Writer-director Michael Roemer’s only well-known feature previous to this was the skillful Nothing but a Man (1964), about the experiences of a black couple living in Alabama. The Plot Against Harry was shot in black and white in 1969 but neither completed nor shown until 1989. A delightful, offbeat comedy, it follows a sad-eyed, small-time New York numbers racketeer named Harry Plotnick (Martin Priest) who has just emerged from prison after many years. Finding that life has passed him by, he gamely tries to buy his way into middle-class respectability, though his wife despises him and he’s a total stranger to his kids. In the course of conducting business, he passes through a picaresque succession of locations and noisy events — bar mitzvah, fashion show, dog-training session, and an endless stream of parties — yet the movie’s pace is leisurely, the humor quiet and affectionate, in striking contrast to the brassy world Harry moves through. Beautifully shot (by coproducer Robert M. Young, a director in his own right) and featuring a wonderful cast of unknowns (including Ben Lang, Maxine Woods, Henry Nemo, Jacques Taylor, Jean Leslie, Ellen Herbert, and Sandra Kazan), this is both a lovely piece of filmmaking and an exquisitely detailed portrait of a milieu and period, like a time capsule recently opened. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 5, 1990). — J.R.

As a moviegoer who was privileged to see a good many films, both new and old, in a number of contexts, places, and formats in 1989, I can’t say it was a bad year for me at all. I saw two incontestably great films at the Rotterdam film festival (Jacques Rivette’s Out 1: Noli me tangere and Joris Ivens and Marceline Loridan’s A Story of the Wind), and several uncommonly good ones both there and at the festivals in Berlin, Toronto, and Chicago. (Istvan Darday and Gyorgyu Szalai’s The Documentator and Jane Campion’s Sweetie — the latter due to be released in the U.S. early this year–are particular standouts.) Thanks to the increasing availability of older films on video, I was able to catch up with certain major works that I’d missed and see many others that I already cherished.

But considering only the movies that played theatrically for the first time in Chicago, I have to admit that it was a discouraging year. In fact, 1989 was the worst year for movies that I can remember, particularly when it comes to U.S. releases. Gifted filmmakers are granted less and less freedom as the Hollywood studios are taken over by conglomerates and European films are set up as international coproductions — both trends that have been in process for some time now; and the grim consequences of these changes become much more apparent when one takes a long backward look rather than when one considers the immediate surface effects of movies on a week-by-week basis. Read more

The following text, a late addition to this web site, was copied almost verbatim (apart from the correction of typos) from the laptop of the late Peter Thompson, thanks to the help of his widow, Mary Dougherty. — J.R.

Jonathan Rosenbaum, “Talking to Strangers: A Look at Recent American Independent Cinema”, ARTPAPERS, Vol. 13, No. 5, September/October 1989, pp. 6-10.

The following article is excerpted from a lecture given on June 15, 1989 in Lisbon, Portugal, at a seminar organized for the Luso-Americanos de Arte Contemporanea at the Fundacao Calouste Gulbenkian to introduce screenings of a dozen recent American independent films selected by Richard Peña and myself. Peña and Jon Jost also gave lectures at the same seminar — the former offered a broad history of independent filmmaking in the U.S., while the latter gave a subjective account of his own experiences as an independent filmmaker — followed by interventions from Portuguese critics.

It is virtually impossible to treat recent American independent film as a unified, homogeneous body of work. While there has been an unfortunate tendency in academic criticism to treat Italian neo-realism. the French nouvelle vague, or Hollywood films during any particular decade as if they had homogeneity and unity, such an effort can be made only if one views the work incompletely and superficially, and this is perhaps even more true with an unwieldy category such as American independent film. Read more

Written for Cineaste (I forget which issue).

Letters from Hollywood:

1977-2017

by Bill Krohn. Albany: State University of New York Press, 2020. 312 pp., illus. Hardcover: $95.00.

Long overdue, this impressive if pricey collection by the long-standing —indeed, longest-standing — American correspondent for Cahiers du cinéma is eclectically divided into four sections. After an Introduction consisting of a new five-page memoir (“How I Became the Los Angeles Correspondent for Cahiers du cinema”), a fascinating 25-page interview with Serge Daney (then the magazine’s editor) from 1977, entitled “The Tinkerers”, and a brief 1992 obituary for Daney, one encounters “Directors Who Started in Silents” (ten essays), “Directors Who Started in Talkies” (seven essays), “Directors Who Started in Television” (seven essays), and “Directors Who Counterattacked” (ten essays).

These classifications can’t do justice to all that the book has to offer: even if one can puzzle out what Krohn means by “counterattack,” the first “director” he treats who “started in television” is Lucille Ball, justly celebrated for I Love Lucy rather than as a director, and someone whose career as a performer, as Krohn shows, actually began in theater, movies, and radio. But they do point up how original Krohn’s way of positioning himself often turns out to be. Read more

From the Soho News (August 20, 1981). — J.R.

Film India: Indian Film Festival Museum of Modern Art, through August 23

Buster Keaton Film Festival Lincoln Plaza, through September 19

Directed for Comedy Regency, through October 17

Honky Tonk Freeway Written by Edward Clinton

Directed by John Schlesinger, opens August 21

AUGUST 7: The first movie I see for this column isn’t a light comedy, but it sure puts me in a sunny mood. The prospect of a three-hour Indian film in Temil with no subtitles is a little off-putting, I would say -– wouldn’t you? On my way into the sparsely populated auditorium of the Museum of Modern Art this afternoon, I hear not one but two separate senior citizens crack jokes about what a nice opportunity this is for a nap.

And yet, just as Indian film buff Elliott Stein has predicted, I have surprisingly little trouble following the plot and action of Chandralakha (1948). The quaintly illusionistic charm of a black-and-white movie like this, about a good and bad brother vying for the throne in a mythical kingdom – with a large palace protected by a drawbridge –- is part of its primal pull from the beginning. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (January 6, 1995).

Many friends and colleagues have been moaning about what a bad year 1994 was for movies, but I disagree. The main issue, I think, isn’t so much how we feel about the same movies — though there are a few differences there, including in some cases where and when we happened to see them — as it is what we saw. If you’re lucky enough to be living in Chicago, you had loads of terrific movies to see last year, new as well as old, and if you didn’t see very many of them, it’s possible that you were looking in the wrong places — where the mass media was telling you to look. Because of their running times, my two favorite films, the seven-hour Satantango and the nearly 26-hour The Second Heimat, received only limited exposure, yet I refuse to accept the standard alibi of most critics who neglected to see them — that they were too difficult or esoteric for the general public. I found them easier to sit through and vastly more involving and pleasurable than such overhyped and overattended European monoliths as Germinal and Queen Margot, which to the best of my knowledge gave little enjoyment to most people. Read more

Written for the British Film Institute’s DVD release of this film in early 2011. — J.R.

It would hardly be an exaggeration to call A Hen in the Wind (1948) one of the more neglected films of Yasujiro Ozu, especially within the English-speaking world. Made immediately before one of his key masterpieces, Late Spring (1949), it has quite understandably been treated as a lesser work, but its strengths and points of interest deserve a lot more attention than they’ve received. It isn’t discussed in Noël Burch’s To the Distant Observer: Form and Meaning in the Japanese Cinema (1979) or even mentioned in Kyoko Hirano’s Mr. Smith Goes to Tokyo: Japanese Cinema under the American Occupation, 1945-1952 (1992), the English-language study where it would appear to be most relevant. Although it isn’t skimped in David Bordwell’s Ozu and the Poetics of Cinema (1988), its treatment in Donald Richie’s earlier Ozu (1974) is relatively brief and dismissive. It seems pertinent that even the film’s title, which I assume derives from some Japanese expression, has apparently never been explicated in English.

It may be an atypical feature for Ozu, but it is stylistically recognizable as his work from beginning to end, especially when it comes to poetic handling of setting (a dismal industrial slum in the eastern part of Tokyo, where the heroine rents a cramped upstairs room in a house) and its use of ellipsis in relation to the plot. Read more

This appeared in the May 5, 1995 issue of the Chicago Reader. — J.R.

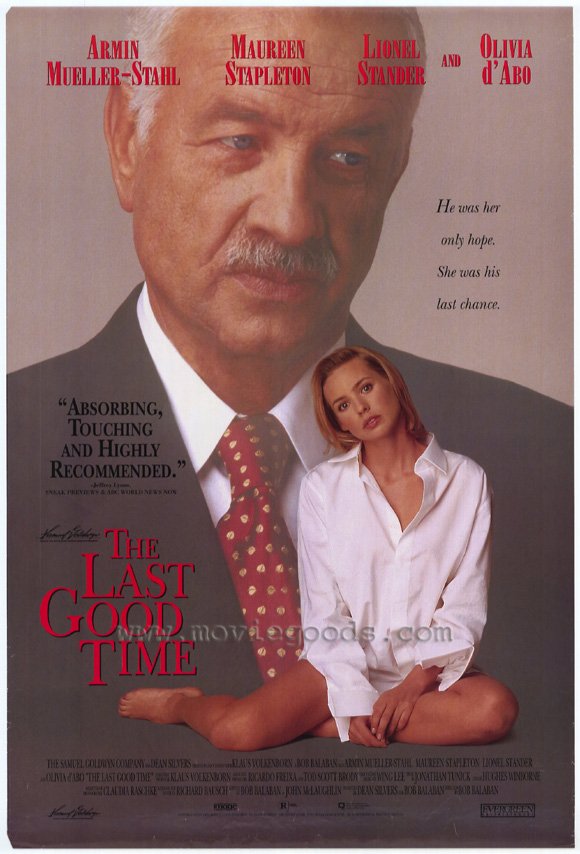

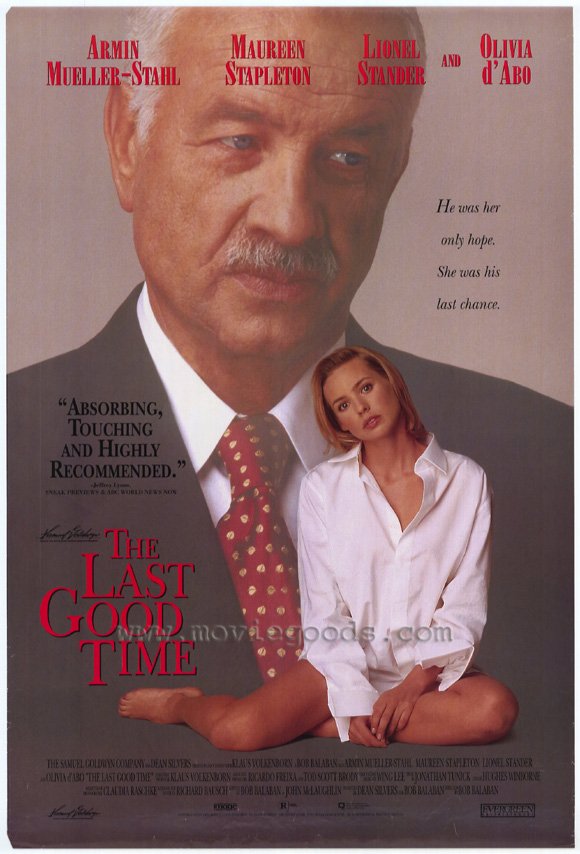

The Last Good Time

Rating *** A must see

Directed by Bob Balaban

Written by Balaban and John McLaughlin

With Armin Mueller-Stahl,Olivia d’Abo, Lionel Stander,Maureen Stapleton, Kevin Corrigan, Adrian Pasdar, and Zohra Lampert.

Bob Balaban, a native Chicagoan who’s best known as a prolific movie and stage actor, has directed only three features to date. I haven’t seen his second feature, My Boyfriend’s Back (1993), which some people tell me I’m better off having missed, but Parents, his first, was one of the most auspicious debuts of 1989.

Despite the radical differences between Parents and The Last Good Time in terms of genre, subject, style, and tone, they’re clearly the work of the same filmmaker. Part of this has to do with a precise feeling for place and a profound grasp of what sitting alone in a room feels like, even when other people are present. The solitary character in Parents is a ten-year-old boy who’s living with his parents in tacky 50s American suburbia. The monstrous (if typical) ranch-style house where they live is seen basically just as the boy experiences it — an expressionist, wide-angle nightmare etched in “cherry pink and apple blossom white” (to quote the song heard over the opening credits) that matches his parents’ taste and hypocrisy. Read more

From the Chicago Reader, April 21, 1995. It’s lamentable that, although Black Girl is now available on DVD from New Yorker, the color sequence in it appears in black and white. (In fact, I only saw this sequence in color for the first time when I showed this film in a course on world cinema of the 60s that I taught in Chicago in 2008.) To see this sequence in color, order the film’s BFI edition from Amazon UK. — J.R.

Black Girl

Rating **** Masterpiece

Directed and written by Ousmane Sembène

With Mbissine Thérèse Diop, Momar Nar Sene, Anne-Marie Jelinck, Robert Fontaine, Ibrahima Boy, and the voices of Toto Bissainthe, Robert Marcy, and Sophie Leclerc.

If you trace African film back to its first fiction feature, it is only 30 years old. Yet far from being underdeveloped, it begins on a more sophisticated level than any other cinema in the world. By some accounts Ousmane Sembène’s hour-long Black Girl was made in 1965, by others 1966, a characteristic ambiguity when it comes to African movies. Do you date them according to when they were made or when they were first shown? And given the scant and largely unreliable print sources that we have to check, how can we be sure about either date? Read more

From Cinema Scope #14 (Spring 2003). It’s interesting to note that many of the releases that I discuss here are still available, if not always readily available. All of my recent columns, by the way, starting with issue #40, can be found on Cinema Scope‘s web site. — J.R.

A FEW PRELIMINARIES. The word is still getting out about the riches that are currently available to cinéphiles owning DVD players that play discs from all the territories —- players that are by now readily available at affordable prices to anyone with enough initiative to go looking on the Internet. But it might be added that the number of previously scarce films that can now be purchased in North American Territory is already quite substantial.

Combine these two opportunities and you have the pretext for a new column, which will be devoted not to DVD players (that’s your problem) but to DVDs that are currently available. This will follow the capitalistically incorrect premise that once you move beyond your own designated territory, the world becomes your oyster and a different sort of place from the one that assumes that you’re necessarily trapped as a consumer by the choices offered within your own national borders. Read more

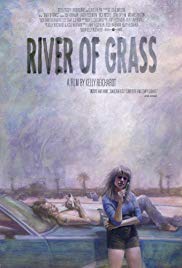

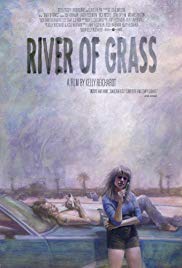

From the September 1, 1995 Chicago Reader. I was shocked to discover that this is the only Kelly Reichardt film I ever reviewed in the Reader. Having just seen the amazing First Cow for the first time, I can’t understand how I ever allowed this to happen. If you decide to voyage out anywhere during the coronavirus lockdown, you can’t afford to miss this mysterious mind-bender and the singular world it simultaneously creates and discovers. — J.R.

A canny, contemporary portrait of shiftlessness, this adept first feature (1993) by American independent Kelly Reichardt, set in the Florida Everglades, is about people so bored they jump at the chance to go on the lam — taking off even before they’ve committed a crime. Reichardt has an original sense of how to put together a film sequence and an effective way of guiding her cast of unknowns through an absurdist comedy of errors. With Lisa Bowman, Larry Fessenden, Dick Russell, Stan Kaplan, and Michael Buscemi. (JR)

Read more

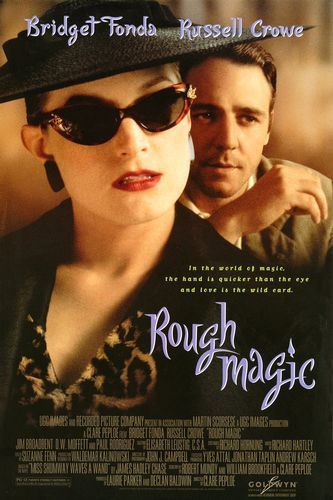

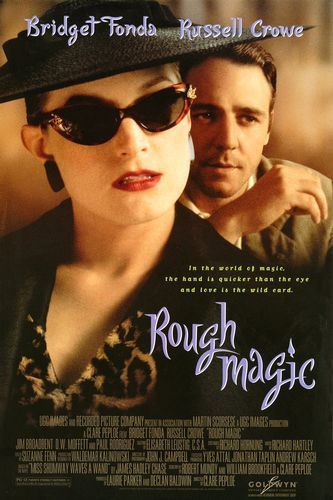

A Critic’s Choice for the Chicago Reader (June 6, 1997). — J.R.

In an era when the only fantasies grown-up critics are supposed to validate are preschool ones, here’s a charming and decidedly offbeat adult fantasy-comedy (1995) from the stylish English director Clare Peploe (High Season). In the early 50s, around the time of Nixon’s Checkers speech, a magician’s apprentice (Bridget Fonda) who’s engaged to a corrupt and wealthy politician (D.W. Moffett) runs off to Mexico in search of a sorceress after witnessing an apparent murder. Eventually she links up with a couple of guys (Russell Crowe and Jim Broadbent) who have separate reasons for being interested in her magic. Adapted by William Brookfield, former film critic Robert Mundy, and Peploe from James Hadley Chase’s novel Miss Shumway Waves a Wand, this visual treat recalls the whimsical postwar fantasies of Lewis Padgett (the pen name of writing team Henry Kuttner and C.L. Moore). The period flavor is witty and concise, the magic — which ultimately includes a talking dog and a man turning into a sausage — fetching and full of twists. (Fine Arts) — Jonathan Rosenbaum

Read more

Read more

This capsule review for the Chicago Reader is a way of mourning the untimely death of Berenice Reynaud, whose lovely book about the film offers a good sampling of her brilliant insights.

This remarkable and beautiful 160-minute family saga by the great Taiwanese filmmaker Hou Hsiao-hsien (Goodbye South, Goodbye, Flowers of Shanghai) begins in 1945, when Japan ended its 51-year colonial rule in Taiwan, and concludes in 1949, when mainland China became communist and Chiang Kai-shek’s government retreated to Taipei. Perceiving these historical upheavals through the varied lives of a single family, Hou again proves himself a master of long takes and complex framing, with a great talent for passionate (though elliptical and distanced) storytelling. Given the diverse languages and dialects spoken here (including the language of a deaf-mute, rendered in intertitles), this 1989 drama is largely a meditation on communication itself, and appropriately enough it was the first Taiwanese film to use direct sound. It’s also one of the supreme masterworks of the contemporary cinema and, as the first feature of Hou’s magisterial trilogy about Taiwan during the 20th century (followed in 1993 by The Puppetmaster and in 1995 by Good Men, Good Women), an excellent launch to the Film Center’s eight-film Hou retrospective, which runs over the next three weeks. Read more

From The Soho News (October 29, 1980). — J.R.

What attracted me to sign up in advance for a symposium called “Television/Society/Art,” put on at the Kitchen and NYU last weekend, was the opportunity to see and hear some old friends, encounter some new people, and maybe even get some new ideas (about what I should be reading and seeing, if nothing else): a bargain for the $10 registration fee.

Presented by the Kitchen and the American Film Institute and organized by Ron Clark, a senior instructor at the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program, the three-day event inevitably threatened a few dead spots — particularly to a virtual videophobe like me, who largely regards the medium as a kind of wicker basket holding a few magazines that I’m neither interested in reading nor quite ready to throw away. On the other hand, the fact that some of the invited panelists seemed to share the same bias made me suspect that I’d feel right at home.

The symposium got off to a somewhat inauspicious start with the presentation of a lumbering keynote paper entitled “Television Images, Codes and Messages” by Douglas Kellner, a teacher of philosophy at the University of Texas’s Austin campus. Read more

From the Chicago Reader (July 2, 2004). — J.R.

Before Sunset

**** (Masterpiece)

Directed by Richard Linklater

Written by Linklater, Kim Krizan, Julie Delpy, and Ethan Hawke

With Delpy and Hawke.

“The years shall run like rabbits,

For in my arms I hold

The Flower of the Ages,

And the first love of the world.”

But all the clocks in the city

Began to whirr and chime:

“O let not Time deceive you,

You cannot conquer Time….

“O plunge your hands in water,

Plunge them in up to the wrist;

Stare, stare in the basin

And wonder what you’ve missed.”

— from W.H. Auden’s “As I Walked Out One Evening” (1937)

Richard Linklater, like Wong Kar-wai on the opposite side of the globe, is a lyrical and elegiac filmmaker. In many of his films, as in many of Wong’s, the subject is time — the romance and poetry of moments ticking by, the wonder and anguish of living through and then remembering an hour or a day.

Future generations may look back at Linklater and Wong as poets laureate of the turn of the century who excelled at catching the tenor of their times. In Days of Being Wild and Slacker, Ashes of Time and The Newton Boys, Happy Together and Dazed and Confused, and In the Mood for Love and Before Sunrise they’re especially astute observers of where and who we are in history. Read more