This film review appeared in The Soho News‘ November 12, 1980 issue. Agee (the writer) has long since then gone up again, considerably, in my estimation of his work. (Alas, the very pricey collection The Complete Film Criticism of James Agee, edited by Charles Maland, made it go down again.)

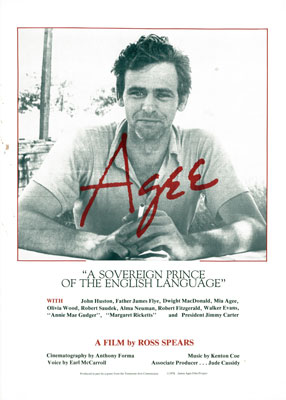

Ross Spears’ documentary about Agee, which was later nominated for an Oscar, can be ordered now on DVD, along with An Afternoon with Father Flye, from this site. —J.R.

Agee

A film by Ross Spears

Bleecker Street Cinema (The James Agee Room),

Nov. 14-16 and 21-23

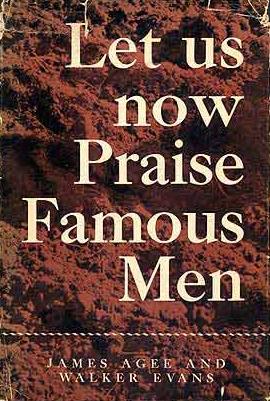

When I first saw this feature-length documentary (which is now officially inaugurating the Bleecker Street Cinema’s small, additional screening room) a year or so back, I was pleasantly surprised to find Jimmy Carter — on the campaign trail for the Presidency in ’76 –- making a guest appearance. In the opening moments of the film, he speaks with real intelligence and sensitivity about Let Us Now Praise Famous Men –- an angry, experimental, unclassifiable work of reportage, poetry and analysis about three Alabama tenant families near the height of the Depression, with photographs by Walker Evans and text by James Agee.

This wasn’t a bit like Richard Nixon declaring that he’d seen all of John Ford’s films, or Ronald Reagan leaking sincerity and integrity like a reptilian wallet in his old General Electric TV spots. It was the testimony of man who actually liked Agee’s outrageous, uneven, idiosyncratic book, comparing its style to that of Henry David Thoreau:

“I give the book to friends and tell them not to worry about the style when they read it, just to relax with it. I tell them it’s poetry,” Carter says warmly. Watching him say this a second time, on Election Day, at the beginning of Ross Spears’ slightly better-than-average (if conventional) literary bio-pic, I wondered if I was watching an ode to the defeat of guilty liberal humanism in more ways than one. Which is another way of saying that what seems interesting, troubling, and at the same time very ordinary about the legacy of James Agee applies in some ways to Carter, too.

As a scene-stealer, Carter actually takes a back seat to a handsome object that precedes him in closeup: a rare 1941 first edition of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men with a dust jacket -– an edition that originally sold fewer than 600 copies. Throughout the movie, the sheer physical presence of books, and poems and stories in their initial pristine magazine appearances, creates an arresting sort of literary erotics — peekaboo glimpses of print as sexy, in a way, as the burning, turning pages shown in Truffaut’s Fahrenheit 451.

Unfortunately, this sort of fleeting pleasure in Agee is often dovetailed into the tacky strategy of silently “staging” part of a text (e.g., The Morning Watch, A Death in the Family) with actors, while excerpts are monotonously read, with suffocating piety, offscreen. It’s a practice that Agee himself would surely have detested. And the fact that Spears does it “well” actually makes things worse, not better -– like Agee writing beautiful “appropriate” prose about Hiroshima for a Time cover story in 1945.

This brings me to the nub of my second thoughts about Agee (as well as Agee). If the correct and responsible way to deal with this movie is to start raving about Agee’s everlasting importance as a writer, I may be less than ideally suited to this task today. As someone who identified with the man excessively 20 years ago — perhaps because I was a Southern cigarette-smoking film freak and self-absorbed writer sequestered at a New England prep school — I can’t bring any fresh sense of discovery to his work. Like Fitzgerald and Hemingway and unlike Faulkner, his popular image as an artist conceivably has less to do with work produced than with a reputation for creative agony and carousing. It seems significant that his successes are mainly a matter of fragments and short distances, where he doesn’t have to worry as much about complex structures or overall dynamics.

***

The simple structure of Agee is basically built around interviews with the author’s friends and spouses. The latter, like his lifelong friend and teacher Father Flye, are accorded one chapter heading apiece in the film’s orderly procession of people and places: “Father Flye and Tennessee,” “Olivia, Harvard and New York,” “Alma and Alabama,” “Mia and the Movies”.

The friends — mainly Flye (who calls Agee “a sovereign prince of the English language”), poet Robert Fitzgerald, critic Dwight Macdonald, and director John Huston — are every bit as articulate as the wives, and fun to watch and listen to. It’s largely the relaxed, critical affection of these people that gives Agee a slight edge over the usual NET-style documentary.

Other artifacts and relics include Weegee footage of New York in the 40s, a Universal newsreel about the Hollywood Ten, and Agee’s brief appearance as a town drunk in The Bride Comes to Yellow Sky, which he scripted. (Regrettably missing are excerpts from In the Street and The Night of the Hunter, perhaps the two best films he collaborated on, although we do get a corny, characteristic clip — more drunk jokes, in fact — from The African Queen.)

Put this all together and what have we got? A pyrotechnical, passionate writer who, like the jazz pianists Art Tatum and Oscar Peterson, occasionally raises the question of whether pyrotechnics is always the best or most useful creative equipment to have. (One wife, Alma, speaks nicely about his agreeable lack of technique in playing tennis and piano.) One can continue to admire much of Let Us Now Praise Famous Men for the purity of its rage while realizing, at the same time, that the career of writing for Fortune, Time and Life that preceded, followed, and in many respects occasioned this rage — like the enormous quantities of alcohol, talk and tobacco associated with his legend — may have defined him as accurately in the long run.

This is also true of his film criticism for the Nation in the 40s — writing which is neither as avant-garde as Let Us Now Praise Famous Men nor as populist as Time but seeks, often brilliantly, to out-wisecrack other gifted malcontents. Unlike his younger friend and colleague Manny Farber, whose sharp conceptual eye could spot a major macho filmmaker — a Sam Fuller or Michael Snow –years before most people could imagine his existence, Agee was never much of a trailblazer in relation to movies. More precisely a performance artist in relation to writing, he could sing and dance about movies better than he could explain them.

At his best — on slapstick, Jean Vigo, Bogart/Hawks or fighting off the philistine hordes about Chaplin’s Monsieur Verdoux — Agee had a richly evocative prose, but seldom very much in the way of ideas (which made him, perhaps, the ideal Luce employee). Agee, as a film, hasn’t an idea in its head either. But as a middle-brow introduction to a writer whose baroque patches of pour-it-on prose and turgid swamps of liberal guilt inspired me for almost two decades (before I started overdosing and outgrowing it), it certainly delivers the goods.

—The Soho News, November 12, 1980