From the Chicago Reader (May 13, 1988). — J.R.

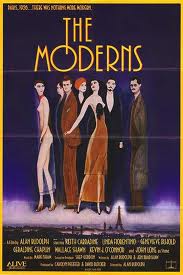

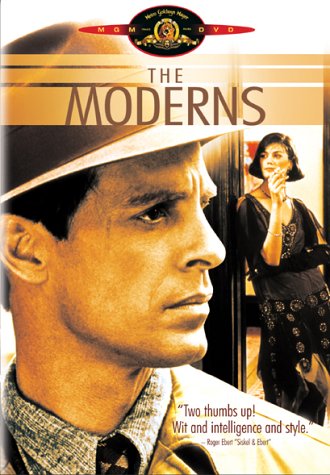

THE MODERNS

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Alan Rudolph

Written by Rudolph and Jon Bradshaw

With Keith Carradine, Linda Fiorentino, Geneviève Bujold, Geraldine Chaplin, Wallace Shawn, Kevin J. O’Connor, and John Lone.

For its first hour, at least, The Moderns gives us an Alan Rudolph very nearly back at the top of his form, on a level that approaches that of his two masterpieces, Remember My Name and Choose Me. The effort isn’t sustained — and the movie encounters a number of booby traps, emerging more than a little battle scarred — but it still qualifies as far and away the most ambitious Rudolph movie to date. Painters and art critics who were offended by the treatment of art forgery in Orson Welles’s F for Fake will probably be even more outraged by Rudolph’s tracing of related ironies, set in what purports to be the Paris of 1926. But those who are will be missing something enjoyable.

Fundamentally a gifted stylist with only a couple of effective stories to tell — usually “romantic” yarns that progressively unravel their own artificiality, inviting the viewer to reassemble them — Rudolph has had an unusually scattered and elusive career. If one puts together his more personal projects and his more expedient ones, it may come as a surprise to discover that The Moderns, which he has been trying to make since the mid-70s — coscripted by a journalist, Jon Bradshaw, who died before the film acquired financing — is his 12th movie to date.

His first two, and the only ones I haven’t seen — Premonition (1972) and Terror Circus (1973) — are so obscure that they’re routinely omitted from most Rudolph filmographies, and you won’t find them listed in recent editions of Leonard Maltin’s generally comprehensive TV Movies, either. His more official directorial debut, after work with Robert Altman as an assistant director and screenwriter, came with the pretentious but touching Welcome to L.A. (1976), followed by the wonderful and currently invisible Remember My Name (1978). (Altman produced both of these films and gets a special acknowledgment in the credits for The Moderns, so the connection remains an important one.)

Then, after three less personal and/or more compromised projects — Roadie (1980), Endangered Species (1982), and Return Engagement (1983), the latter a documentary about the curious touring duo of Timothy Leary and G. Gordon Liddy — Rudolph made his only hit and second masterpiece, the 1984 Choose Me. Next came Songwriter, someone else’s project, which he took over at the last moment, released the same year; Trouble in Mind (1985), as personal as Choose Me but more highfalutin and less successful; Made in Heaven (1987), another case of taking over someone else’s script, with mixed results; and finally The Moderns — which, for all its faults, is still my third favorite Rudolph to date.

Even at his best, Rudolph sharply divides audiences, who tend to become either intoxicated by or allergic to his dreamy style and the synthetic, do-it-yourself quality of his romantic/ironic plots and characters, which depend in part on the audience’s imagination for completion and coherence. Music nearly always plays a strong role in the blocking out of his mise en scène; one of my reasons for cherishing Remember My Name is the smashing Alberta Hunter/John Hammond recording session specially commissioned for the sound track. The music is in a way as central to the action as Geraldine Chaplin’s virtuoso performance, which forms a duet with it.

The Moderns differs most from all the preceding Rudolph movies in its foreign and period setting and in its theoretical and conceptual underpinnings, which make it by implication a rather abstract skeleton key to his other serious films. Modernism is certainly a major impulse behind his work, for all its Hollywood trimmings. Indeed, insofar as Rudolph regards Hollywood as the place that eventually took over the role of 1920s Paris — a point to which I’ll return — one might say that the “modernist” side of Hollywood and the “Hollywood” side of modernism are largely what The Moderns is all about, a rather fragile concept that only makes sense if the quotation marks are retained (as they usually are in Rudolph’s work).

The modernism of Rudolph is largely an extension of a preoccupation shared by Robert Altman (roughly from McCabe and Mrs. Miller through Nashville) and Jacques Rivette (more or less since L’amour fou), a preoccupation that both stems from and relates back to a total absorption in actors as actors. The notion that anything an actor does is interesting informs this preoccupation, meaning in practice that the character being represented is no longer confined to a single, fixed identity: masks and deception are the name of the game, and existential identity, what one does, is finally all that matters; what one is remains a mystery and puzzle whose solution has to be intuited from a sum of contradictory, self-canceling acts.

It hardly seems accidental that the lead characters in Remember My Name (Geraldine Chaplin) and Trouble in Mind (Kris Kristofferson) have just emerged from prison and the lead in Choose Me (Keith Carradine) just got out of a mental hospital; significantly, Bulle Ogier, the leading character in Rivette’s Le pont du nord, has also just emerged from prison. These characters are like blank checks waiting for the signatures of the spectators and the other characters they encounter. (The romantic couple in Made in Heaven, Tim Hutton and Kelly McGillis, are set up to suggest something similar.) They are sexy because they exude existential tensions; as pure distillations of possibility and potential, they are open invitations to the libidos and imaginations of whomever they encounter, on-screen or off.

To put across this theme, directors often invite the actors who play these blank-check roles to help invent their characters and write their lines. The result is often an exciting indeterminacy and sense of freedom about these characters that puts them well ahead of everyone else in their respective movies. In Remember My Name, Chaplin stalks through a southern California suburb with the grace, authority, and ferocity of Toshiro Mifune in Yojimbo; although she’s after revenge against the two-timing Anthony Perkins, it takes the whole movie to unravel this. Before it reaches this clarity, Chaplin’s performance has some of the modernist feel of a Richard Foreman or a Robert Wilson theater piece, signifying everything. In Choose Me, Keith Carradine’s character remains indeterminate up to the very end: he’s presented alternately as a psychopathic liar, mechanic, spy, gambler, photographer, pilot, poet, and essayist; he proposes marriage to virtually every woman he meets, and in the film’s magical closing moments, his bride, played by Lesley Ann Warren, views him alternately as a romantic dreamboat and a frightening lunatic.

Other characters in Rudolph’s paranoid, claustrophobic universe share this slippery quality of never being quite what they seem. Apparent poses and cover stories keep sliding away, a pop form of Proustian revelation, and the personalities that remain function as hypotheses rather than fully formed individuals. This is more or less the operating principle in the tightly closed world of The Moderns, where none of the characters — including, as it happens, Ernest Hemingway, Gertrude Stein, and Alice B. Toklas — is anything more than a sketchy suggestion, and nearly everyone seems to have something to hide. Spectators hoping for a literal rendering of the period and milieu are bound to be disappointed. The people on view are 80s types through and through, and at one point Rudolph pans across a smoky Paris bar to reveal a group of punks in order to underline this point. For better and for worse, it’s a Ragtime view of history, only more so; if we pick up on Rudolph’s clues, it’s easy to see that Paris 1926 is never more than a transparent cover for 1988 Hollywood.

A good many of the archetypal characters are assigned symbolic names. Hart (Keith Carradine), the hero, is an undiscovered and unsuccessful 33-year-old painter who reluctantly agrees to copy three canvases (by Cezanne, Modigliani, and Matisse) so that a wealthy art patron (Geraldine Chaplin) getting a divorce can contrive to keep the originals. In keeping with the modernist theme of self-referentiality, Hart’s activity is implicitly linked to that of Rudolph, who periodically switches from color to black-and-white in the film in order to match his re-created Paris of 1926 with newsreel footage. (To cinch the connection, Hart uses photography as a tool in making his forgeries; and to cinch the irony, the French pronunciation of his name yields “art.”) His dealer (Geneviève Bujold) is called Valentine — what is a valentine but a commercialized heart, a Hart placed on the market? A prophylactics tycoon (John Lone) who collects art, lives with Hart’s beloved Rachel (Linda Fiorentino), and even buys an example of Hart’s art — a painting of Rachel — for eventual use in an ad for rubbers is naturally called Stone. A cynical collector and investor, Stone frequently suggests an 80s movie producer, complete with cocaine and sweatpants.

The cafe bar frequented by all of the above, as well as by Ernest Hemingway (Kevin J. O’Connor), an influential journalist named Oiseau (Wallace Shawn), and a steady stream of American tourists, is run by a minor character named Rose Selavy, named after Marcel Duchamp’s imaginary female alter ego, who signed Duchamp’s only film, Anemic Cinema, made in 1926. (Her name is a pun for Duchamp’s “Eros, c’est la vie.“) It’s in the Bar Selavy, in fact, that Rudolph most frequently comes into his own as a director, gliding gracefully from table to table and from close-up to close-up like a stoned insect in nearly constant motion.

Rudolph’s use of shallow space and hazy lighting, so evocative of the interiors in McCabe and Mrs. Miller, makes virtually every location in The Moderns, inside or out, feel like the inside of a broom closet; Hart’s cramped Studio, cluttered with dozens of paintings, is like a miniature labyrinth, and the atmospheric spaces of the Bar Selavy, Valentine’s gallery, Stone’s mansion, Stein and Toklas’s Montparnasse flat, the American gym, and the narrow streets are all made to feel similarly congested and complexly interwoven. Despite the accentuated coziness, this world is anything but intimate and internalized; public appearances are all that matter. Consequently, the importance accorded to modernism in this film has nothing to do with its effect on individual psyches, and everything to do with its pop profile — its public calcification in advertising and media.

Clearly this is the spirit in which we’re meant to take the film’s parodic treatment of Hemingway as a young sot who spouts a steady stream of trial-balloon aphorisms, most of them flatfooted forays like “Marriage is absolutely bitched” or (to a semiconscious Hart who’s just been flattened by Stone) “A fight is just a fight — and when it’s fought, it’s something else.” But this is where the film’s problems start to become more acute. Even if we can accept this Hemingway as a purposeful parody — a fanciful and irreverent look at the man before his public profile froze into myth — it’s still no easy matter to accept the movie’s Stein and Toklas as anything other than crude and unconvincing pastiches, even of their slickest public selves. And the paintings by Hart that we glimpse, which are neither especially modernist nor especially good, may confuse us even further about what this movie is trying to say about “real” as opposed to ersatz and forged art — assuming that it suggests there’s a distinction worth making.

While it’s easy to be put off by these confusions, it would be a mistake to assume that Rudolph’s take on the period is purely satiric or purely cynical. To argue that the fate of “modernist” ideas in our present culture is to be used for advertising — and that the fate of “the moderns” was to become advertisements — is level-headed realism of a sort, not mere satire or cynicism. If we accept this point, moreover, it’s reasonable enough to argue further that the romantic function of these figures in the public imagination was subsequently taken over by Hollywood. This is where the “Hollywood” side of modernism, the “modernist” side of Hollywood, and the Rudolph habit of viewing reality and identity themselves in quotation marks come into play.

I doubt that any of us can buy it all; still, there’s a fair amount to be enjoyed, at least before the mechanism starts to run down. Carradine, Chaplin, and Bujold are always at their best in Rudolph movies, and all three shine here. People like myself who usually find Wallace Shawn’s performances grating and graceless may still have trouble with him here, although Rudolph seems to soften a few of his edges and has no problem integrating him into the ensemble playing. Stylistically, the movie bubbles with a series of rhymes and echo effects, many of which seem to play a modest and modernist self-referential role: Carradine and Chaplin pass a poster for a Dixieland band, which ushers in a patch of Dixieland music to accompany the scene; in two successive scenes of lovemaking with other people, Carradine and Fiorentino each say “Ow!” to signal their physical discomfort; and later on, Nathalie (Chaplin) calls Hart a brute twice, first with a French pronunciation, then in English. Even better, an overall sense of refrain and regret, like the reunion of the two leads in Johnny Guitar, underlines an extended scene between Fiorentino and Carradine in Hart’s studio, a scene that brims over with style and feeling. Whatever Rudolph does, whenever he’s doing it to music, a lot of it works.