all, a movie about looking into a mirror — another crucial link with Mommie Dearest, not to mention Raging Bull. So it stands to reason that a key vertiginous moment occurs when the door of a medicine chest is angrily slammed by Ed’s wife, and Ed’s reflected face — which was just a moment ago posing and preening itself, Hollywood-style, in a seamless image — becomes fragmented into a broken mosaic. And the radical multi-image format of We Can’t Go Home Again — shot with Ray’s students at the State University of New York at Binghamton in the early 70s, and intermittently edited by Ray until his death in ’79 — can be seen as the consequence of an analogous angry explosion, ignited in part by the 60s.

***

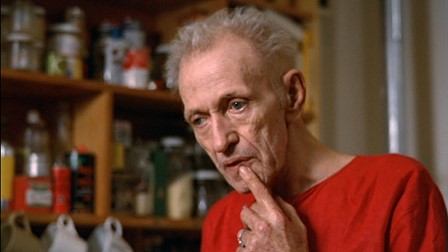

Why is the best and fullest presentation of Ray’s work that New York has ever seen (or is ever likely to see) being steadily ignored by most of the local media? On hand in the Public’s massive retrospective are newly struck 35mm prints of nearly all of Ray’s CinemaScope films — Rebel Without a Cause, Bigger Than Life, The True Story of Jesse James, Bitter Victory, and Party Girl — and at least three others (In a Lonely Place, Knock on Any Door, Wind Across the Everglades), plus old 35mm and 16mm prints of practically everything else. (Whether or not the major The Savage Innocents and the minor Run For Cover will be included is still pending as this article goes to press; check with the Public for future developments. Otherwise, the only missing Ray feature is the second and most negligible, the anonymous A Woman’s Secret.) Also included are regular screenings of Wim Wenders’ and Ray’s Lightning Over Water and, next month, the theatrical premiere of We Can’t Go Home Again.

Could the lack of response to this ambitious season be construed, at least partially, as fallout from the fear and confusion stirred up by Lightning and its associations with death? I suspect so. For this reason, I especially regret the absence from the retrospective of I’m a Stranger Here Myself (1974), a feature-length documentary about Ray that might have served as a possible bridge between Ray’s Hollywood work and the more radical presuppositions of We Can’t Go Home Again and Lightning.

As things stand, it appears that certain New York critics and other innocents have been responding to Lightning tribally, as if it were a sacred taboo — which saves them the bother of having to respond to it morally, aesthetically, or philosophically. The fantasies and counterfantasies of Wenders and Ray thus breed still more counterfantasies in the minds of some critics, motivated less by the film itself than by their fear of death. Could this help to explain the curious recent behavior of Stuart Byron in the [Village] Voice, who jocularly suggested that Wenders was a murderer — a charge couched in terms of a lit-crit pirouette that we’re all supposed to find amusing?

***

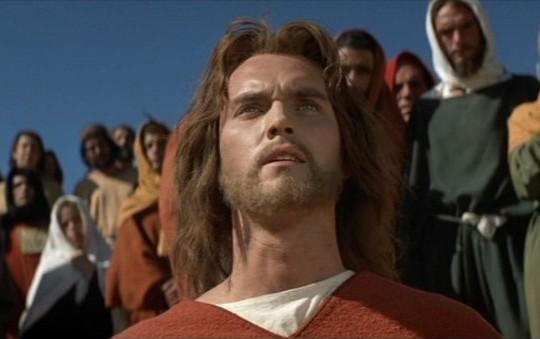

Ray’s work as a whole, like that of most romantics, is pretty uneven. I’ve never been able to work up much enthusiasm for Knock on Any Door, Flying Leathernecks, Run for Cover, The True Story of Jesse James, King of Kings, or 55 Days at Peking. (One finds flashes, though. There’s a neat Brechtian lesson in anarchist economics in the Jesse James film, when the title hero pays off a sweet old lady’s mortgage with stolen money, and then steals it back again from her landlord a moment later.)

By contrast, The Lusty Men, Bitter Victory, Party Girl, Wind Across the Everglades, The Savage Innocents, and even the often silly Hot Blood — the closest thing Ray ever came to doing a musical, with Cornel Wilde and Jane Russell as volatile gypsies — all have something crazed, flawed, and magnificent about them; and Rebel Without a Cause, for all its intricate datedness, still has its moments. (If memory serves, Born to Be Bad is interesting in a minor, caustic way.) The splashy colors and characters of Johnny Guitar are among the pivotal joys in American movies. And the enduring love between a beautiful dancer (Cyd Charisse) and a crippled, crooked lawyer (Robert Taylor) in the voluptuous Party Girl (1958), threatened by an evil 20s Chicago gangster named Rico Angelo (Lee J. Cobb) with a vial of acid, is a lush fairy tale delineated in Metrocolor and CinemaScope’s finest equivalents to bold strokes and purple prose.

“The subject of Ray’s films is not so much rebellion as the impossibility of rebellion,” Serge Daney wrote last year, “the perpetual dispute between two men, one young and one old, one the adopted and one the adopter.” Daney singled out two key lines of dialogue in Ray films to represent the poles of this recurring conflict: “I kill the living and I save the dead,” Richard Burton’s hopeless line in Bitter Victory (1957), stands for the son’s tortured impasse, while James Mason’s anguished conclusion in Bigger Than Life that “God was wrong” — for staying the murderous hand of Abraham against Isaac — encapsulates the mad father’s rage. Sometimes in the midst of all these wild fantasies and counterfantasies burns a constant, lurid light, tarnished but unrelenting, a little bit like Baudelaire; and the best of Nick Ray’s movies somehow keeps it going.