From the Chicago Reader (February 15, 1991). — J.R.

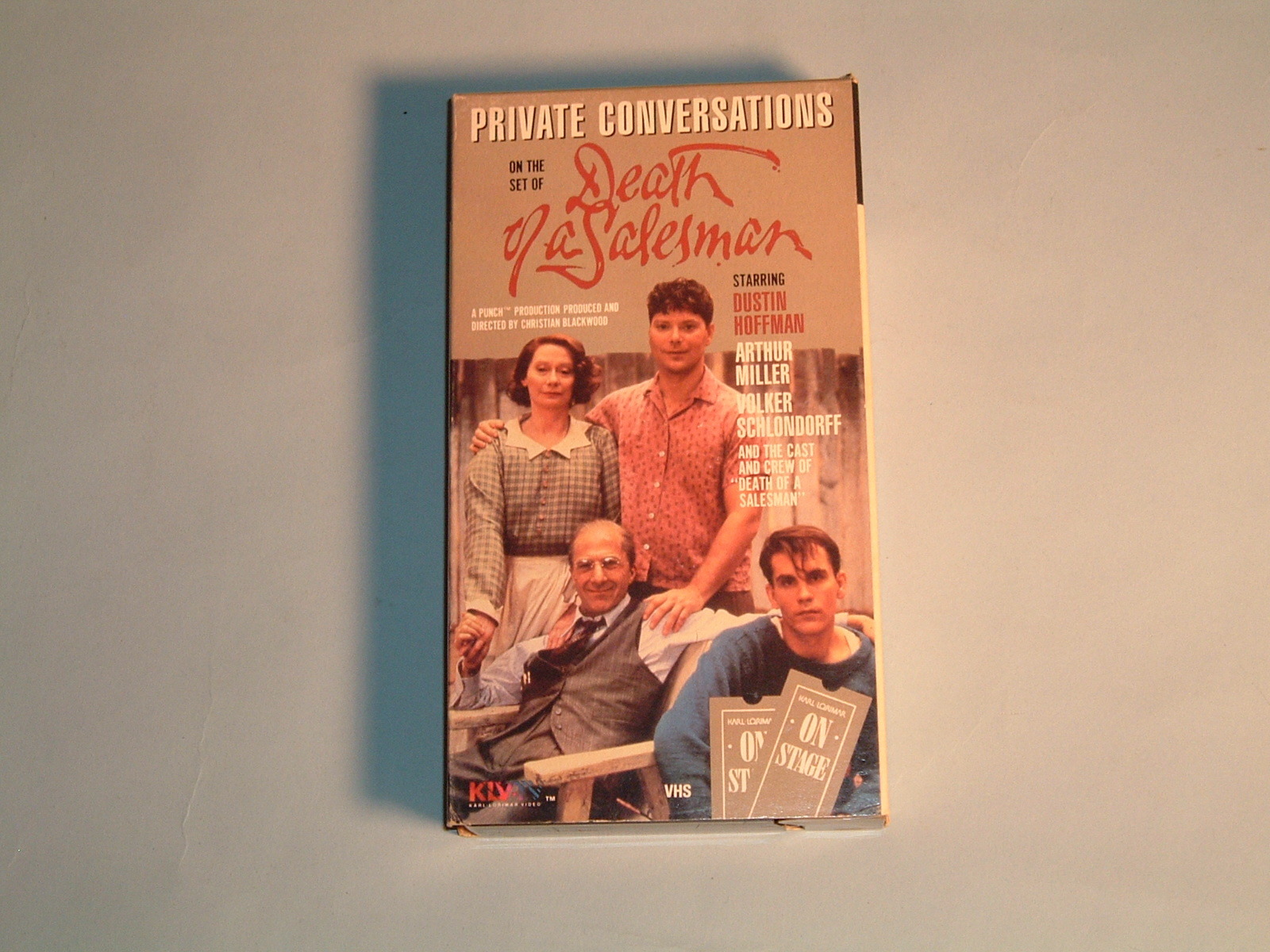

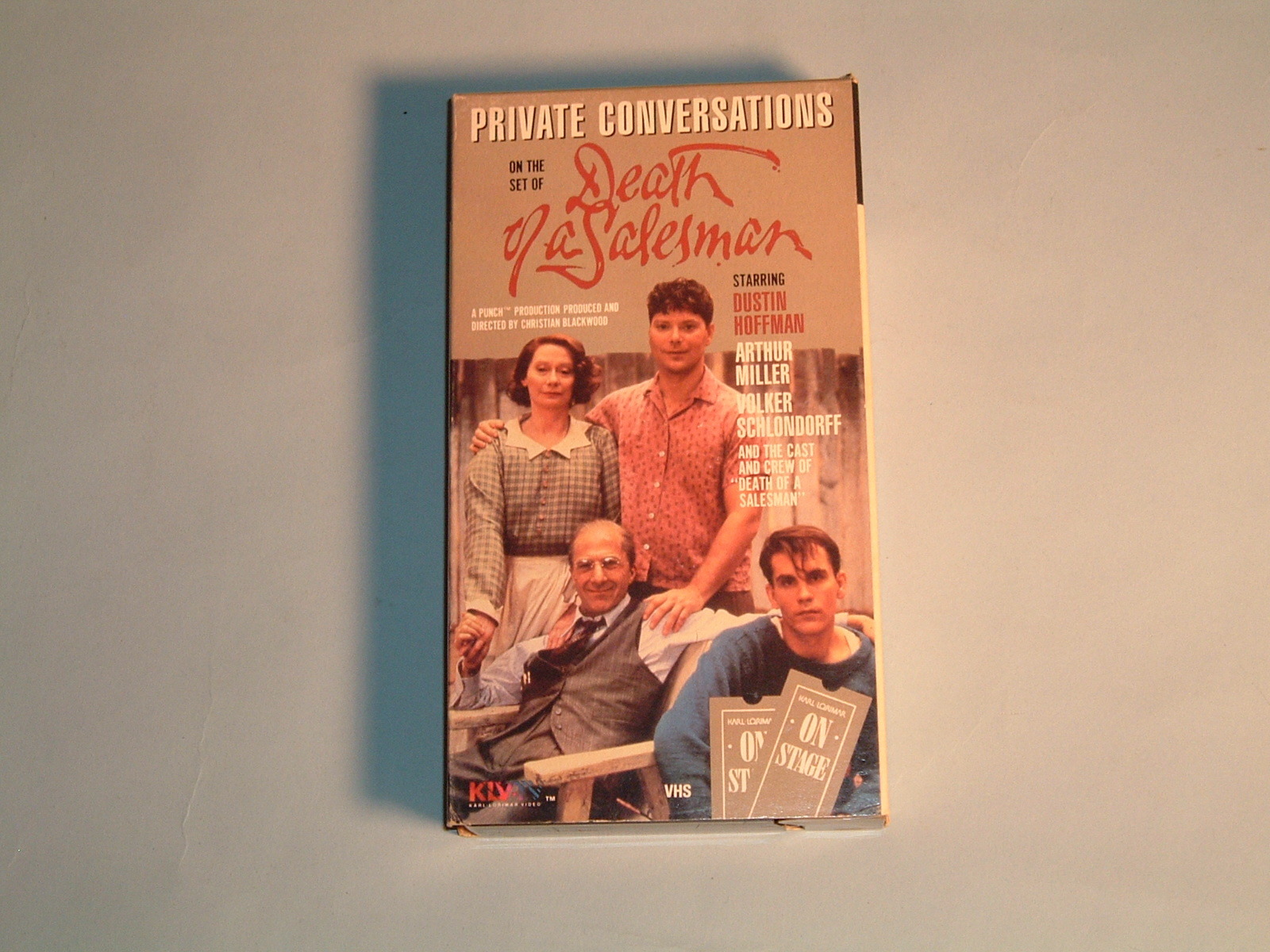

PRIVATE CONVERSATIONS: ON THE SET OF DEATH OF A SALESMAN

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Christian Blackwood.

I’ve never seen Volker Schlondorff’s 150-minute made-for-TV film of Death of a Salesman (1985), which Leonard Maltin’s TV Movies awards high marks: “Stunning though stylistic remounting of [Dustin] Hoffman’s Broadway revival of the classic Arthur Miller play with most of the cast from that 1984 production. A landmark of its type. Executive-produced by Hoffman and Miller. Hoffman and [John] Malkovich both won acting Emmys. Above average.” But a friend who has seen it, and who loves the play, tells me that she disliked the film: all the actors seemed to be off on their own tangents, she said, and there was little interplay between them.

Whether the Schlondorff film is good or bad, Private Conversations: On the Set of Death of a Salesman, the 82-minute documentary that Christian Blackwood made about the making of it, is endlessly fascinating, for reasons largely irrelevant to the worth of the Miller play or this particular production of it. Part of the open-endedness of Blackwood’s film comes from the fact that if Schlondorff’s film works the reasons are here, and if it doesn’t work the reasons are here — perhaps in the same circumstances. Read more

This appeared in the August 26, 1994 issue of the Chicago Reader. —J.R.

*** DIVERTIMENTO

(A must-see)

Directed by Jacques Rivette

Written by Pascal Bonitzer, Christine Laurent, and Rivette

With Michel Piccoli, Jane Birkin, Emmanuelle Béart, David Bursztein, Gilles Arbona, Marianne Denicourt, and the hand of Bernard Dufour.

NATURAL BORN KILLERS

(No stars–Worthless)

Directed by Oliver Stone

Written by David Veloz, Richard Rutowski, Stone, and Quentin Tarantino

With Woody Harrelson, Juliette Lewis, Robert Downey Jr., Tommy Lee Jones, Tom Sizemore, Rodney Dangerfield, Edie McClurg, Sean Stone, and Russell Means.

One of the more deceitful explanations for the compulsive repetition that informs most contemporary movies is that Hollywood is simply giving the public what they want. The idea that they even know what they want is pretty dubious to begin with — especially if one factors out all the publicity and hype that supposedly speaks for them. And the argument that moviemakers have any better sense of what the public wants is usually self-serving propaganda.

A more likely explanation for all the recycling is that it serves business interests — and contrary to what you read in Variety and Premiere, that is not necessarily the same thing as serving the public. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (May 1, 1991). — J.R.

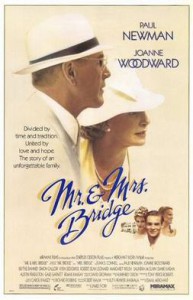

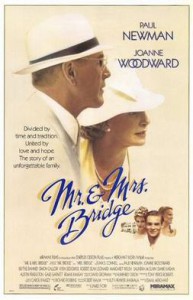

I’m not much of a James Ivory fan, but this 1990 adaptation of Evan S. Connell’s novels Mrs. Bridge (1959) and Mr. Bridge (1969) deserves to be seen and cherished for at least a couple of reasons: first for Joanne Woodward’s exquisitely multilayered and nuanced performance as India Bridge, a frustrated, well-to-do WASP Kansas City housewife and mother during the 30s and 40s; and second for screenwriter Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s retention of much of the episodic, short-chapter form of the books. It’s true that she and Ivory have toned down many of the darker aspects, but as critic Georgia Brown has suggested, Woodward’s humanization of her character actually improves on the original. Connell’s imagination and compassion regarding this character have their limits, and Woodward triumphantly exceeds them. There are other fine performances as well from Paul Newman (as uptight Mr. Bridge), Blythe Danner (as India’s troubled best friend), Simon Callow, and Austin Pendleton. If the Bridges’ three children are realized less acutely than their parents, the period portraiture nonetheless shows a great deal of taste and intelligence. With Kyra Sedgwick and Robert Sean Leonard. (JR)

Read more

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 1, 1991). — J.R.

An engaging, exciting noir thriller (1952) set almost entirely on a train going from Chicago to Los Angeles, with a gruff cop (Charles McGraw) guarding a saucy prosecution witness (the underrated Marie Windsor). Richard Fleischer directed this nearly perfect B picture with no fuss and lots of grit and polish from a script by Earl Fenton; the capable cinematography belongs to George E. Diskant. 70 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

For the Chicago Reader (August 23, 1991). Fortunately, I’ve been to Austin quite a few times since I wrote this review. — J.R.

Richard Linklater’s delightfully different and immensely enjoyable first feature takes us on a 24-hour tour of the flaky dropout culture of Austin, Texas; it doesn’t have a continuous plot, but it’s brimming with weird characters and wonderful talk (all of it scripted by Linklater, though it often seems improvised). The structure of dovetailing dialogues calls to mind an extremely laid-back variation on The Phantom of Liberty or Playtime. “Every thought you have fractions off and becomes its own reality,” remarks Linklater himself to a poker faced cabdriver in the first (and in some ways funniest) scene, and the remainder of the movie amply illustrates this notion with its diverse paranoid conspiracy and assassination theorists, serial-killer buffs, musicians, cultists, college students, pontificators, petty criminals, street people, and layabouts (around 90 in all). Even if the movie goes nowhere in terms of narrative and winds up with a somewhat arch conclusion, the highly evocative scenes give an often hilarious sense of the surviving dregs of 60s culture and a superbly localized sense of community. I’ve never been to Austin, but this movie certainly makes me want to pay a visit (1990). Read more

From the February 22, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

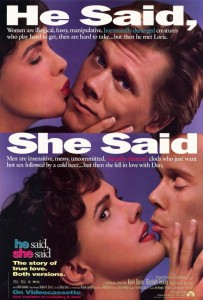

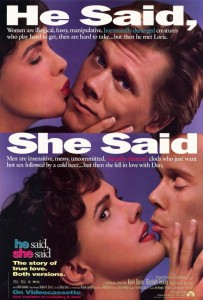

Try to imagine Siskel and Ebert not as Chicago film critics but as a heterosexual couple in Baltimore, both of them general interest reporters whose combative instincts and political and temperamental differences become the focus of a TV show, and you more or less have the premise of this romantic comedy. Kevin Bacon and Elizabeth Perkins play the leads, and a real-life couple (Ken Kwapis and Marisa Silver) direct the separate versions of their story (both scripted by Brian Hohlfeld). The attempt to tell the same story twice from separate viewpoints a la Rashomon or Les Girls doesn’t always yield as much ambiguity or complexity as one might wish. But on the whole, this is an honorable attempt to revive the feeling and ambience of a Hoilywood comedy of the 50s, complete with sumptuous romantic music (score by Miles Goodman), ‘Scope framing, and a magical last-minute resolution, and, as such, it’s pretty pleasurable to watch. With Sharon Stone. (Esquire, Norridge, Old Orchard, Webster Place, Ford City, Lincoln Village)

Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 1, 1996). — J.R.

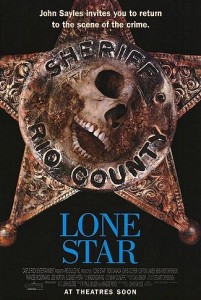

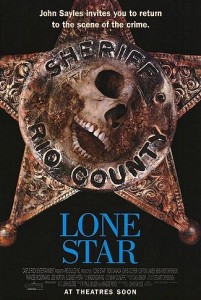

A well-constructed but rather unthrilling mystery thriller (1996) by John Sayles, filmed on location in a Texas border town, with a likable lead performance by Chris Cooper as a laid-back sheriff. The plot is intricate and ambitious, with nine other major characters (played by Elizabeth Peña, Kris Kristofferson, Miriam Colon, Frances McDormand, Joe Morton, Matthew McConaughey, Ron Canada, Eddie Robinson, and Clifton James), various flashbacks, and an exploration of history, corruption, racial persecution, and multiculturalism. The whole thing’s so worthy that I wish I liked it more. It makes time pass agreeably, but Square John still seems about as innocent of fresh ideas (aesthetically and otherwise) as most of his characters, and for this kind of leftist multiplot I found his City of Hope (1991) more engaging. Anecdotal aside: all the black extras in this movie had to be bused in for the filming. 134 min.

Read more

Read more

From the December 6, 1991 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

BLOOD IN THE FACE

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Anne Bohlen, Kevin Rafferty, and James Ridgeway

If memory serves, it was around my junior year in college, during the mid-60s, when a conservative classmate took my brother and me to a John Birch Society meeting in Hyde Park, New York, held inside a trailer in a trailer camp. The friend advised us to conceal our identities as liberal Jews (he was half Jewish himself) and try to blend in with the surroundings, which we did.

It was a sparsely attended meeting. Before that we made small talk with the handful of other people present — including the couple who owned the trailer and a young man who identified himself as the son of communists and who cheerfully explained that the society had deliberately adopted the structure of the Communist Party, complete with cell meetings like this one and vows of secrecy. He and everyone else in the room seemed friendly, normal everyday folks, until the film projector blew a fuse just as they began to screen a movie.

Then the paranoid speculations began: they made extensive flashlight searches of the yard around the trailer, looking for spies and saboteurs. Read more

From Sight and Sound (Winter 1990/91). -– J.R.

It’s no secret that serious film criticism in print has become an increasingly scarce commodity, while ‘entertainment news’, bite-size reviewing and other forms of promotion in the media have been steadily expanding. (I’m not including academic film criticism, a burgeoning if relatively sealed-off field which has developed a rhetoric and tradition of its own-the principal focus of David Bordwell’s fascinating recent book, Making Meaning) But the existence of serious film commentary on film, while seldom discussed as an autonomous entity, has been steadily growing, and in some cases supplanting the sort of work which used to appear only in print.

I am not thinking of the countless talking-head ‘documentaries’ about current features — actually extended promos financed by the studios or production companies — which include even such a relatively distinguished example as Chris Marker’s AK (1985), about the making of Kurosawa’s Ran. The problem with these efforts is that they further blur the distinction between advertising and criticism, and thus make it even harder for ordinary viewers to determine whether they are being informed about something or simply being sold a bill of goods. What I have in mind are films about films and film-makers which seriously analyse or document their subjects. Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader (September 16, 1994). — J.R.

**** THE BLUE KITE

(Masterpiece)

Directed by Tian Zhuangzhuang

Written by Xiao Mao

With Zhang Wenyao, Chen Xiaoman, Lu Liping, Pu Quanxin, Li Xuejian, Guo Baochang, Zhong Ping, and Chu Quanzhong.

Covering 15 years of modern Chinese history, from 1953 to 1968, The Blue Kite is powerful less for what it says about continuity in history than for what it implies about history disrupting people’s lives. The two things that matter most to Tietou, the fictional hero, apart from his mother, are the courtyard just off the Dry Well Lane apartment where his parents move in the opening scene and the title toy — actually a series of toys — he’s given to play with by his father. Each blue kite we see over the course of the film winds up getting stuck in one of the courtyard’s trees and needs to be replaced; more or less the same thing happens with the Tietou’s father (eventually supplanted by two stepfathers) and Tietou’s sense of home, not to mention his sense of identity. All that he retains, and only after a struggle, is a certain sense of morality bequeathed by his mother and a certain sense of place bequeathed by the courtyard. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 21, 1994); reprinted in Movies as Politics. “Special greetings to Jonathan Rosenbaum, who wrote a very perceptive note on THE LAST BOLSHEVIK,” Chris Marker kindly emailed John Gianvito a little over nine years ago. So I didn’t know how to respond to the news of his sad death, which occurred the day after his 91st birthday in 2012, except to reprint the note he was referring to, as well as a photo of the two of us the only time we met, at Peter von Bagh’s Midnight Sun Film Festival in Finland in 1998 — actually a blurry frame enlargement from Peter’s Sodankylä, Forever. — J.R.

***

**** THE LAST BOLSHEVIK

(Masterpiece)

Edited and written by Chris Marker.

It seems central rather than incidental to the art and intelligence of Chris Marker that he studiously avoids the credit “directed by . . . ” A globe-trotting French filmmaker whose only work of pure fiction with actors is a classic SF short consisting almost exclusively of still photographs (La jetée, 1962), he appears to avoid obvious fiction only in the sense that he finds actuality more than enough grist for the endlessly turning mill of his irony and imagination. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (September 4, 1998). — J.R.

Snake Eyes

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Brian De Palma

Written by David Koepp and De Palma

With Nicolas Cage, Gary Sinise, John Heard, Carla Gugino, Stan Shaw, Kevin Dunn, Michael Rispoli, Joel Fabiani, and Luis Guzman.

For me, part of the fun of Snake Eyes is the genuine satisfaction of seeing Brian De Palma finally arriving at his own level. Whatever the merits of his imitations and appropriations — of 50s Hitchcock in Dressed to Kill, Obsession, and Body Double, 60s Antonioni in Blow Out, and 30s Hawks in Scarface — and his inflations of TV standbys (The Untouchables, Mission: Impossible), they’ve always suggested he was riding into town on somebody else’s horse. Now, however, he seems more apt to make the 90s equivalents of B movies: such films as Raising Cain, Carlito’s Way, and Snake Eyes are generic stylistic exercises that reveal he’s digested his sources rather than simply devoured and regurgitated them. Though he remains too much of a mannerist to approximate the modest craft of Roy Ward Baker in Don’t Bother to Knock or Richard Fleischer in The Narrow Margin –– thrillers of 1952 that in their adept use of real time and limited settings suggest parallels withSnake Eyes — De Palma’s technique seems more focused for a change. Read more

Even though the following review for the Chicago Reader, originally published on March 27, 1998, is fairly mixed, it seems worth reviving as a reminder of how neglected significant portions of Charles Burnett’s work continue to be. I certainly wouldn’t mind seeing The Final Insult again and reconsidering it. (James Naremore gives it a thoughtful treatment in his excellent recent book on Burnett.)

It’s worth noting that When it Rains is now happily available on DVD, along with Killer of Sheep and My Brother’s Wedding, even though one has to look for it (its placement isn’t made clear on the jacket), on the two-disc set of Killer of Sheep, which also includes two separate versions of My Brother’s Wedding. —J.R.

The Final Insult

** Worth seeing

Directed by Charles Burnett

With Ayuko Babu and Charles Bracy.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

Given the difficulties he had in the 70s and 80s getting his films made and seen, Charles Burnett [see photo at end of article] seemed in danger of becoming the Carl Dreyer of the black independent cinema—the consummate master who makes a film a decade, known only to a small band of film lovers. Seven years passed between Killer of Sheep (1977) and My Brother’s Wedding (1984), and then another six before To Sleep With Anger (1990), which tried and failed to make a dent in the mainstream, as did The Glass Shield (1994). Read more

From the August 14, 1998 Chicago Reader.

The Son of Gascogne

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Pascal Aubier

Written by Patrick Modiano and Aubier

With Grégoire Colin, Dinara Droukarova, Jean-Claude Dreyfus, Laszlo Szabo, Pascal Bonitzer, Otar Iosseliani, Alexandra Stewart, and Jean-Claude Brialy.

It’s been a full quarter of a century, but I still harbor fond memories of a low-budget French comedy called Valparaiso Valparaiso, a first feature starring Alain Cuny and Bernadette Lafont that I saw at Cannes in 1973. A lighthearted satire about the myopia of romantic French revolutionaries, it details an elaborate hoax perpetrated on a befuddled leftist — a character so absorbed in the glory of departing for Chile to fight the good fight as a special agent that he doesn’t even notice the political struggle going on around him on the French docks when he leaves.

The film was so marginal that two years passed between its completion and its modest premiere at the Director’s Fortnight at Cannes, and you won’t find it mentioned in any of the standard reference books. No, I take that back: Jean-Michel Frodon gives it a third of a sentence in his over-900-page L’Age moderne du Cinéma Français de la Nouvelle Vague à nos jours (1995), linking it with two other films of the early 70s inspired by the French Communist Party and critical of leftists. Read more

From the November 1, 1999 Chicago Reader. — J.R.

Quentin Tarantino’s cameraman, Lebanese filmmaker Ziad Doueiri, wrote and directed this autobiographical first feature (1998) about his early teens in Beirut — set in 1975, during the onset of the country’s civil war — and cast his younger brother Rami as himself. In fact, Doueiri scores with every member of his wonderful cast, which consists of nonprofessionals in the child roles and seasoned veterans playing the grown-ups. This is one of the best coming-of-age movies I’ve seen, largely because the characters are so full-bodied and believable without falling into predictable patterns. The excellent score is by Stewart Copeland. In French and Arabic with subtitles. 105 min. (JR)

Read more