My column for the June 2015 issue of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

Although we often collapse the two into a single entity, it’s important to acknowledge that criticism and critical taste are far from identical or interchangeable. It’s instructive that Godard today considers Truffaut more important as a critic than as a filmmaker, and equally provocative to learn from both Dudley Andrew’s biography of André Bazin and the fascinating, lengthy interview with Resnais in Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues and Jean-Louis Leutrat’s 2006 book Alain Resnais: Liaisons secrètes, accords vagabonds (Cahiers du Cinéma) that Resnais originally functioned as Bazin’s mentor on film history during the German Occupation, especially on the subject of silent cinema, when he used to carry his 9.5 mm projector on his bicycle in order to show silent movies at La Maison des Lettres on rue des Ursulines, and Bazin, still fresh from the provinces, hadn’t yet encountered silent films in general or the early films of Fritz Lang in particular.

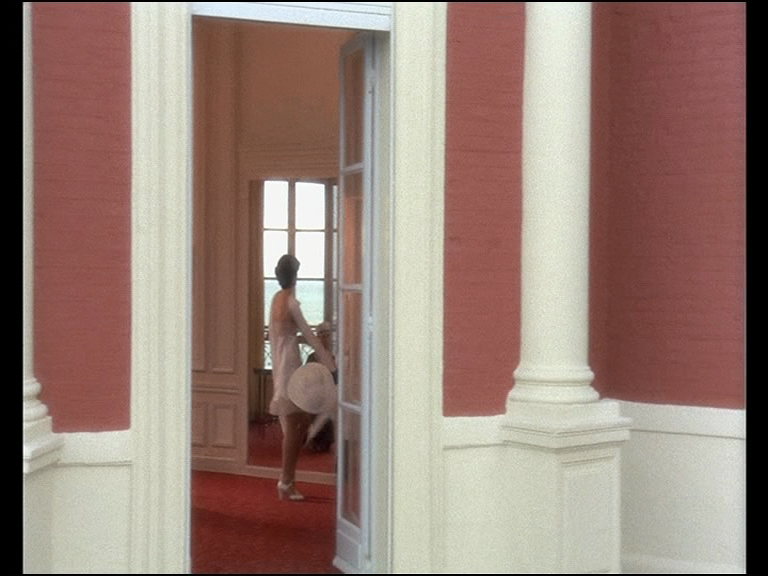

Unlike Bazin and Truffaut, Resnais was of course never a critic. Yet his critical taste was clearly every bit as central to his own films as Truffaut’s or Godard’s critical tastes and positions were to their own oeuvres. It might be argued, moreover, that Resnais’ artisanal craft when it came to studio shooting made him far more capable of emulating such directors as Hitchcock or Lubitsch than either Truffaut or Godard, who invariably had to resort to a kind of sketchy shorthand to display their appreciation of such filmmakers. (In Une femme est une femme, for example, the first mention of a character named “Lubitsch” [Jean-Paul Belmondo] is accompanied by Godard’s long shot of another character crossing an upstairs balcony to summon “Lubitsch” to the phone, where Resnais in Stavisky even went beyond Lubitsch himself to crane around an actual hotel rather than use a miniature for the same effect.) On the other hand, I believe that Truffaut’s early essay about Hitchcock’s use of doubling and “rhyming” shots in Shadow of a Doubt (“Un Trousseau de fausses clés,” Cahiers du Cinéma no. 39, octobre 1954), although he excluded it from all of his own books, strongly influenced not only the criticism of Godard. Chabrol, and Rohmer but also the filmic practice of Rivette in Céline et Julie vont en bateau roughly two decades later.

Nevertheless, it was Truffaut’s critical taste as reflected in his book-length interview with Alfred Hitchcock, far more than any of his critical essays, that radically altered global film culture when it came to taking Hitchcock seriously as an artist. This is acknowledged in the recent Criterion Blu-Ray and DVD release of Truffaut’s 1964 La peau douce (made during the same period), which includes two separate bonus features devoted to the relation of Truffaut to Hitchcock — a recent audiovisual, biographical essay written and narrated by Kent Jones, The Complexity of Influence, and a much longer and older documentary by Robert Fischer, Monsieur Truffaut Meets Mister Hitchcock (1999), that focuses more specifically on the book-length interview.

Jones is especially good in outlining the principal differences between Hitchcock and Truffaut as filmmakers, such as the focus on the “suspense of ordinary situations” that inflects the narrative of La peau douce, starting with the opening sequence, and including later scenes in an elevator and at a filling station, and more generally on Truffaut’s greater emphasis on character and literary forms of expression (such as letters). Fischer includes some excerpts from the actual conversations between Hitchcock and Truffaut, and includes an interview with Claude Chabrol that draws welcome attention to Truffaut’s direct imitation of a subjective-camera sequence from Hitchcock’s Notorious in which Ingrid Bergman’s character is greeted by Nazi spies with a sequence in La peau douce in which Jean DeSailly’s character is greeted by provincial critics, which Chabrol gently chides for being an overwrought application of Hitchcockian technique that exceeds dramatic utility. (In fact, Truffaut’s sequence also recalls and evokes the comic expressionism of Fellini’s 8 ½, which came out the previous year.) Both of these extras help to clarify the degree to which Truffaut’s emulation of his master tended towards rough approximations more than meaningful applications — unlike the exercise of his critical taste, which had far more lasting consequences.