From the October 15, 1980 issue of The Soho News. I should note the influence on my viewpoint of sexual politics in this article exerted by Sandy Flitterman, a feminist critic and one of the founding editors of Camera Obscura, with whom I was living in Hoboken during this period (roughly, 1979-1983). I should also note that my swipe at Coppola provoked an angry call from Tom Luddy, who was working for Coppola at the time. — J.R.

Every Man for Himself

Directed by Jean-Luc Godard

Written by Jean-Luc Godard,

Anne-Marie Miéville, and

Jean-Claude Carrière

Gloria

Written and directed by

John Cassavetes

Tih Minh

Directed by Louis Feuillade

In the latest lovely, desperate film by one of the most brilliant filmmakers alive, Jean-Luc Godard’s Every Man for Himself should be seen by everyone interested in movies or in life, without hesitation or delay. There are more ideas here per cubic second than one could find in a month of Paul Mazursky (or Ingmar Bergman) “think” pieces, and for this reason alone, Godard’s latest comeback is worth an hour and a half of anyone’s time.

Don’t let yourself get tripped up by the unfortunate masculine English title. The French that it strictly translates, Save qui peut (la vie), is genderless, save for the feminine article preceding the parenthetical “life”. (Ian Christie of the British Film Institute suggests Run for Your Life as a workable alternative.)

If I consider Sauve qui peut a relatively minor work in Godard’s canon -– infinitely preferable to the torturous Dziga Vertov Group films (roughly 1968-70), but less interesting, ambitious or groundbreaking than either Ici et ailleurs (1974) or Numéro deux (1975) -– I also readily acknowledge the necessity for Godard to make movies for Vincent Canby, Francis Coppola and Andrew Sarris as well as for myself and my friends. Indeed, the fact that Godard is no longer being quarantined and relegated to “the esoteric reaches of world structuralism” (an odd fantasy term employed in Sarris’ latest book, Politics and Cinema, that faintly conjures up the Red Menace of the 50s) should be regarded as cheering news for everyone.

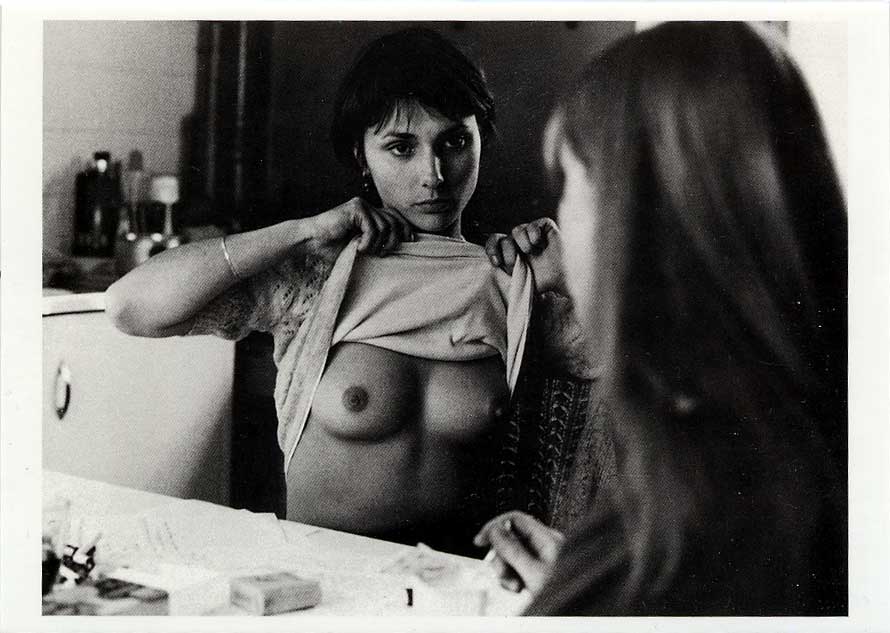

Godard’s commercial comeback involves stars, characters, plot, lush outer-space music, crisp 35mm photography, and humor, in addition to softcore sex (viewed from a quasifeminist perspective). A few years ago a woman avant-garde filmmaker [Yvonne Rainer] angrily insisted to me, in reference to Numéro deux, “Bare ass is bare ass -– I don’t give a god-damn how many video screens you put it on.” Then as now my counter-argument would run roughly as follows:

1. Unlike Sauve qui peut, Numéro deux de-eroticizes sex and nudity with a puritanical exactitude that rivals that of Jean-Jacques Rousseau or Jean-Marie Straub. And unlike some of my colleagues, I don’t consider this process to be an entirely negative one, even if it sells popcorn. (Would it really be so awful and dehumanized to have at least a couple of un-erotic ads for jeans on TV?)

2. Godard’s troubled sexuality -– a cumbersome central factor in most of his films –- was cogently described by Susan Sontag in a 1968 essay: “It has been noted that many of Godard’s films project a masochistic view of women, verging on misogyny, and an indefatigable romanticism about `the couple’. It’s an odd but rather familiar combination of attitudes.”

To this description, one should add the no less familiar voyeurism, evidenced in Save qui peut in the peekaboo shot of a prospective prostitute showing her breasts to Isabelle Huppert (a prostitute and her prospective pimp) -– an unexpected glimpse that Godard has to cut back to from a cutaway exterior shot in order to show. In relation to the particular talents of Godard’s latest employer, I think it wouldn’t be entirely inappropriate to dub this the Coppola Touch –- or, better yet, the Coppola Feel. (For comparable guilty pleasures, cf. The Conversation or the Playboy cuties in Apocalpypse Now.)

3. Arguably, the most that one should expect from Godard in any film is the translation of these problems into wider, nonautobiographical terms –- problems of life and politics, language and representation, exposition and spectacle. For better and for worse, these are all problems that can produce poetry, and because Godard –- like Eisenstein, Snow, and Kubrick –- is concerned with both the science of poetry and the poetry of science, use of his own problems as a starting point seems to me perfectly legitimate and, indeed, obligatory. (No wonder he is criticized as a poet and a scientist –- unlike lesser directors, who qualify as neither.)

As one feminist critic recently pointed out to me, who else but Godard has consistently succeeded in situating his sexuality within a social context? It sounds awfully European to say this, but all issues are viewed dialectically by Godard, giving him an analytical edge over most of the rest of us. Thus his social context always promotes an analytical understanding of how sounds and images and produced and read — including bogus and aberrated ones.

Example of a bogus sound: Huppert or her character faking an orgasm. Example of aberrated images: a farmgirl baring her ass to a row of cows (seen), the erotic fantasies of Jacques Dutronic’s character (“Mr. Godard”) about his preteen daughter (described). Examples of translation: Huppert’s impersonation of a client’s preteen daughter winds up being performed for an unseen female viewer (speculative). Another businessman client, ordering a complex, hilariously mechanistic orgy — aptly compared by Richard Corliss and others to a Rube Goldberg machine — says at one point, “That’s enough image, let’s work on the sound” (analytical).

***

The unexpected pleasure of John Cassavetes’ crowd-pleasing, charmingly acted, 100% hokum Gloria is the confidence it shows in flourishing old-fashioned Hollywood tropes. In contrast to the more scattershot methods in Cassavetes’ earlier work, the tight scaling down of incident and character — battered middle-aged moll (Gena Rowlands) with a precocious 7-year-old Puerto Rican kid (John Adames), in flight from a malevolent mob in bombed-out sections of the Bronx, Manhattan, and Jersey — clicks along like a well-oiled suspense machine and, better yet, improbably delivers the shopworn goods. (Rowland fills the screen like Toshiro Mifune and stages violent confrontations with some of the aplomb of Geraldine Chaplin in Remember My Name.)

According to some local scribes, this all takes place in Never Never Land, unlike such alleged True-Life Adventures as An Unmarried Woman, Manhattan, and Kramer vs. Kramer. I’d argue, on the contrary, that it’s merely a fantasy serving different class, race, and temperamental interests, which include separate definitions of what’s real or important. Recalling Godard’s equations of cinema and voyeurism. I often wonder if “taste” in film criticism is any more than a rationalization of unacknowledged erotic preferences. From this standpoint, Gloria gets me off in a way that middle-class chic never could.

***

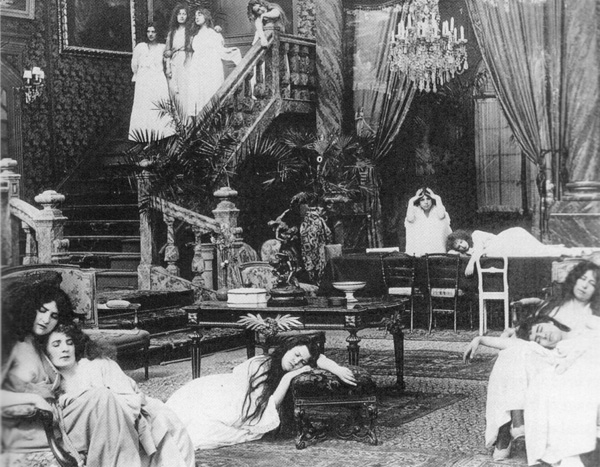

Eleven and a half years ago — when New Yorkers were still excited by and interested in movies (and imaginative new wave flics like Raul Ruiz’s Dogs’ Dialogue and Jackie Raynal’s New York Story, both plotty shorts recently shown at the New York Film Festival, would surely have attracted more understanding and sympathy) — I first saw Louis Feuillade’s magnificent 1918 crime serial Tih Minh at the Museum of Modern Art, , along with a sizable crowd of other delirious film freaks.

Set on the French Riviera, in opulent interiors approximating a Victorian chatchka heaven and spectacular sun-soaked exteriors (as resplendent with mystery as forests in fairy tales), this monumental documentary fantasy — the greatest, to my mind, in all of cinema — offered itself up like an impossible euphoric feast, a seven-hour stroll through the Garden of Eden.

It looked just as beautiful last week, expertly accompanied by pianist Curt Salke, at a sparsely attended Festival press show. It was over an hour shorter than the print I’d seen in 1969 (I especially miss a scene in which rich guests smoke hash on a parlor floor), but the extraordinary deep-focus photography and fluid editing were as stunning as ever. And the absence of all the intertitles [in the earlier print, from the Belgian Cinémathèque] may have made the images even more ravishing and primieval in their subservience to a somewhat out-of-reach narrative, thus even more abstractly suggestive. What has any of this sublime pleasure to do with the contemporary film scene? Nothing whatsoever.

—The Soho News, October 15, 1980