This review, featured on the cover, appeared in the December 1985 issue of Video Times. I was living in Santa Barbara at the time, and not long after it came out, I met Joe Dante for the first time, in Los Angeles (at a party given by Todd McCarthy); he’d recently read this review, and, as I recall, told me that he liked it. — J.R.

Gremlins ***

As a producer and director, Steven Spielberg seems limited to two subjects: power and magic. The power that interests him is, of course, the power that he commands, and the magic is that of his medium. Put these together and add the input of director Joe Dante, another film buff, and you get a movie about movies, triple-distilled. And the curious achievement of Gremlins is that it makes such self-absorption commercially viable, at the same time that it refuses to conform to any single, sustained social meaning. Much as the depiction of Vietnam in Coppola’s Apocalypse Now was designed to placate hawks and doves alike, gremlins is cleverly contrived to please skeptics as well as believers, optimists as well as pessimists about the American way of life. Thanks to a disconnected episodic structure that suggests several separate movies crammed together — a strategy that re-creates the fragmented, discontinuous flow of TV watching — viewers of Gremlins are invited to chart out their own justifications for enjoying Dante and Spielberg’s treasure trove. Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader on April 26, 1991. Consider this review Part 2 of a long-term re-evaluation of Alan Rudolph’s use of music and his treatment of working-class people, preceded by my 1979 review of Remember My Name for Film Quarterly. — J.R.

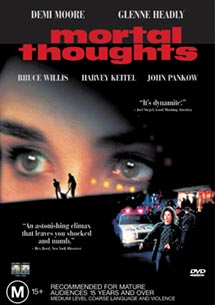

MORTAL THOUGHTS

** (Worth seeing)

Directed by Alan Rudolph

Written by William Reilly and Claude Kerven

With Demi Moore, Glenne Headly, Bruce Willis, Harvey Keitel, John Pankow, and Billie Neal.

For all his talent and sophistication, Alan Rudolph has frequently shown a romantic slant toward the working class that borders on stylistic gentrification. Even in my two Rudolph favorites, Remember My Name (1978) and Choose Me (1984), the ironic casting of a construction worker and his wife with real-life mod couple Anthony Perkins and Berry Berenson and the creation of a dream-bubble ambience in a gritty bar suggest a kind of put-on.

Life is a dream, Rudolph always appears to be saying, and the more sordid and low-down the life is, the more seductive and precious the dream becomes. It’s a viable enough premise for a mannerist, and he invariably makes the most of this conceit; yet there are times when his taste for cardboard funk causes his worlds to totter like houses of cards. Read more

This appeared in the August 27, 1999 issue of the Chicago Reader. –J.R.

The Muse

Rating ** Worth seeing

Directed by Albert Brooks

Written by Brooks and Monica Johnson

With Brooks, Sharon Stone, Andie MacDowell, Jeff Bridges, Mark Feuerstein, Stacey Travis, and Steven Wright.

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

The Muse made me laugh, but not as much as the five Albert Brooks movies preceding it. It also made me think less, and that’s more of a problem. I don’t care whether Mel Brooks makes me think, but Albert’s a different matter. He’s a conceptual filmmaker unlike any other — a Stanley Kubrick among comedians whose premises need to be pondered, not simply accepted or rejected.

The Muse is a somewhat flimsy high-concept movie whose ultimate justification is that its subject is the manufacture of flimsy high-concept movies. It isn’t so much about a muse as about the apparent need for one. Steven Phillips (Brooks) is a well-to-do Hollywood screenwriter with a wife (Andie MacDowell) and two daughters — the first Brooks hero to have children — who’s desperate because everyone tells him he’s “lost his edge.” What does that mean? The movie doesn’t say, and Brooks, as usual, doesn’t spell it out. Read more

The following appeared in the Chicago Reader on January 16, 2004. Over five years later, I developed some elements in this piece while writing a much longer account of Thompson’s work including an email exchange with him which appeared in the Fall 2009 issue of Film Quarterly. (See “A Handful of World”.)

I was more than gratified when Thompson told me, years later, that this review led him to go back on his decision to retire from filmmaking and make another film, which yielded Lowlands, a few years before his untimely death. — J.R.

Universal Hotel

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed and written by Peter Thompson.

El movimiento

*** (A must-see)

Directed by Peter Thompson

Written by William F. Hanks and Thompson.

Peter Thompson, who teaches photography at Columbia College and makes personal, autobiographical documentaries, is a major, neglected filmmaker. He’s made five films, and the latest, El Movimiento, his only feature, is having its world premiere at the Gene Siskel Film Center on January 16 and will be shown there again on January 19 — both times with the 1986 Universal Hotel, my favorite of Thompson’s shorts. (Thompson will lead a discussion at the Friday screening.)

Philosophically and aesthetically, Thompson’s films are as beautiful and provocative as any contemporary American independent work that comes to mind. Read more

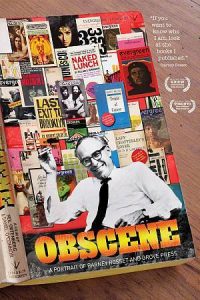

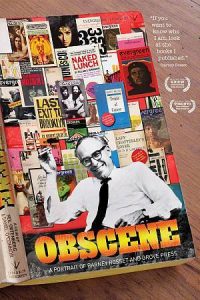

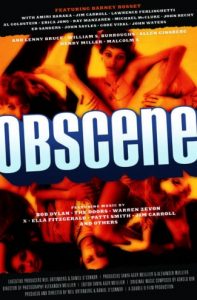

From the October 30, 2009 Chicago Reader. I was delighted to learn that Barney Rosset (1922-2012) Iiked this review. — J.R.

A tiresome film on an interesting subject, this 2007 documentary jives with fancy graphics and pop golden oldies as it profiles Barney Rosset, editor and publisher of the often scandalous Grove Press and Evergreen Review. The man who helped launch the career of Samuel Beckett is quickly overtaken by the one who operated a Soho literary salon while profiting as a porn merchant, and apart from noting Rosset’s wealthy Jewish-Irish origins, video makers Daniel O’Connor and Neil Ortenberg don’t give us much to differentiate him from someone like Hugh Hefner. A cable-TV interview of Rosset by Screw publisher Al Goldstein is given as much prominence as Rosset’s 1937 home movies of his trip through Europe, which suggests that swagger matters more than history or culture. There are more stupid sound bites than smart ones, but the directors don’t seem to care which is which. 97 min. (JR)

Read more

Read more

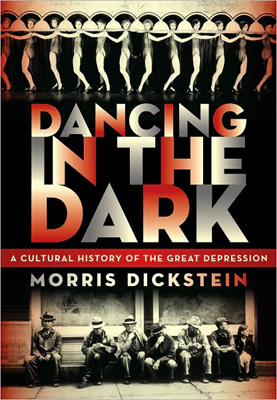

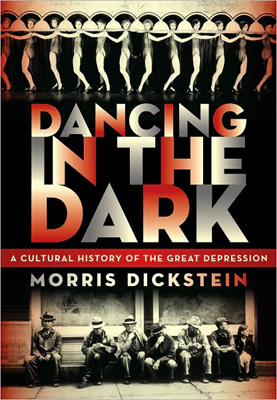

Recommended Reading: DANCING IN THE DARK: A CULTURAL HISTORY OF THE GREAT DEPRESSION by Morris Dickstein, New York/London: W.W. Norton & Company, 2009, 598 pp.

How refreshing it is to encounter a treatment of Busby Berkeley’s Depression musicals as something other than escapism — as genuine engagements with their own period and audience. Part literary criticism, part film and art criticism, part history of popular as well as intellectual culture, Morris Dickstein’s magnum opus is full of sensible revisionist observations of this kind to counter received wisdom, and it’s always a pleasure to read. Even if he doesn’t always accord full justice to the ideological and ethical underpinnings of some Depression novels (I’m perhaps the only one on the planet who regards Faulkner’s 1932 Light in August, my supreme favorite, as a communist novel, at least existentially), Dickstein is almost always deepening my understanding of whatever he happens to be writing about. [9/28/09] Read more

While I was in Vienna in October 2009, helping to launch my film series “The Unquiet American: Transgressive Comedies from the U.S.,” Der Standard commissioned the following article from me. Since they didn’t run it, I decided to post it here, spurred in part by an excellent article by David Walsh on a related subject that Christa Fuller brought to my attention.

To update my concerns to the present, one might substitute condemnations of Woody Allen and/or Ronan Farrow to those of Roman Polanski and his accusers, which are currently being treated in the press and social media at times as more important than the crimes of, say, Donald Trump or Vladimir Putin. — J.R.

Roman Polanski and The Catastrophe of Public Discourse

By Jonathan Rosenbaum

The recent arrest of Roman Polanski in Switzerland, on charges for fleeing to France 31 years earlier before standing trial for illegal sexual intercourse with a 13-year-old girl, was obviously a notable news item. But that alone could hardly have accounted for the indignant outcries from the American press and blogosphere about the nature of Polanski’s crime and the justice of his arrest.

Why should the case of Polanski be considered more relevant to the present moment than the multiple war crimes of Dick Cheney, for instance? Read more

This appeared in the Chicago Reader (February 21, 1992), and is reprinted in my 1997 collection Movies as Politics. — J.R.

RHAPSODY IN AUGUST

*** (A must-see)

Directed and written by Akira Kurosawa

With Sachiko Murase, Hisashi Igawa, Mie Suzuki, Tomoko Ohtakara, Mitsunori Isaki, Hidetaka Yoshioka, and Richard Gere.

Next month, Akira Kurosawa will be celebrating his 82nd birthday. Having long outlived the two other supreme masters of the Japanese cinema — Kenji Mizoguchi, who died in 1956, and Yasujiro Ozu, who died in 1963 — he bears the handicap of living on in an era that clearly seems remote and alien to him, despite the fact that his work has enjoyed much more currency in the 80s and early 90s than that of any of his near-contemporaries.

I’ve always been somewhat slow to appreciate the mastery of Kurosawa in relation to the works of Mizoguchi and Ozu, perhaps in part because I started off on the wrong footing. The first Kurosawa film I ever saw was Rashomon (1950), the single movie that was most responsible for introducing the western world to the Japanese cinema, and, as it happens, I saw it as a teenager only after reading the two short stories by Ryunosuke Akutagawa that it was based on. Read more

It’s obvious by now that David Thomson is never going to relinquish his unwarranted and unvarying baseline assumption about Orson Welles (see his column in today’s Guardian) that he was a failure whose life and career consisted of nothing but “decline”. Why? Because what Thomson means by success is precisely what he’s achieved himself: uncontroversial popularity and acclaim, taking popular and comforting positions that irritate no one except for a few diehards like me. If failure actually means failure to tell people what they already think and failure to support what they already believe, then I can only agree — Welles was a failure through and through. Unlike Thomson, a glorious success whose career can be described only as continuous ascent into the stratosphere. If only Welles could have turned himself into a David Thomson, goes the apparent assumption, then everybody would be happy. [10/23/09]

Postscript (10/25/09]: In a state of relative calm, I’ve just reread Thomson’s column, and can see that, okay, he’s trying to imply that Welles might have conceivably been happy when he died even without having millions in the bank. Fair enough. But his insufferable pose of pseudo-knowingness about matters he knows little or nothing about, which also suffuses every page of his Welles biography, continues to gall me.”He Read more

Posted Fri, Dec 8, 2006 at 11:21 AM

It’s interesting to see how some of the most difficult and challenging examples of art cinema have become increasingly popular over the past decade. Back in the 60s and 70s, Robert Bresson was virtually a laughing-stock figure to mainstream critics, and someone whose films characteristically played to almost empty houses. Yet by the time that he died, a retrospective of his work that circled the globe was so successful in drawing crowds that in many venues—including Chicago’s Film Center — it had a return engagement. Much the same thing has happened with Andrei Tarkovsky — another uncompromising spiritual filmmaker, and one whose films are even tougher to paraphrase or even explain in any ordinary terms.

I’m just back from a trip to the east coast where I was gratified to find, when I turned up to introduce a screening of Jacques Rivette’s 252-minute L’amour fou (1968) in Astoria’s Museum of the Moving Image, that the film was playing to a nearly packed house. (Incidentally, this galvanizing love story about the doomed relationship between a theater director and his wife, played by Jean-Pierre Kalfon and Bulle Ogier, has never looked better to me, though I’ve been a big fan since the early 70s.) Read more

This was my second posting for the Chicago Reader blog post, although it might have been the first one I wrote (and the second to have been edited) — I can no longer remember for sure. –J.R.

Film history that is open to the present

Tue, Nov 14, 2006 at 4:07 PM

Last month Alexander Horwath, director of the Austrian Film Museum, sent me a press release about an ambitious and audacious retrospective he’s presenting throughout November entitled “Notre Musique,” devoted to “forty major works of fictional and documentary cinema made between 2000 and 2006.” “Film museums are often — and justifiably — viewed as places where an awareness of the historic foundations of contemporary cinema can evolve,” he begins. “Yet a reverse perspective is equally important — an approach to film history that is open to the present.” His selection, he adds, “is not so much influenced by the best-known or `most-discussed’ films of recent years but rather by the unbroken capacity of cinema to bear witness to life on this planet [his emphasis] — not just in the sense of documentation but also as an illumination of circumstances that habor a potential for change.” What he’s put together, in short, is a group of films that are supposed to bear witness, politically and responsibly, to the present moment — a daring gesture if one considers Jacques Rivette’s plausible statement in a Cahiers du Cinéma roundtable over 40 years ago, that it’s virtually impossible for a critic to know the long-term value of a film when it first appears. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, July 27, 1990. –J.R.

THE FRESHMAN

*** (A must-see)

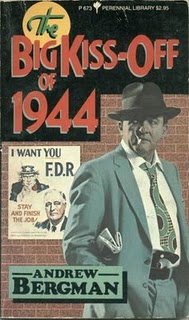

Directed and written by Andrew Bergman

With Matthew Broderick, Marlon Brando, Bruno Kirby, Penelope Ann Miller, Frank Whaley, Maximilian Schell, and Bert Parks.

“The overwhelming attractiveness of the screwball comedies involved more than the wonderful personnel. It had to do with the effort they made at reconciling the irreconcilable. They created an America of perfect unity: all classes as one, the rural-urban divide breached, love and decency and neighborliness ascendant. –Andrew Bergman, We’re in the Money (1971)

Most reviews of The Freshman have understandably focused on Marlon Brando. After all, everybody knows Brando, while hardly anyone is familiar with Andrew Bergman, the writer-director. But a movie as outlandish as this needs to be seen in some sort of context if one is going to make any sense of it, and it seems to me that Bergman is more important to this context than Brando is. It was his script, after all, that lured Brando into his first major role in a decade.

Bergman was born in Queens, the son of a New York Daily News radio and TV columnist named Rudy Bergman, and was an early fan of TV comics like Ernie Kovacs, Victor Borge, and Bob and Ray. Read more

This appeared as the lead article in the May-June 1974 issue of Film Comment — a somewhat pared-down revamping of my entry about Stroheim for Richard Roud’s belatedly published Cinema: A Critical Dictionary (New York: The Viking Press, 1980), and, if memory serves, the longest of my several contributions to that long out-of-print collection. — J.R.

Second Thoughts on Stroheim

by Jonathan Rosenbaum

Preface

Total object, complete with missing parts,

instead of partial object. Question of degree.

— Samuel Beckett, “Three Dialogues”

Two temptations present themselves to any modern reappraisal of Erich von Stroheim’s work; one of them is fatal, the other all but impossible to act upon. The fatal temptation would be to concentrate on the offscreen image and legend of Stroheim to the point of ignoring central facts about the films themselves: an approach that has unhappily characterized most critical work on Stroheim to date. On the other hand, one is tempted to look at nothing but the films — to suppress biography, anecdotes, newspaper reviews, reminiscences, and everything else that isn’t plainly visible on the screen.

Submitting Stroheim’s work to a purely formal analysis and strict textural reading of what is there — as opposed to what isn’t, or might, or would or could or should have been there — may sound like an obvious and sensible project; but apparently no one has ever tried it, and there is some reason to doubt whether anyone ever will. Read more

This essay, published in Film Comment in September-October 1976, represented one particular round in a series of initiatives and polemical forays I conducted on behalf of Jacques Rivette’s Duelle, which included getting it into the Edinburgh International Film Festival that year (and then writing about that festival at length in the Winter 1976/77 issue of Sight and Sound). One part of my effort was to engage the attention and interest of writers associated with the English theoretical magazine Screen, and this portion of the effort mainly failed: the principal response of the Screen writers who bothered to see it, as I recall in terms of their comments to me, was that it was basically warmed-over Cocteau and/or Franju — a reaction that I consider now, as I did then, to be rather obtuse and philistine. On the other hand, I no longer relish Duelle with quite the same fervor that I did at the time, even though there are certain moments in Jim Jarmusch’s very pleasurable The Limits of Control, that remind me of it. (Nowadays I prefer L’amour fou, both versions of Out 1, and Celine and Julie Go Boating — for me the peaks of Rivette’s work.) Read more

This appeared in The Soho News on March 11, 1981. A month earlier, I had launched a kind of weekly column there called “Declarations of Independents” that was in diary form — a bit like some of my Paris Journals and London Journals for Film Comment during the 70s –- and this was the third of these. — J.R.

Feb. 24: Why go all the way to the Thalia tonight to see five Screen Directors Playhouse episodes, all half-hour TV shows from the mid-50s? Two professional reasons spring to mind, both essentially recycling operations. As often happens in such cases, I feel myself split between the two — processes that honor my asocial aesthetics on the one hand, my social politics on the other.

Auteurist Retrieval technology (we’ll call it ART for short) — cultivated by me and a lot of other film freaks in the late 60s — is predicated on the pleasure of recognizing the taletale signs of favorite directors in all sorts of unlikely material. And what better excuse to put ART to work than patriarchal episodes by John Ford, Leo McCarey, Frank Borzage, Tay Garnett, and William Seiter? Indeed, to narrow the focus down to the evening’s main event, what better specimen could one hope to find but a crisp 35mm print of Ford’s Rookie of the Year, made immediately before his masterpiece The Searchers, with the same scriptwriter (Frank Nugent) and no less than four of the same actors — John Wayne, Pat Wayne, Vera Miles and Ward Bond — playing central roles? Read more