The reference-book entry was written in the mid-1970s for Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary (1980). (A much-expended version appeared in the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment.) And the review that comes after this was written for the Monthly Film Bulletin (May 1976, vol. 43, no. 508) — a publication of the British Film Institute, where I was serving at the time as assistant editor — and it follows most of the format of that magazine by following credits with first a one-paragraph synopsis and then a one-paragraph review. Mostly we covered features (all of those released in the country), but occasionally we also did shorts, such as this one. —J.R.

Tex Avery

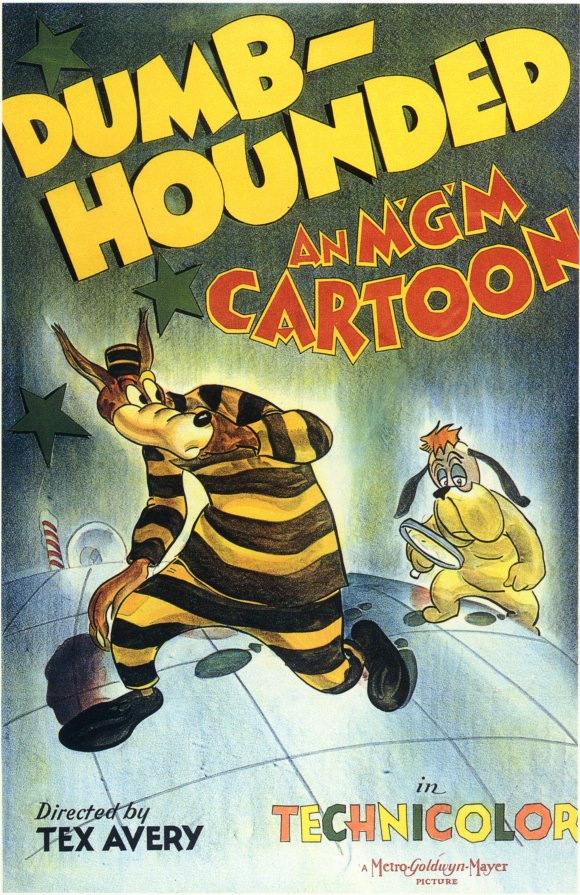

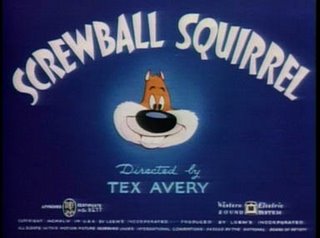

Tex Avery’s best cartoons seem to take off in one of two possible surrealist/narrative directions. A scattershot Hellzapoppin technique thrives on speed, multiplicity, surprise, incongruity, and paradox, with whatever plastic and thematic results ensue from this method. (Examples: Who Killed Who, 1943; Happy-Go-Nutty, 1944; Little Rural Riding Hood, 1949.) A more demonic-obsessive approach develops a single idée fixe to reductio ad absurdum proportions, maintaining roughly the same plastic and thematic concerns throughout. (Examples: Dumb Hounded, 1943; King Size Canary, 1947; Half-Pint Pygmy, 1948.)

With the aid of Heck Allen, Rich Hogan, and other collaborators, Avery provided indiscriminate audiences of the 40s and early 50s with neurotic miracles, bristling with energy and sophistication – and exclusively within seven or eight-minute formats. An Avery feature is inconceivable, and the difficulty of sitting through several of his shorts without suffering from repetitions of gags, structures, and tempi probably helps to explain some of their unjust neglect today. Clearly and splendidly works of their period, they invariably lose something when removed from their original context.

Among many pearls, one recalls the devastating Disney parody opening The Peachy Cobbler (1950), the ode to sadomasochistic schizophrenia comprising Droopy’s Double Trouble (1951), the elegant mixtures of animation and live-action (in Who Killed Who and Drag-a-long Droopy, 1954, among others), the bizarre treatment of objects as people in The Cat That Hated People (1948), and the elaborate cadenzas on sexual hysteria which proliferate throughout Avery’s work. Apart from his “textbook” importance as creator and developer of Bugs Bunny and Daffy Duck at Warners and Droopy at MGM (to cite only three instances) , one remembers Avery most for his perfectly rendered orchestrations of madness – which ironically appear, next to the idealism of Disney, like doses of good common sense.

–written for Cinema: A Critical Dictionary – The Major Filmmakers, vol. 1, edited by Richard Roud, New York: The Viking Press, 1980; slightly revised, 2009

Little Rural Riding Hood

U.S.A., 1949

Director: Tex Avery

Cert—U. dist—Ron Harris. p.c—MGM. p—Fred Quimby. story—Rich Hogan, Jack Cosgriff. col—[originally made in Technicolor], anim—Grant Simmons, Walter Clinton, Bob Cannon, Michael Lah. m—Scott Bradley. song—“Oh, Wolfie”. 228 ft. 6 min. (16 mm.).

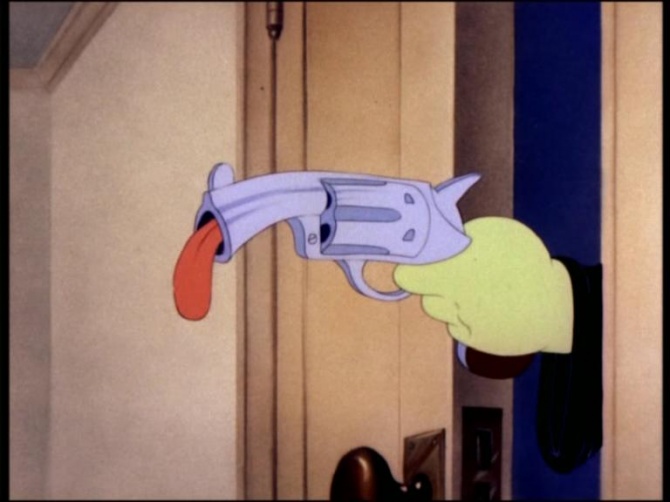

A rural Red Riding Hood explains to the audience that she’s on her way to her grandmother’s house; a disguised rural wolf awaits her in bed, explaining that his desires are purely carnal. After an elaborate chase, a telegram arrives from the wolf’s city cousin inviting him to visit and meet a ‘real’ woman, with a photo enclosed. The country wolf rushes excitedly to his urbane cousin’s flat, where they don tuxedoes and head for a nightclub. There an urban Red Riding Hood performs a song that drives the country wolf into convulsions of sexual hysteria, until his soft-spoken cousin, embarrassed by the spectacle, drags him away and drives him back to the country – where he himself goes equally mad over the rural Red Riding Hood.

If the comedy of Tex Avery is generally ruled by polar extremes –- fast and slow, big and small, loud and quiet, crazy and cool -– there are few manifestations of sheer dialectical extravagance more pronounced than Little Rural Riding Hood. The schematic plot provides only the barest hint of the exaggerations in store: while the country heroine is as ugly and skinny as a rotting flagpole, her city counterpart is about as curvaceous as the late Forties censors would permit, and next to the soft-spoken poise and demeanor of the urban wolf – as languorous as a Don Ameche 78 played at 16 r.p.m. – his rural cousin is an exploding combustion engine filled with Roman candles and cherry bombs who, from the very start, wants to catch the rural Riding Hood so that he can “chase her and catch her and kiss her and hug her…” The grand climax of Avery’s manic sex cycle at MGM, which began with Red Hot Riding Hood in 1943 and continued through The Shooting of Dan McGoo, Swingshift Cinderella, and Wild and Woolfy (1945), Uncle Tom’s Cabaña (1947), and Little ‘Tinker (1948), this anthology of erotic longings, physical contortions, and surrealist outrages –- all dealt out in swift overlapping succession -– shows the Avery manner at its most exhaustive as well as its most exhausting, depending on quantity as much as quality for its effects. The initial chase of wolf after girl offers an instant encyclopedia of slamming, multiplying, and dismembering doors; the city cousin’s limousine seems as long as the Lincoln Tunnel; and the country wolf’s frustrated attempts to whistle at the nightclub comprise an inventory of shorthand nightmares about irresistible forces and immovable objects. Such procedures propose overstatement as the basic comic unit throughout -– a tradition suggesting not only the tall tale in general, but Avery’s Texas background in particular.

—Mont{hly Film Bulletin, May 1976, vol. 43, no. 508