THE CROSS OF REDEMPTION: UNCOLLECTED WRITINGS by James Baldwin, edited and with an introduction by Randall Kenan, New York: Pant6heon Books, 2010, 307 pp.

I’ve only barely started to familiarize myself with this collection, but it’s already become apparent that this is far cry from what’s commonly known as “scraping the bottom of the barrel”. Indeed, as with James Agee’s collected non-fiction, one is discovering that the Library of America’s efforts at canonizing cantankerous eloquence is, let us say, a bit under-researched, to say the least (unless the problems are simply those of taste). Baldwin’s review for the Village Voice of Seymour Krim’s first collection of essays, the first thing I read here, is plainly superior to some of the things that went into the Library of America’s selection (and, as I’ve argued elsewhere, what I regard as the strongest essay Agee ever wrote, “America, Look at Your Shame!”, even if it was never published during Agee’s lifetime, is criminally omitted from both of LOA’s two Agee volumes).

I’ve encountered some other treasures in The Cross of Redemption, even at this preliminary stage, but let me zero in here on a single prophetic statement contained in the first paragraph of a 1961 Baldwin lecture that Kenan quotes from in his Introduction:

Bobby Kennedy recently made me the soul-stirring promise that one day — thirty years, if I’m lucky — I can be President too. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (March 24, 1989). — J.R.

LAWRENCE OF ARABIA

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by David Lean

Written by Robert Bolt

With Peter O’Toole, Alec Guinness, Anthony Quinn, Jack Hawkins, Jose Ferrer, Anthony Quayle, Claude Rains, Arthur Kennedy, and Omar Sharif.

Thanks to a meticulous restoration carried out by Robert A. Harris and Jim Painten, working with a team of specialists that ultimately included director David Lean himself, Lawrence of Arabia has been rereleased in all its original glory in a version that includes some footage that wasn’t even seen by most of the film’s earliest audiences (the original road-show version, released in late 1962, was cut by about 20 minutes before it went into general release). I won’t dwell upon the complex detective work carried out by the restorers, except to note that in order to make the version currently playing as complete as possible, the original actors even redubbed some of their lines, which were then electronically altered so that their present voices would sound like their voices 27 years ago. Lean was also permitted to make a few minor modifications in the editing, so that the definitive version of this epic about the enigmatic T.E. Lawrence and his unorthodox military career is actually a “final cut” that incorporates practically all of the material that was in the original version. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (August 23, 2002). — J.R.

George Axelrod’s 1966 black comedy about sexual hysteria and the American dream presents a view of southern California that rivals Nathanael West’s The Day of the Locust in its savagery and satirical insight. Tuesday Weld, in a career-defining performance, plays a luscious high schooler whose Mephistophelian classmate (Roddy McDowell) promises to get her everything she wants, and though the movie is sometimes too dark to be simply funny, a good bit of it is flat-out hilarious. Lola Albright is especially good as Weld’s mother, and the scene in which Weld and her father (Max Showalter) shop for sweaters may top Kubrick’s Lolita (as well as Nabokov’s) in its sheer audacity. Axelrod, directing his first feature, collaborated with Larry H. Johnson on the screenplay, adapting a novel by Al Hine; with Ruth Gordon, Martin West, and Harvey Korman. 102 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 2005). — J.R.

Assault on Precinct 13

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Jean-Francois Richet

Written by James DeMonaco

With Ethan Hawke, Laurence Fishburne, John Leguizamo, Gabriel Byrne, Maria Bello, Brian Dennehy, Drea de Matteo, and Ja Rule

John Carpenter’s first solo feature, Assault on Precinct 13 (1976), is an effective low-budget genre piece — a perfectly proportioned, highly suspenseful action story about a few individuals under siege. It’s derived in part from Howard Hawks’s 1959 western Rio Bravo: Carpenter directly quotes from the dialogue and action, and he jokily adopts the pseudonym of John T. Chance, the name of John Wayne’s character, as the credited editor. The film is also influenced by claustrophobic horror movies such as The Thing (which Carpenter subsequently remade), The Birds, and Night of the Living Dead, especially their depiction of how unstable group dynamics are affected by an impersonal menace.

After most of the employees of a police station in a Los Angeles ghetto have moved to a new building, the station is attacked by a vengeful gang that uncannily expands into a mob, to the accompaniment of Carpenter’s relentlessly minimalist, percussive synthesizer score. A black rookie named Bishop and two white secretaries are the only remaining staff, and once Bishop realizes they can’t survive without help, he frees two prisoners, one black, one white — both hardened criminals en route to the state pen. Read more

My column for the June 2015 issue of Caimán Cuadernos de Cine. — J.R.

Although we often collapse the two into a single entity, it’s important to acknowledge that criticism and critical taste are far from identical or interchangeable. It’s instructive that Godard today considers Truffaut more important as a critic than as a filmmaker, and equally provocative to learn from both Dudley Andrew’s biography of André Bazin and the fascinating, lengthy interview with Resnais in Suzanne Liandrat-Guigues and Jean-Louis Leutrat’s 2006 book Alain Resnais: Liaisons secrètes, accords vagabonds (Cahiers du Cinéma) that Resnais originally functioned as Bazin’s mentor on film history during the German Occupation, especially on the subject of silent cinema, when he used to carry his 9.5 mm projector on his bicycle in order to show silent movies at La Maison des Lettres on rue des Ursulines, and Bazin, still fresh from the provinces, hadn’t yet encountered silent films in general or the early films of Fritz Lang in particular.

Unlike Bazin and Truffaut, Resnais was of course never a critic. Yet his critical taste was clearly every bit as central to his own films as Truffaut’s or Godard’s critical tastes and positions were to their own oeuvres. Read more

These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the first dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

Actress

Stanley Kwan’s 1991 masterpiece (also known as Ruan Ling-yu and Center Stage) is still possibly the greatest Hong Kong film I’ve seen; perhaps only some of the masterpieces of Wong Kar-wai, such as Days of Being Wild and In the Mood for Love (both of these also significantly period films) are comparable in depth and intensity. The story of silent film actress Ruan Ling-yu (1910-’35), known as the Garbo of Chinese cinema, it combines documentary with period re-creation, biopic glamour with profound curiosity, and ravishing historical clips with color simulations of the same sequences being shot — all to explore a past that seems more complex, sexy, and mysterious than the present. Maggie Cheung won a well-deserved best actress prize at Berlin for her classy performance in the title role, despite the fact that her difference from Ryan Ling-yu as an actress is probably more important than any similarities. In fact, she was basically known as a comic actress in relatively lightweight Hong Kong entertainments prior to this film, and Actress proved to be a turning point in her career towards more dramatic and often meatier parts. Read more

This was written in May 2014 for an Italian volume about fantastique cinema between 1980 and 2010 coedited by Antonio Gragnaniello. — J.R.

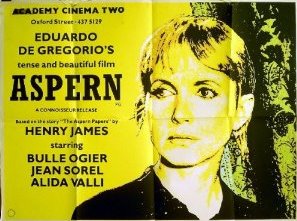

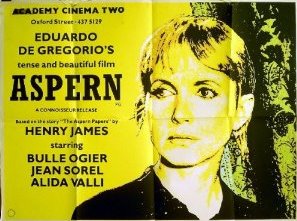

Speaking to Tom Milne and Richard Combs in Monthly Film Bulletin, the director of Aspern, Eduardo de Gregorio (1942-2012), avowed that “it was never meant to be a fantastique film”— which isn’t surprising given that its source, Henry James’ novella The Aspern Papers, has no relation to that genre either. But it was regarded by several French critics as having some relation to fantastique, apparently for two reasons: because fantastique as opposed to fantasy is often regarded as a matter of style and/or atmosphere rather than content, and because the better known works of de Gregorio — such as his scripts for Jacques Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau, Duelle, and Noroît and his own Sérail and Tangos volés—clearly belong to fantastique, while his work as a whole has clear links to both the 19th century Gothic tradition and the so-called “magical realism” of 20th century Latin American literature.

Even though much of Henry James’ dialogue is carried over into Aspern (translated into French), its basic plot — an obsessive literary scholar (the narrator in James’ tale) insinuates himself into the Venice household of an aged woman cared for by her lonely spinster niece with the aim of procuring her love letters from Aspern, a long-deceased romantic poet she was once involved with — undergoes several decisive changes in de Gregorio’s version, scripted by his partner at the time, Michael Graham. Read more

From The Soho News (November 24, 1981). — J.R.

Nick’s Movies (Nicholas Ray retrospective)

The Public Theater through December 13

Fantasy and counter-fantasy are perpetually at war in the films of Nicholas Ray — accounting in no small measure for the highly charged heat, light, fury, beauty, and pain that most of them project. In its most brilliant representations — the separate divisions of Vienna’s saloon in Johnny Guitar (1954), an almost surrealist Western; the house and mind of Ed Avery in Bigger Than Life (1956), an almost expressionist domestic melodrama — this graphic warfare actually becomes expressed in terms of discrete zones of action and confinement. “Down there I sell whisky and cards,” announces the imperious Vienna (Joan Crawford) on a stairway, gun in hand, to an itchy search party below that’s somewhere between a lynch mob and a sheriff’s posse. “All you can get up these stairs is a bullet in the head.”

Or consider another scene, one of the most memorable jaded love duets in movies, again spelled out through architecture and spatial balances as well as words and faces. Johnny Guitar (Sterling Hayden) sits at a kitchen table, drink in hand, while Vienna stands behind him, on the other side of a serving window, also facing us. Read more

Children of Men ***

Directed by Alfonso Cuaron

Written by Cuaron, Timothy J. Sexton, David Arata, Mark Fergus, and Hawk Ostby with Clive Owen, Julianne Moore, Claire-Hope Ashitey, Michael Caine, Pam Ferris, and Chiwetel Ejiofor

Pan’s Labyrinth ****

Directed and written by Guillermo del Toro

With Sergi Lopez, Maribel Verdu, Ivana Baquero, Ariadna Gil, and Doug Jones

Over the past few years three highly talented and ambitious young Mexican film directors — Alfonso Cuaron, Guillermo del Toro, and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu — have made their way into the American mainstream. All three seem to have managed this trick by defining themselves mainly in terms of genre, which isn’t surprising given the industry’s insistence that everything be defined according to pitches and formulas, all in 25 words or less — the consequence of a desire to exhaust existing markets rather than attempt to nurture or create new ones.

Cuaron’s done some children’s fantasy (A Little Princess, Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban) and literary adaptation (Great Expectations), a sex comedy/road movie/coming-of-age story (Y Tu Mama Tambien), and now an action-adventure/SF/war movie (Children of Men). His most ambitious movies seem to cram together several genres — or at least the suits’ notions of genres. Read more

Here are three of the 40-odd short pieces I wrote for Chris Fujiwara’s excellent, 800-page volume Defining Moments in Movies (London: Cassell, 2007), each of which describes an extraordinary scene from an Alain Resnais film involving camera movement. (There’s also a pretty amazing crane shot in Wild Grass, by the way.) — J.R.

***

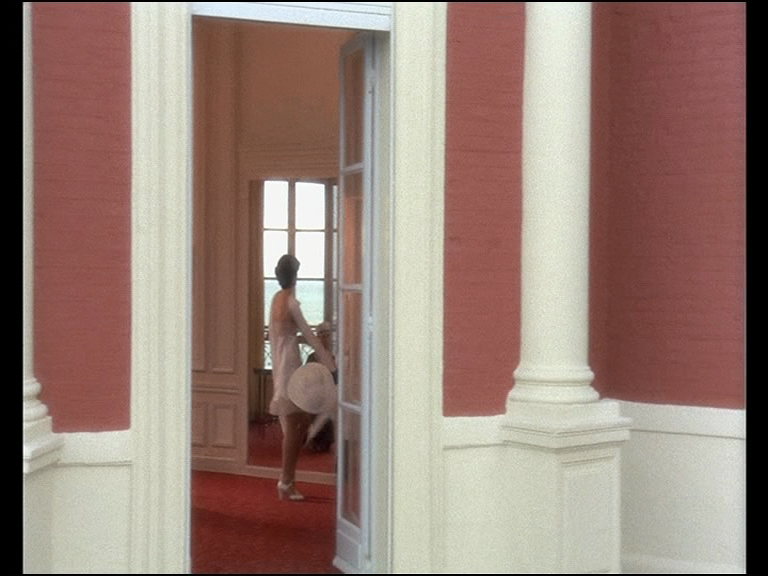

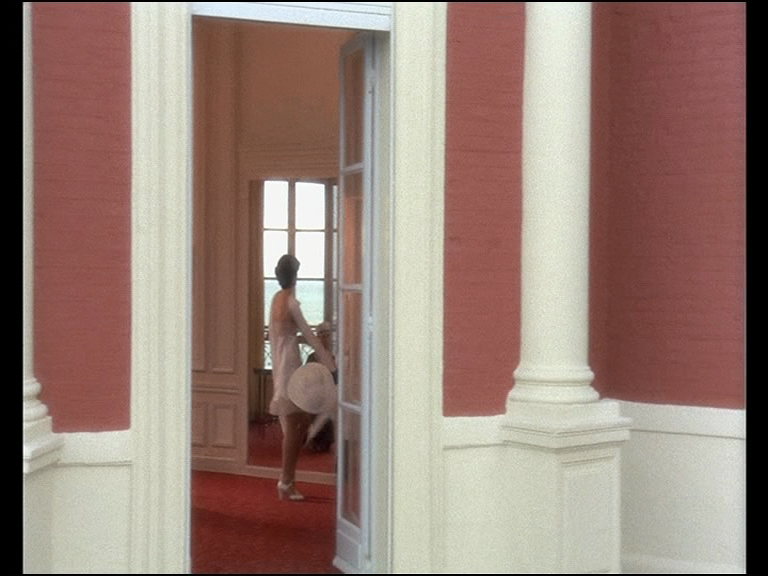

1961 / Last Year at Marienbad – The camera rushes repeatedly through the doors of Delphine Seyrig’s bedroom and into her arms.

France/Italy. Director: Alain Resnais. Cast: Delphine Seyrig, Giorgio Albertazzi. Original title:L’année dernière à Marienbad.

Why It’s Key: A climax of erotic reverie in a film of erotic reveries.

Alain Resnais’ most radical departure from Alain Robbe-Grillet’s published screenplay for Last Year at Marienbad is his elimination of what Robbe-Grillet calls a “rather swift and brutal rape scene”. In this ravishing puzzle film about an unnamed man (Giorgio Albertazzi) in a swank, old-style hotel trying to persuade another guest (Delphine Seyrig), also unnamed, that they met and had sex there the previous year, illustrated throughout by subjective imaginings that might be either his or hers, Resnais includes only the beginning of such a scene when the man enters the woman’s bedroom and she moves back in fear. Read more

This was written in 1982 for The Movie: An Illustrated History of the Movies in the U.K., about a movie released the same year. — J.R.

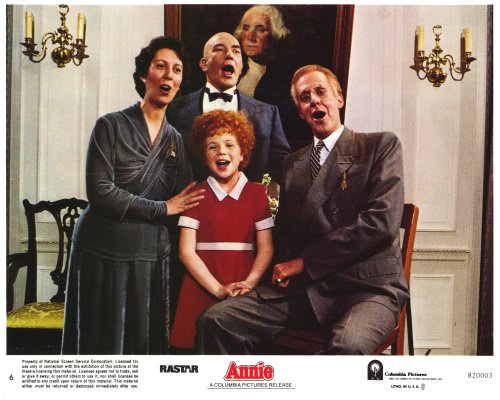

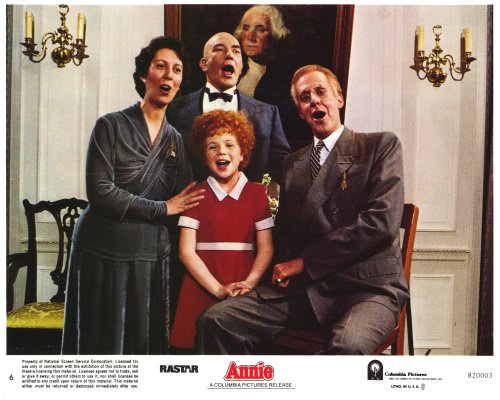

“Little Orphan Annie,” a right-wing comic strip drawn by Harold Grey, was premiered in the New York Daily News in 1924, eventually reaching millions of people through syndication in over five hundred newspapers. In a 1937 survey this feature with its little red-headed heroine was declared the most popukar comic strip in America.

Given the parallels between the economic climate of the Eighties and the period represented in the strip, there is a temptation to translate the main political message of the film Annie as meaning, “Let ’em eat cake” — the essential thrust, after all, of many a Thirties Depression musical, when opulent splendor was largely what the impecunious audience was paying to see (in the Broadway show, this aspect of Annie was reportedly even broader).

An attempt to liberalize the original strip to fit in with the Eighties seems to be behind a central sequence in the film in which Daddy Warbucks (Albert Finney) takes Annie (Aileen Quinn) and his personal secretary Grace (Ann Reinking) to Washington DC to meet Franklin D. Roosevelt (Edward Herman) and his wife Eleanor (Lois de Banzie); they try (with the help of Annie singing “Tomorrow”) to persuade Warbucks to run one of the “New Deal” youth employment programs. Read more

From the December 4, 2004 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Million Dollar Baby

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Clint Eastwood

Written by Paul Haggis

With Eastwood, Morgan Freeman, Hilary Swank, Jay Baruchel, and Mike Colter

The Aviator

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Martin Scorsese

Written by John Logan

With Leonardo DiCaprio, Cate Blanchett, Alec Baldwin, Alan Alda, John C. Reilly, Kate Beckinsale, Adam Scott, and Ian Holm

Despite his grace and precision as a director, Clint Eastwood, like Martin Scorsese, is at the mercy of his scripts. But in Million Dollar Baby he’s got a terrific one, adapted by Paul Haggis from Rope Burns: Stories From the Corner.

This book was the first published work by Jerry Boyd, writing under the pseudonym F.X. Toole, after 40 years of rejection slips. Boyd had been a fight manager and “cut man,” the guy who stops boxers from bleeding so they can stay in the ring, and he was 70 when the book came out; he died two years later, just before completing his first novel. This movie is permeated by those 40 years of rejection, and the wisdom of age is evident in it as well. Henry Bumstead, the brilliant production designer who helped create the minimalist canvas — he was art director on Hitchcock’s Vertigo (1958) and has been working for Eastwood since 1992 — will turn 90 in March, and Eastwood himself will be 75 a couple months later. Read more

This was published as my ninth one-page column in Cahiers du Cinéma España; it ran in their January 2009 issue (No. 19). — J.R.

It’s by no means unusual for a “retired” film scholar such as myself to find more work as a freelancer since my retirement late last February than I did for most of the previous two decades as a staff reviewer for the Chicago Reader. Two of my contemporaries, both former academics and both friends of mine — the slightly younger David Bordwell and the slightly older James Naremore — have told me that they’re busier nowadays than they were when they were teaching. But what seems more surprising, at least to me, is how much of my time recently has been consumed by my participation in panels and symposia, both in print and in person, about the alleged death of film criticism. The October issue of Sight and Sound is full of ruminations on this subject, under such headings as “Who needs critics?” and “critics on critics”; so is the Autumn issue of Cineaste, where the stated topic is “Film Criticism in the Age of the Internet: A Critical Symposium”. A week from now, I will be flying from Chicago to the New York Film Festival to speak on a panel called “Film Criticism in Crisis?” Read more

Written for the New York Times‘ online “Room for Debate: The Polanski Uproar” on September 29, 2009, in response to the following question:

“The recent arrest of Roman Polanski, the film director who fled to France from the United States in 1978 on the eve of sentencing for having unlawful sex with a 13-year-old girl, has caused an international ruckus. The French culture minister, Frédéric Mitterrand, and the French foreign minister, Bernard Kouchner, both issued statements of support for Mr. Polanski. But many others in France have expressed outrage at that support and said he should face justice for the crime.

“While it’s clear that the film industry forgave Mr. Polanski long ago, should society separate the work of artists from the artists themselves, despite evidence of reprehensible or even criminal behavior?”

Jonathan Rosenbaum:

I’m not at all in favor of giving artists free passes when it comes to their personal morality. But in the case of Roman Polanski, anyone who’s bothered to follow the history of his case in any detail is likely to conclude that (a) he’s already paid a great deal for his crime, (b) the interests of journalism and the entertainment industry in this matter usually have a lot more to do with puritanical hysteria and exploitation than any impartial pursuit of justice. Read more

Three brief entries commissioned by Chris Fujiwara and submitted in March 2009 for the updated Italian edition of his stupendous 2007 collection Defining Moments in Movies, entitled Cinema: 1000 Momenti Fondamentali. — J.R.

Key Event

Rossellini goes to India

Roberto Rossellini’s extended trip to India comes at the end of his richest period as a filmmaker in which his various staged encounters between fiction and non-fiction were most adventurous. At the war’s end he was primarily concerned with the human devastation in Italy and Germany, but once he began working with Ingrid Bergman, with whom he was living after their affair busted up both their marriages, domestic issues came to the fore, particularly in such features as Europa 51, Voyage to Italy, and Fear. Other bold forays during this period include a feature about Saint Francis of Assisi, a comic fantasy called The Machine That Killed Bad People (about a still camera that turns its subjects into statues), and a direct-sound recording of a play starring Bergman, made at a time when all films in Italy were dubbed.

When he traveled to India at age 51, Rossellini worked concurrently on his masterpiece India Matri Buhmi (1959), a set of interlocking tales and commentaries which Jean-Luc Godard once called “the creation of the world,” and a ten-part television miniseries that was broadcast in both France and Italy the same year. Read more