Adapted from “Journal de Cannes,” translated by Jean-Luc Mengus, Trafic, no. 15, été [summer] 1995. — .J.R.

From 1970 to 1973, when I was living in Paris, it was still possible to write Cannes coverage for two magazines, stay in a cheap hotel, and not lose too much money, and last year I was able to start attending again thanks to being on the selection committee of the New York Film Festival. Despite the opening of a new Palais des Festivals in 1983 and the closing or remodeling of various cinemas, the most significant changes to be found here after two decades could arguably be summed up in a single phrase: what we mean when we say “contemporary cinema,” entailing not only what we include but what we leave out. In theory, all the beauty and horrors, the contradictions and paradoxes of world cinema are crammed in two weeks over a few city blocks. But in practice, how can we say with any confidence that Cannes is an accurate précis of anything except the international film business (which includes the press)?

Perhaps the biggest difference between the seventies and nineties in Cannes is the matter of whose opinions count the most. In the seventies, I, at least, had the illusion that it was those of the festival director, the programmers, or the jury. Today, it appears to be the opinions of Bob and Harvey Weinstein, the aggressive directors of Miramax — a company owned by Disney that seems to control a near-monopoly of important festival films, as producers, as distributors, or as both. Among their many past possessions are The Crying Game, The Piano, Pulp Fiction, Queen Margot (which they substantially recut), The Glass Shield (which they obliged Charles Burnett to write and shoot a new ending for before releasing), Ready-to-Wear (which they retitled from Prêt-à-porter, even after screening the film for the press), Krzysztof Kieslowski’s trilogy (Blue, White, and Red), and Priest (recut to placate the ratings board). They are the ones who most often determine which films will be altered (and how), when (or if) these films will open commercially, and how they will be advertised, exploited, and even written about, so “What do Bob and Harvey think?” is a question with vastly more ramifications than the opinions of, say, festival director Gilles Jacob or the head of this year’s jury, Jeanne Moreau.

In the early seventies, it was possible to see films here by Jean-Marie Straub and Danièle Huillet, Luc Moullet, Jean-Daniel Pollet, Edgardo Cozarinsky, Werner Schroeter, and the now mainly forgotten Carmelo Bene and Pedro Portabella, most often in the Director’s Fortnight or on the Market (though Bene’s One Hamlet Less actually turned up in the Palais in 1973.) Such options generally seem much less likely now. One of the key elements in this change is, of course, video and television — each realm a vast continent that siphons off much of what would formerly be considered “cinema.” The situation of Mark Rappaport in the United States is instructive: several years ago, he switched from 16-millimeter to video after funding for his features evaporated, but then he discovered that he couldn’t get his videos shown or reviewed unless they were transferred to film and then shown in that format at festivals.

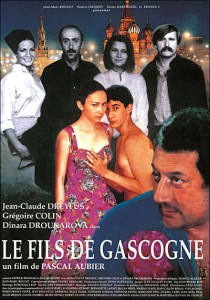

Certain haphazard rhyme effects between the seventies and nineties point up this problem in other ways. I still harbor fond memories of seeing Valparaiso . . .Valparaiso, Pascal Aubier’s satire about leftist myopia, at the Fortnight in 1973. But in order to see Aubier’s touching new comedy, The Son of Gascogne, at Cannes in 1995, it will be necessary to turn on a TV during one of the final evenings of this festival, which few critics here seem willing to do. Fortunately, I already saw this feature at the Berlin Film Festival’s Panorama in February, but for most of my colleagues, The Son of Gascogne will never be, even marginally, part of the French cinema of 1995 in the same way that Valparaiso . . . Valparaiso was part of the French cinema in 1973. This seems a pity, because if memories are to be trusted, the two films are complementary in significant respects: both are about elaborate hoaxes, and both are eloquent testimonies to some of the more cherished fantasy projections of their separate epochs.

In the more recent film, Aubier’s allegory about the myth of the Nouvelle Vague and the meaning of postmodernist pastiche seems a good deal more tender and forgiving than its predecessor, asking us to sympathize not only with the romanticism of an older generation but the frustrations of a younger one reduced to bluff and imitation in trying to live up to that heritage. It’s a good deal sadder as well, and in ways that seem directly relevant to Cannes — if only it were around as a reference point, as it once might have been. The same might be said for Cozarinsky’s Citizen Langlois, also seen in Berlin, a documentary that offers a polemical response to the nationalistic regulation of film history by state bureaucrats — a trend observable in most of the British Film Institute’s A Century of Cinema series at Cannes (aside from Godard’s 2 X 50 Years of French Cinema, which critiques the same project from within) — by justly treating Henri Langlois, the late cofounder and director of the Cinémathèque Française, as an antibureaucrat for whom cinema itself was the ultimate nationality.

But, judging from the other films shown in Cannes this year, including those in the market, personal essays — and indeed, most other kinds of nonfiction films, especially unconventional ones — are no longer part of “contemporary cinema.” (Could this help to explain why Françoise Romand’s extraordinary Mix-up, made ten years ago, is still so little known in France?) The commercial consensus appears to be that fiction films are universal and documentaries are parochial, with the result that the most universal testimonies that we have on certain subjects — Marker’s The Last Bolshevik, for example — get treated as marginal in Europe and the United States alike.

But, judging from the other films shown in Cannes this year, including those in the market, personal essays — and indeed, most other kinds of nonfiction films, especially unconventional ones — are no longer part of “contemporary cinema.” (Could this help to explain why Françoise Romand’s extraordinary Mix-up, made ten years ago, is still so little known in France?) The commercial consensus appears to be that fiction films are universal and documentaries are parochial, with the result that the most universal testimonies that we have on certain subjects — Marker’s The Last Bolshevik, for example — get treated as marginal in Europe and the United States alike.

Everywhere one looks, unconscious exclusions rule today’s film culture. Today, for instance, I purchased a copy of Gilbert Adair’s highly entertaining Flickers: An Illustrated Celebration of 100 Years of Cinema, just published by Faber and Faber — a personal selection of a hundred stills with accompanying commentaries, each representing a separate year—and read the following in Adair’s Introduction: “There are . . . of necessity, numerous, regrettable injustices: no L’Atalante, no Night of the Hunter, no Dovzhenko, Guitry, Wilder, Sirk, Mankiewicz, Kurosawa, Kiarostami or Nicholas Ray; no Garbo, Monroe or James Dean; no African or Latin American cinema at all.” It’s an intelligent list of exclusions, so it may seem carping to cite the absence of any of the Taiwanese or Hong Kong masters — Hou Hsiao-hsien, Edward Yang, Stanley Kwan, Wong Kar-wai — from Adair’s list of inclusions or his “injustices.” Indeed, over the past few years, whenever I hear friends tell me that the art of cinema is virtually over, Taiwan and Hong Kong never seem to figure as part of their reckoning.

May 22: The role played by publicity in informing, inflecting, and sometimes even replacing criticism is seldom acknowledged in print, yet our critical reading of many films would be radically different without its influence. A case in point is the construction of Larry Clark’s Kids as a “critical” site by Miramax over the first four months of 1995. Towards the end of the Sundance Festival in January, a special midnight screening was held of this cautionary, sensationalized, and very depressing first feature by an accomplished still photographer about casual teenage sex and AIDS in Manhattan, and the hyperbolic press responses that ensued seemed manufactured by Miramax’s sense of melodrama and its accurate gauging of American puritanism — both of which became, in effect, a critical reading of the film. Thus a Variety reviewer wrote (inaccurately) that the film offered no moral judgment of any kind on teenage sex, a Village Voice critic intimated that she had been in the presence of something great and innovative, and one of her younger West Coast colleagues excitedly wrote about “kiddie porn.”

Then, over the next several weeks, journalists speculated endlessly how Miramax, because of its affiliation with Disney, could possibly distribute the film. In short, just as one can speak about the smell of blood at the start of certain football games, the smell of money to be made now fosters an aura of “masterpiece” and “artistic breakthrough.” Much as Godard points out in 2 X 50 Years of French Cinema that centennial celebrations of “the cinema” are in fact only celebrations of the exploitation of cinema, the exploitation of Kids has so far been indistinguishable from its critical reception, even if the responses at Cannes have been mainly quite justifiable expressions of disappointment. The film isn’t bad, but the degree to which publicity has made it tower over every other American film at the festival can only distort its modest virtues and deceive its intended audience. (One American colleague who writes for a major newsweekly was instructed by his editor before the festival even started that Kids was the only film he could cover.)

Given the delirium of the press conference for Smoke at Berlin and the responses to Pulp Fiction at Cannes last year — both of them again Miramax films — a kind of carefully manufactured hysteria is clearly at work, and the degree to which journalists are projecting the focus of their articles and interviews for the following year, already anticipating the desires of their editors, determines the entire climate of such receptions. Any masterpiece failing to generate this kind of instant “copy” becomes by definition a bad film.