From the Chicago Reader (February 1, 1991). — J.R.

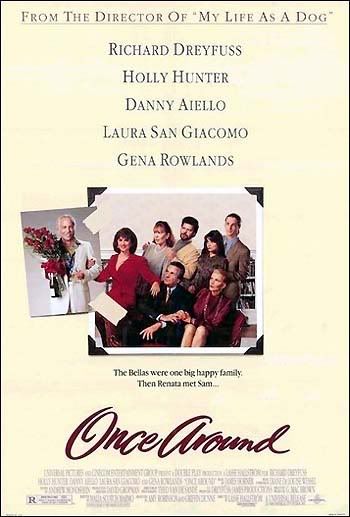

ONCE AROUND

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Lasse Hallstrom

Written by Malia Scotch Marmo

With Holly Hunter, Richard Dreyfuss, Danny Aiello, Gena Rowlands, Laura San Giacomo, Roxanne Hart, Danton Stone, and Tim Guinee.

“I don’t know much about art, but I know what I like.” This standard expression of cheerfully blinkered American consumption tells us a lot about the way we think, especially if we substitute other words and phrases for “art” — terms such as life, the world, democracy, the Middle East, Kuwait, or Iraq. By concentrating on what we like, our media excel in holding and gratifying our attention — without broaching the broader issue of our ignorance, which might, after all, upset and confound the steady (if highly selective) information flow. Whether the movie in question is CNN’s recent made-for-TV miniseries Crisis in the Gulf and its popular sequel War in the Gulf (both assigned catchy, lurid logos with flaming red letters) or an effective theatrical release like Once Around, its power to grip us and persuade us is largely predicated on a series of absences and elisions designed to forestall and even silence our curiosity about what we don’t know, along with well-prepared servings of what we know we like.

It may seem indecent to compare news reports about a real war in which real people are being killed with a fictional entertainment. It might also seem unfair to Malia Scotch Marmo, the screenwriter of Once Around, who started work on this domestic Hollywood comedy-drama and love story many years ago, long before the gulf war was even a gleam in George Bush’s eye. But it isn’t my intention to belittle the war or overinflate the importance of a better-than-average movie. I’m interested, rather, in exploring a couple of issues: the degree to which the meaning of any movie is determined by the precise period in which we see it, and the extent to which a movie, even a good movie, may have something to say about us and our strategies of avoidance that is not necessarily congruent with its conscious intentions.

The talents that have shaped our perception of the major characters in Once Around bear some relationship to the talents that have structured our perception of the war and what it entails. This is true despite the fact that a movie such as Once Around exists largely to help us forget certain troubling realities for a couple of hours, the war included.

I’ve come mainly to praise Once Around, not to bury it. Yet what I like about the film is so inextricably tied up with what troubles me about it that I can proceed only by balancing each argument on its behalf with an argument against it.

For: Four of the five major characters in Once Around belong to a well-to-do Italian American family based in Boston: Joe Bella (Danny Aiello), a sentimental patriarch; his wife Marilyn (Gena Rowlands); and their two daughters, Renata (Holly Hunter) and Jan (Laura San Giacomo). (The family also includes a son and a daughter-in-law, played by Danton Stone and Roxanne Hart, but they’re less central to the plot.) As the film opens, Joe is dreamily driving around a small, circular traffic island close to his house, singing to himself, shortly before the wedding of Jan to Peter Hedges (Tim Guinee, another relatively minor character).

Renata, the older daughter, is still unmarried and not happy about the fact, but when she presses her boyfriend (played by coproducer Griffin Dunne) for a proposal, he drops her. Deciding that she’s going to start selling condos, she travels to the Caribbean to attend a workshop, where she meets an aggressive, vulgar, high-powered salesman named Sam Sharpe (Richard Dreyfuss) — the fifth major character in the movie. They are immediately attracted to one another; they return to New York where he works, and then he takes her home to Boston in his stretch limo. He soon becomes an integral part of the Bella household, to the irritation of everyone in the family except Renata and Marilyn (who seems to be reserving judgment). But Sam agrees to shift his business to Boston, and Renata goes on being infatuated with him — and so the family is won over, and the two are eventually married.

After Joe retires and Renata becomes pregnant, however, Sam’s assertiveness about his Lithuanian background and his overall brashness begin to grate more and more on Renata’s family, leading to increasingly bitter conflicts . . .

I’ve only recently caught up with My Life as a Dog, Swedish director Lasse Hallstrom’s sixth feature (Once Around, his first American picture, is his ninth), the only one of his Swedish movies that’s had a general release in the U.S. It clearly has much in common with Once Around, in style as well as subject. Both movies are based on autobiographical fictions about growing up, whose heroes are painfully adjusting as they separate from their parents and make the transition from one family household to another. Both films abound in warm, sympathetic, and humorously eccentric characters. Both employ repeated visual motifs that serve as philosophical and emotional reference points for the larger implications of the narrative — including long shots of the houses that represent home for the leading characters and camera angles that imply “cosmic” overviews of the action. Both use popular songs almost obsessively in their plots (My Life as a Dog uses an old 78 recording of “I’ve Got a Lovely Bunch of Coconuts” in Swedish; Once Around uses “Fly Me to the Moon”). And both make memorable use of snowy landscapes and cheerful festive gatherings.

The major visual motif in My Life as a Dog is a recurring shot of the starry sky, accompanied by the offscreen reflections of the 12-year-old hero. The central visual motif in Once Around, which is developed much more elaborately, is an overhead shot of one or more cars circling the traffic island adjacent to the Bella house. At many points during the film Hallstrom links this image to others: a circular Lithuanian dance performed at Sam and Renata’s wedding, an impromptu dance performed by the Bellas and a belly dancer that traces a circle, circular camera movements around meals and other family gatherings, Joe’s ineffectual attempts to form a circular dish on a potter’s wheel. There’s also a striking scene after a family flare-up when Renata, very visibly pregnant and at home with Sam, is watching a home movie filmed during her childhood, and Sam, trying to get her attention, steps in front of the screen. After observing that she doesn’t want to look at him, he turns the projector around so that the movie is projected on her bare belly, enabling her to see the movie without seeing him. In the same scene the roundness of her belly is visually echoed by the spinning film reels and the illuminated projector lens. After the baby is born, Sam gets the other family members to form a “circle of love” with him around Renata and her daughter in the hospital; a close-up of the baby shows her with a teething ring.

Broadly speaking, these recurring circles all seem connected to the sexual self-confidence of either Joe or Sam. Sam specializes in telling crude jokes about penises, and immediately after he tells a couple at a workshop luncheon in the Caribbean, there’s a cut to an appreciative Renata removing a penis-shaped napkin from a napkin ring. The length of Sam’s stretch limo in relation to Joe’s convertible amplifies the sexual subtext when Sam takes Joe and Renata for a triumphant ride around the traffic island. This is further developed through Joe’s inability to shape a perfect circle on his potter’s wheel after his retirement. To clinch the sexual connection, Joe even makes a disparaging crack about the circular Lithuanian dance at the wedding being a “fertility rite,” with the dancers symbolically exposing their genitals.

Against: All of the above suggests an unusual amount of preplanned visual design for a mainstream Hollywood comedy. Yet one could argue that Once Around is weaker than My Life as a Dog in terms of the richness of the world it depicts and the number of issues it broaches directly rather than covertly.

The introduction of Ingemar, the young hero of My Life as a Dog, to sexual difference doesn’t need buried symbols or parenthetical wisecracks. It’s refreshingly explicit, and many of the film’s best sequences are devoted to spelling it out. When his older brother explains sex with the help of a bottle, Ingemar winds up getting his penis stuck inside one. A female playmate removes her underwear under a railroad trestle and embraces him just before trains pass overhead. After he’s sent off to live with his uncle, his best friend and boxing partner is a girl who dresses and acts like a boy, and he’s enlisted to help her disguise her growing breasts so she can continue to play on the soccer team. A bedridden lodger in his uncle’s house gets him to read aloud from ancient lingerie ads that the lodger carefully hides from the other members of the household. There’s also a striking sequence when he’s brought to a sculptor’s studio by his uncle’s buxom coworker, who’s been asked by the sculptor to pose in the nude and wants Ingemar to serve as chaperone. To get a better view of her body Ingemar climbs over the skylight on the roof and then crashes through it at the moment that he glimpses her head-on — a vivid illustration of the shock of sexual initiation that has no need of the sly subterfuge usually employed by Once Around to arrive at its sexual meanings. Indeed, none of the sexual details in My Life as a Dog smack of puritanical smuttiness, while nearly all of the sexual allusions in Once Around, whether overt or covert, are occasions for uptight smirks or snickers. (In the opening sequence, when Renata and Jan say “Fuck you” to each other, the audience is clearly signaled to laugh at the wittiness of the exchange.)

For all its slickness and visual ingenuity, Once Around is basically sitcom, unlike My Life as a Dog — wide-screen sitcom with four-letter words and off-color asides, but sitcom nevertheless. Many of the best character notations in the film (such as Joe’s ire at the sounds of Renata and Sam laughing late one night while they’re staying at his house, reflected in his announcement of how late it is quickly changing from 2 to 3 to 3:30) are worthy of Archie Bunker — and just as two-dimensional.

The first time I saw My Life as a Dog it was a dubbed version, and I found it unwatchable; it came across as an ersatz American story plastered over a Swedish one. The greater popularity of the dubbed video is a sad commentary on the taste of Americans, who seem to prefer foreign films when the characters are made to sound more like themselves — another indication of the lack of curiosity about the rest of the world that American movies, Once Around included, exploit. (Significantly, the movie’s side trip to the Caribbean doesn’t introduce us to a single native; as in much of the TV war coverage, Americans set against an exotic backdrop are the major bill of fare.)

For: Part of what’s wonderful about Once Around is the virtual perfection of the five lead actors. Another part is the unpredictable zigzag construction of Marmo’s script and her similarly unpredictable characters. Because the movie postulates character as plot and because the five leads match this conception with a steady stream of observations and surprises, we’re held throughout the film’s running time in a kind of delicious suspension.

From one point of view the story is about Renata –neurotically attached to her parents (after her boyfriend drops her, she asks to crawl into bed with them), longing to be swept off her feet, and ecstatic when she finally meets Sam. Hunter’s inventiveness with this character isn’t merely a matter of mastering a Bostonian accent (and thereby smothering her deep-south accent, which she has retained in other roles). It’s also a matter of countless grace notes of commentary on her character. When Renata initially makes flirtatious small talk with Sam, Sam says he’d like to buy her a dress in Tokyo; she reacts by saying “Wow!” and then becomes flushed with embarrassment at her burst of enthusiasm. Without overinflecting the moment, Hunter quickly sails through it as if it were actually happening to her.

From another point of view the story is about Sam, the odd man out in the tight family circle, and Dreyfuss hurls himself into the part in a way that’s calculated to confound our responses. Some viewers may find him so obnoxious that they wind up rejecting the film in toto, but his overbearing vitality motors so much of the action that we may be carried along by it in spite of ourselves.

From still another point of view the movie is about Joe — specifically the adjustments he has to make as his patriarchal power fades, a change brought on by his retirement and the usurping of his role by Sam. Aiello clearly knows this character like the back of his hand. (A supplementary pleasure is the grace and ease he shows as a singer in renditions of “Glory of Love” and “Fly Me to the Moon” and an a cappella version of the Italian tune “Mama.”)

Against: But one drawback to the zigzag construction of Marmo’s script and its use of red herrings is a compulsion to be offbeat even when it strains credibility or comes across as merely silly. The clearest example of this is a subplot in which Jan has an affair with a character named Jim (Greg Germann) just before her wedding; after she returns from her honeymoon, she’s cornered in the Bellas’ backyard by Jim, who drops to his knees and reveals that he’s engaged himself and wants Jan to come to his wedding. To add to the whimsy, his bride (Caroline Parton) is named Honey Beach. It’s never clear what this subplot is doing in the movie, unless it’s meant to characterize Jan as a flighty wife in relation to Renata. Yet apart from this subplot and Jan’s closeness to Renata, her character has little function in the film. (However, Laura San Giacomo too has mastered her Bostonian accent — in contrast to Aiello and Rowlands, who have no regional accent at all.)

In fact, practically all that we know about the film’s characters has to do with their intimate or familial interactions. When it comes to understanding how these people function in the world outside, this movie tells us zilch. (By contrast, My Life as a Dog lets us see Ingemar’s uncle at his glassworks job, and it also shows us as much about the local village life — and the more urban life Ingemar shares with his mother and brother — as it shows us of the hero’s life at his two homes.)

When Renata decides to sell condos for a living, we’re informed in passing that she was previously a waitress. There’s nothing else in the film that makes this easy to imagine — it seems like a stray fact plucked out of thin air. And it’s almost equally difficult to imagine her selling condos.

We don’t see Sam selling any condos either. His manner is that of a high-pressure salesman, yet the failure of the film to show him at work even momentarily — apart from a scene when he asks Joe to advise him about a couple of promotional brochures — raises the question of how someone so grandiosely self-absorbed can be as successful in business as we’re told he is. (On a couple of occasions we also see him ask an audience to give themselves a round of applause, but can this really adequately represent his professional behavior?) Similarly, while he rattles on at length about the Lithuanian generals he’s descended from, his entire family seems to have vanished as far as the plot is concerned. We never even find out whether he has any friends; the only emissaries from his “world” that we’re introduced to are a hired belly dancer, hired Lithuanian folk musicians, and a Lithuanian priest.

The only information that the movie imparts about Joe’s profession is one scene when he’s unloading boards from a truck in his driveway that’s labeled “Bella Construction Company.” The only other times we ever see him “at work” are at home, when he’s installing a lighting fixture or grappling with his potter’s wheel. Otherwise his professional identity remains a total blank. We also never find out what Tony and Peter do for a living, or whether Tony’s wife and Jan and Marilyn have any profession other than housewife. At one point we see the Bellas and many others at a memorial dinner in honor of Joe’s mother, but apart from this and the three weddings in the film, we see absolutely nothing of the roles played by any of the characters in relation to their communities.

Suppose we didn’t know that Joe ran a construction company or were incidentally told that he was a Mafia drug dealer or a poison-gas manufacturer or a crooked politician. The film’s pared-down universe implies throughout that his activity in the world outside his family — whether it’s ruthless or benign, honest or crooked, selfish or altruistic — makes no difference to who he is or what we should think of him. The same goes for everyone else in the movie except Sam, and the information that he’s a high-pressure salesman seems relevant only insofar as it affects his dealings with the Bella family and later on his health. In short, the “intimate” portraiture provided in the movie is predicated on a massive act of repression about who these people are, what they do, and what they mean in the world. Clearly none of this is supposed to matter.

I’ve suggested that the film can be read as being about Renata, Sam, or Joe. But the film might also be about another subject, a subject it frequently avoids — money. The plot as a whole hinges on the unstated but evident fact that all these characters have lots and lots of it. According to this scenario, the real conflict between Sam and the Bellas is the conflict between new money and older money. (From this vantage point — and certain others — the apparent focus on the difference between Italian and Lithuanian cultures merely conceals this movie’s real concern.) Sam resembles Joe in many respects — both men are aggressive patriarchs with sentimental attachments to their dead mothers and a passion for family rituals. But Sam registers as a vulgar parody of Joe because of his flagrant nouveau-riche style, which is largely what enrages Joe.

If the film’s theme of money is generally as covert as the theme of sex, both are significantly brought together on several occasions. When Sam takes Renata on an expensive clothes-shopping spree and afterward ogles her in the stretch limo while placing her hand over his crotch, we may be reminded of the similarly glitzy “money” scene in Pretty Woman when the hero buys the prostitute heroine sexy dresses — Richard Gere tells a clerk that he wants to spend “an obscene amount of money” and therefore requires “some major sucking up.” When Sam pays off the hired belly dancer, much is made of the fact that he sticks the bills between her breasts. Irritated by the opulence of Sam and Renata’s wedding, Joe complains that it seems as if he’s buying her. Later on, when Jan’s husband comes home and announces that he’s been given a bonus, he places the check behind his fly so she can fish it out. As in Pretty Woman, comedy that could have been inflected as social commentary is usually milked for shameless audience complicity. Indeed, throughout the film we’re invited mainly to revel in grandiloquent gestures rather than think about them — much as we’re invited to “participate” in CBS’s Showdown in the Gulf.

To tell the truth, I happen to like Once Around a lot more than I like the press coverage of the war in the Middle East — which, for most of us, alas, is the war in the Middle East — despite a lot of ambivalent feelings about both. But even if I liked the war and disliked Once Around, I doubt that the parallel forms of censorship that structure our experiences of both would be any less relevant. For better and for worse, we seem to be unusually gifted as a nation at telling stories and putting on shows. If our capacity for doing so entails a suppression of much of what makes these stories truthful and meaningful — or untruthful and meaningless — I guess that goes with the territory. (The fact that we know next to nothing about the people we’re killing in Iraq and Kuwait is more than incidental; it would be difficult to maintain the same sympathetic involvement in the war without this ignorance.)

If Once Around were more aboveboard about the sexual and economic tensions that underlie Joe’s hatred of Sam, we might conclude that when he rises to the occasion and magisterially throws Sam out of his house, his basic concern is with getting over his “wimp” complex. I saw some of the same surge of patriarchal energy in Bush’s shit-eating grin when he announced that we were going to war (and, incidentally, quoted with affection a soldier on the front named Hollywood). I don’t imagine that it would ever occur to Joe or to Bush that there are times when behaving like a “wimp” is more truly heroic than behaving like John Wayne, even if it’s less photogenic. But simple stories and spectacular shows are what we’re looking for, not edification about what lies beyond them. So simple stories and spectacular shows are what we get.