Written for the Dutch magazine de Filmkrant, I believe in early 2004. –J.R.

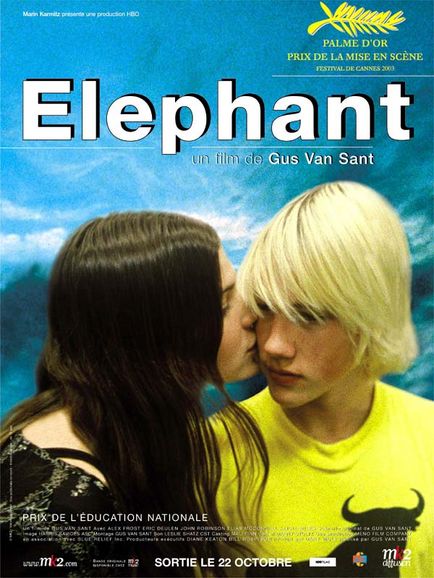

With Elephant, it’s a pleasure to welcome Gus Van Sant back to the land of the living. His film certainly has its flaws, yet its virtues so outshine them that his past few years in the wilderness can now be forgiven and mainly forgotten.

Gerry at least showed that, after the borderline sellout of Good Will Hunting and the all but unconditional sellout of Finding Forrester, Van Sant was still willing to take sizable risks. It was also interesting to hear him say he was inspired in those risks by such worthy role models as Chantal Akerman, James Benning, Andrei Tarkovsky, Bela Tarr, and Jacques Tati — even if the evidence of their influence wasn’t visible, apart from an overall interest in landscapes and duration.

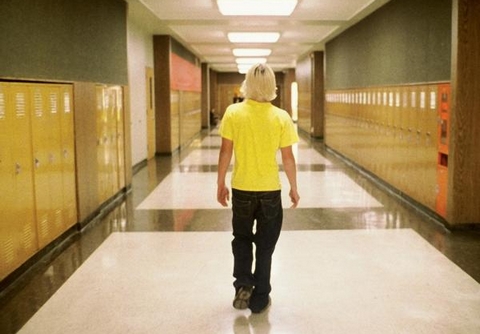

By contrast, at least two of the major influences on Elephant are plainly visible: Bela Tarr’s Satantango (primary) and Stanley Kubrick’s The Shining (secondary). From Satantango comes a complicated overlapping time structure that repeats the same events from a variety of viewpoints, each viewpoint being articulated in mainly extended takes that follow various characters as they walk through many adjacent settings. (Kubrick’s The Killing also repeats the same events from disparate viewpoints, but with offscreen narration and without all the walking and the intersecting trajectories.) And from The Shining comes the traversal of an endless procession of hallways, a sense of impending menace and bloodshed, a black male calmly and methodically coming to the rescue of those in danger until he’s abruptly thwarted, and a deep-freeze food locker used as a place of hiding and refuge.

Van Sant has so thoroughly assimilated these influences that he can’t be accused of simple imitation. Elephant is neither an interim report on the state of humanity like Satantango nor a horror story like The Shining, even though it can be said to carry traces of both. It was largely generated by talking to the high school students who were cast and shaping their parts on the basis of what they said about their own lives.

The two main lessons Elephant has to impart are both suggested by its title — which was inspired by another film, the late Alan Clarke’s 1989 BBC film of the same title about violence in northern Ireland. Van Sant reports that he originally thought Clarke’s title referred to the parable about several blind men examining an elephant and each one drawing a different conclusion based on which body part he was touching —- trunk, ear, tusk, tail, etc. He later discovered that Clarke was actually thinking about a saying whereby a problem is as easy to ignore as “an elephant in a bedroom”.

How do these two meanings come together? The problem of being a high school student may be as easy to ignore as an elephant in a bedroom, but it’s also as easy to misperceive as an elephant being examined by blind men, because each blind man perceives a separate animal. And in order to understand how these two propositions get played out in the film, it’s important to realize that Van Sant has no more of a concrete notion of why the Columbine massacres occurred than anyone else. All he has are a few wild guesses, and one could argue that most of the film’s flaws can be traced back to those guesses, which take up far more of our attention than they deserve.

What Van Sant is mainly interested in is how and why such a massacre wasn’t anticipated, and what this tells us about the climate in which it occurred. And here is precisely where the methodology of Satantango becomes crucial, because each time we follow a different character in order to brush past the same events from a different angle, we not only see things we didn’t see before; we’re also made to understand that our former narrative focus was blinding us in certain ways to everything that was going on. The subject of the film, in short, is what we miss and keep missing, regardless of how alert we are to the action we’re following. Each character is a separate story, and the event as a whole is gradually revealed as unfathomable because we can’t follow one story without partially overlooking another one as we graze past it.

Since most of the film’s events are realistic and believable, the few that aren’t register as lapses. Overall, Van Sant is less sensitive towards the girls than he is towards the boys, and in the case of Brittany, Jordan, and Nicole, his treatment is crudely parodic. It’s bad enough that all three girls are shown entering successful toilet stalls to chuck up the lunch they’ve just eaten; the fact that they’re previously allotted less than two minutes to consume that lunch, during the last part of what is probably the most elaborately and impressively choreographed shot in the film —- makes the conceit even more ludicrous.

The stories of Elephant are all incomplete by design, and not only because death in some cases nips them in the bud, but also because we’re following the lives of characters over the span of a few hours at the most, and in some cases over less time than that. Furthermore, we’re catching the trajectories of all of them piecemeal, in successive installments, while shifting periodically to other characters, sometimes leaping past gaps in the continuity that are never recovered. And most of the incidents we’re watching are relatively banal, though some of them gain in resonance retroactively.

Throughout the film, the nearly constant changes of light beautifully captured in Harris Savides’ cinematography and the other fleeting details that pass our line of vision create a sense of continual flux. Yet the tendency to stay with a single character —- apart from a few occasions when we pan from one to character to another —- fosters the impression that a particular strand is being woven into a single narrative tapestry, which implies that we’ll eventually wind up with a lucid overall picture. The problem with this assumption is that we can never see enough to take in the whole action, and one reason why we can’t is that adding up all the viewpoints doesn’t necessarily yield a global picture. Too much of the action never appears on-screen, and we’re hampered even further by the constraints of usually staying with one character at a time. As in Satantango, this method tends to implicate us morally with whoever we’re following or accompanying, regardless of whether we like the characters or not, because we stay with them for so long.

The immediate source of Elephant’s narrative structure may be Tarr’s film, but that in turn is based on a Hungarian novel by Laszlo Krasznahorkai employing the same structure, and I would guess that Krasznahorkai’s structure, which resembles that of William Faulkner in Light in August, can ultimately be traced back to Joseph Conrad in novels such as Nostromo (Faulkner’s likeliest source). In our imaginations and recollections, this structure constructs a three-dimensional world in successive layers, like a cubist painting, but since our moment-to-moment experience of the work is both confined and linear, we’re constantly being brought up short by being alerted to details that we missed in the previous layer. It all comes down to Van Sant’s way of telling and not telling his story —- which explains how a problem as blatant as an elephant in a bedroom can’t even be recognized if we’re so blind that we can only size up the animal one piece at a time.