Missing from this review from the July 1975 Monthly Film Bulletin is any acknowledgment that Godard and Gorin’s rather punitive analysis against Jane Fonda’s role in a still photograph might have incidentally reflected some misogyny along with their resentment against the power of a movie star. For those interested in tracking down Letter to Jane, it’s included as an extra on the Criterion DVD of Tout va bien. —J.R.

Letter to Jane

France, 1972 Directors: Jean-Luc Godard, Jean-Pierre Gorin

Letter to Jane was initially made to be shown in a specific limited context: as a short accompanying Tout va bien at the New York and San Francisco Film Festivals in 1972. As with all of Godard and Gorin’s joint projects, the essential aims of the film are demystification and political analysis. More generally, it pursues a demystification of cinema itself as art object, reflected in the minimal technical means used in the articulation of the filmmakers’ argument (a montage of stills separated by cuts or makeshift wipes accompanied by the voices of Godard and Gorin in English, with brief uses of recorded music as punctuation) — an approach further developed by Godard’s more recent work with video, which seeks to demonstrate that the “production of sounds and images” need not be as expensive or as technically elaborate as is usually supposed. Read more

These are expanded Chicago Reader capsules written for a 2003 collection edited by Steven Jay Schneider. I contributed 72 of these in all; here are the third dozen, in alphabetical order. — J.R.

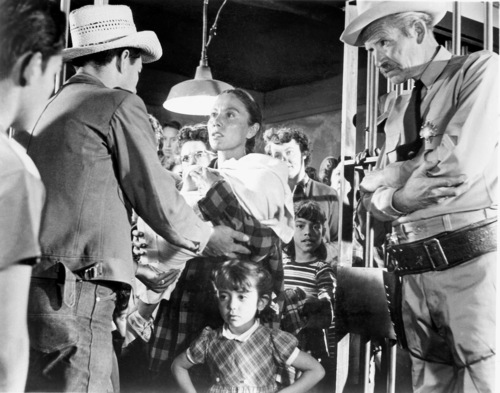

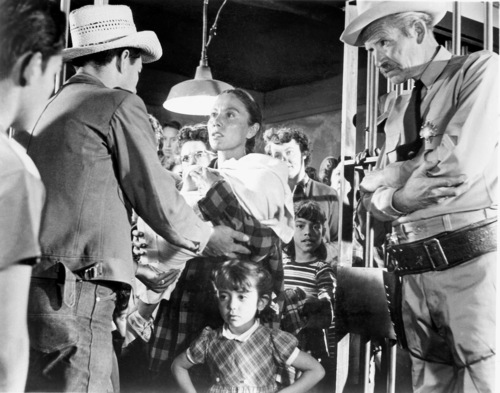

Salt of the Earth

This rarely screened 1954 classic is the only major American independent feature made by communists; a fictional story about the Mexican-American zinc miners in New Mexico then striking against their Anglo management, it was informed by feminist attitudes that are quite uncharacteristic of the period. The film was inspired by the blacklisting of director Herbert Biberman, screenwriter Michael Wilson (A Place in the Sun), producer and former screenwriter Paul Jarrico, and composer Sol Kaplan, among others; as Jarrico later reasoned, since they’d been drummed out of Hollywood for being subversives, they’d commit a “crime to fit the punishment” by making a subversive film. The results are leftist propaganda of a very high order, powerful and intelligent even when the film registers in spots as naive or dated. Basically kept out of American theaters until 1965, it was widely shown and honored in Europe, but it’s never received the recognition it deserves stateside. Regrettably, its best-known critical discussion in the U.S. is in Pauline Kael’s final essay in her first collection — a 1954 broadside in which this film is ridiculed as “propaganda” alongside a forgettable cold war thriller, Night People, that’s skewered as “advertising”. Read more

Born July 24, 1944, San Mareno, California. Died May 23, 2013, Chicago, Illinois.

Here’s something I said at a special tribute to Peter held in his presence at Columbia College, on October 4, 2012:

“For me, Peter Thompson is one of those special filmmakers who reinvents cinema for his own purposes, a trait that he shares not only with people like Robert Bresson, Carl Dreyer, and Jacques Tati, but also with filmmakers like Chaplin, Welles, and Kubrick.

“On some level, all of Peter’s films are mysteries and detective stories, but ones in which Peter is inviting us to join him in becoming the detectives, not in giving us puzzles that he knows how to solve but in inventing new ways for us to share in his curiosity. You might even say that part of the mysteries of his films is determining what they’re about, because in addition to reinventing cinema they might be said to reinvent things like subject matter and research as well as still more difficult-to-define entities such as poetry and history and truth.

“Peter has been a friend for about two decades, but I hasten to add that we became friends because of my enthusiasm for his early work, which existed before we ever met. Read more