From the Chicago Reader (July 20, 1990). — J.R.

JESUS OF MONTREAL

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Denys Arcand

With Lothaire Bluteau, Catherine Wilkening, Johanne-Marie Tremblay, Remy Girard, Robert Lepage, Gilles Pelletier, Yves Jacques, and Arcand.

It must have been about 30 years ago that I saw Jules Dassin’s He Who Must Die, a popular art-house movie at the time and one of my first foreign films. Dassin, an American expatriate chased to Europe by the Hollywood blacklist, was a highly skilled film noir director whose best efforts included The Naked City, Thieves’ Highway, and Night and the City. He Who Must Die, set on Crete in 1921, was a French picture based on Nikos Kazantzakis’s novel The Greek Passion, concerning the performers in a passion play whose theatrical roles take over their real lives as they suffer from Turkish oppression; the theme was that if Christ came back today, he would be crucified all over again.

I was a teenager at the time, and being none too versed in what was considered sophisticated in film in 1959, I was moved to tears. This was at a time when the French New Wave had barely made a ripple in the American consciousness, and shortly before Dassin’s film was ridiculed by critics I admired, like Pauline Kael and Dwight Macdonald, as the acme of arty pretension. Those critics must have done a good job, because He Who Must Die seems to have vanished completely from sight in the ensuing decades. Whether or not Macdonald’s terse verdict (“a pretentious pastiche of Eisenstein-cum-socialist realism”) was just, I must confess that the weight of his and Kael’s and Andrew Sarris’s scorn has stayed with me more than most of the film has. So much so that whenever I hear about a similar film — anything that involves Jesus reappearing in the 20th century and being recrucified — I automatically cringe.

I avoided Jesus of Montreal at the Toronto film festival last fall, and I wasn’t looking forward to seeing it when it finally got to Chicago this summer. (The fact that foreign-language films now commonly take a year or more to reach our theaters seems to be largely the result of big-studio imperialism — the cultural mandate that we see without delay, for instance, the infantile proto-fascist ravings of Andrew Dice Clay.) I knew that it was supposed to be a satire, but my aversion to the subject matter and lingering doubts about the facile cynicism of Denys Arcand’s previous feature, The Decline of the American Empire (1985), made me fear the worst.

I was wrong. While the new film isn’t entirely unpretentious, it actually makes me nostalgic for the kind of pretension that non-English-language art films used to be able to get away with — the kind of pretension (or maybe just thoughtfulness) that three decades of Yankee jeers have driven from our screens. (I know it’s our patriotic duty to “have fun” at movies, but why does fun habitually have to be equated with absence of thought?)

I think what I like most about Jesus of Montreal is its spirit of inquiry, which is much stronger than its rhetoric. That is, it doesn’t (quite) say, “This is what would happen if Jesus came back today,” and it doesn’t even (quite) ask, “What would happen if Jesus came back today?” What it asks us to consider is how we might think about Jesus in terms of today, and how we might think of today in terms of Jesus — and while Arcand’s plot broaches these issues, it’s not confined to them.

An actor in a costume drama named Daniel Coloumbe (Lothaire Bluteau) is spotted by a Catholic priest (Gilles Pelletier), who invites him to “modernize,” restage, and play the lead role in a passion play that is held annually for tourists on the grounds of a church overlooking downtown Montreal. Daniel enlists Constance (Johanne-Marie Tremblay), a friend from acting school now working in a soup kitchen, to play Mary Magdalene; Mireille (Catherine Wilkening), a French model working in TV commercials, is signed up to play the Virgin Mary; and two actors — one who dubs porn films for a living (Remy Gerard) and another who lectures at a planetarium (Robert Lepage) — fill the other parts. Living collectively in Constance’s apartment, they write the new version of the play.

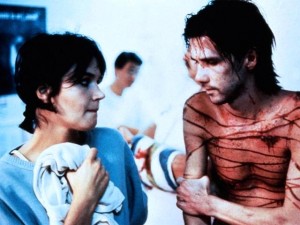

Although the premiere of their avant-garde production — which moves with the audience to different locations, one for each of the 14 stations of the cross — is generally well received, the priest objects to many of their changes and wants them to revert to the earlier version of the play, which they refuse to do. Meanwhile, because they still have to make a living, Daniel accompanies Mireille to a TV-commercial audition; when the director, Mireille’s former boss and lover, humiliates her by ordering her to strip, Daniel becomes enraged, smashes all the video equipment, and chases everyone off the premises. This leads to a trial, where a slick lawyer offers to become Daniel’s agent, and the judge, played by director Arcand himself, sends Daniel to a psychiatrist. Later, in defiance of the priest, the actors give a final performance of their production and get into a fight with the police that ends with Daniel becoming critically injured . . .

Two underlying themes help Arcand avoid the overblown rhetoric that his subject seems to invite, and both contribute a great deal to the overall flavor. (Both of these themes, moreover, reinforce the Christian parallels fairly unobtrusively without making them seem forced or academic.) One concerns the dilemma of being French-Canadian (also important in Arcand’s previous feature) — the national identity crisis that stems from being in effect part of a doubly colonized country, a sort of territorial footnote to both France and the U.S. It imparts to Arcand’s satire a wry world-weariness and resignation to the idea that anything that happens in Montreal is ipso facto deemed less important than anything that happens in New York, Los Angeles, or Paris.

The other secondary theme is one found with the same intensity in certain Jacques Rivette films, one involving the intimate complicity and mutually nurturing camaraderie created among a small group of people doing idealistic, collective theater work. Arcand captures this feeling with a great deal of beauty and clarity, and the film’s major achievements would be unthinkable without it.

Although Jesus of Montreal isn’t above drawing certain parallels between the passion play and the contemporary plot — Daniel’s behavior at the audition clearly corresponds to Jesus’s response to the money changers, and the advertising executives and the slick lawyer evoke respectively the Pharisees and the devil — Arcand’s approach to his biblical source is casual rather than strictly allegorical. There’s also a fair amount of spirited satire of the various cultural milieus depicted, and other kinds of comedy that Arcand and his actors have a great deal of fun with: when a fellow actor doesn’t show up, the actor dubbing a porn film has to scramble between two microphones, playing two panting studs in the same scene; the priest turns out to be both an occasional lover of Constance and a frustrated actor who offers, in English, a fair imitation of Alec Guinness playing Richard III; we watch the shooting of a perfume ad that appropriates the title of Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being; and later we see the unnaturally prolonged phony smile of a TV commentator giving a vulgar plug to Pierre Trudeau’s memoirs.

The movie’s centerpiece, which is not especially satirical, is an abbreviated version of the passion play itself — a fascinating extended sequence that is in certain respects the best passage in the film. Alternately essayistic and dramatic, with most of the actors narrating as well as playing various parts, it contains everything from Christian miracles (such as Jesus walking on water and passing out loaves of bread to the spectators) to archaeological inquiry (Constance scraping dirt off a religious mosaic) to diverse historical speculations about Jesus. (One of these — the possibility that Jesus might have been the illegitimate son of a Roman soldier, based on references in Jewish texts of the period to Jesus as Yesha Ben Pantera rather than Yesha Ben Joseph — becomes the focus of the priest’s disapproval.)

Arcand, who received a Jesuit education, approaches this material with an open-minded curiosity that is neither strained nor irreverent. The very notion of a passion play being performed in contemporary Montreal is a subject rich with satirical possibilities, and the film takes advantage of some of these — particularly in the tour guide’s instructions to the audience between scenes (e.g., “This way to the second station — it’s a lot longer than last year” and “Last station — watch your step, it’s steep”) — but the production itself is treated with the utmost seriousness.

It’s hard to generalize about a film that is open-ended and freewheeling rather than programmatic about its overall structure, except to say that most of the conceits work. Unfortunately, two speeches — a planetarium lecture (which, if I’m not mistaken, is quoted verbatim from the planetarium lecture in Rebel Without a Cause) and the interjection by one actor, during the passion play, of Hamlet’s soliloquy — are somewhat muffled by approximate rather than precise English subtitles, but the limitations of subtitling, i.e., actually fitting all the words on the screen, are such that conveying the full original English texts was probably impossible. On the whole, the film is strongest when it isn’t pursuing its allegorical parallels too systematically or taking them too seriously — as it starts to do in the closing scenes, perhaps because the necessity of rounding out the plot made this unavoidable. On the other hand, as a portrait of Montreal today — and, more generally, the times that we’re living in — the observations of Jesus of Montreal are a good deal livelier, funnier, and more memorable than the relatively glum and glib pieties of The Decline of the American Empire.