I’m pretty sure that this was the first submitted draft of my commissioned Op Ed piece for the New York Times, written in late July, 2007. It comes far closer to what I felt at the time than the version that emerged after three separate rewrites were requested by my editor, Mark Lotto, which was published on August 4, and which I hadn’t much desire to reprint until mid-October 2018, when I decided to attach the printed version as an afterthought. Typically, the title that was run with the piece, “Scenes from an Overrated Career,” wasn’t mine, yet paradoxically (if understandably) this was what many readers seemed to find most objectionable.

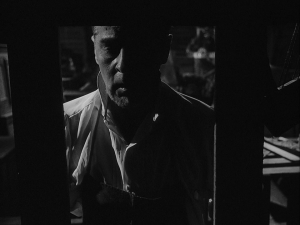

I’m sorry that I haven’t been able to illustrate the attic scene that I describe in The Magician, so I’ve substituted a still from Sawdust and Tinsel at the head of this piece that suggests some spatial disorientation. [2015 postscript: a generous reader, Dan Roy, has helped me out with the attic scene.] –- J.R.

If memory serves, my first taste of Ingmar Bergman was The Magician, seen at the 5th Avenue Cinema in the spring of 1960, en route from a New England boarding school to my home in Alabama during spring break. The key moment for me in this 19th century tale was when the title hero — the mute Vogler (Max von Sydow), one of Bergman’s many ironic self-portraits of the artist as resentful outsider — takes revenge on a skeptical patron by submitting him to a series of harsh spatial confusions in an attic. I became so confused by these visual displacements myself that I staggered out of the auditorium with the distinct impression that the 5th Avenue Cinema was located south of Washington Square, not north.

That’s a fictitious location that still seems real to me, where a part of me still can be said to reside. The same can be claimed for the indelible landscapes of Bergman’s cinema, composed mainly of faces and shallow interiors, which have haunted filmgoers across the globe. For French critics like Jean-Luc Godard during the previous decade, discovering Bergman through films like Summer Interlude (1951) and Summer with Monika (1953) meant encountering Maj-Britt Nilsson and Harriet Andersson, among other actresses, as well as Bergman’s own acute appreciation of their sensuality. For younger cinephiles like myself, discovering Bergman around the same time I was discovering Godard and Alain Resnais, it was tempting to view his beautifully shot and acted chamber works as similarly new and unprecedented. The stylistic departures that opened Sawdust and Tinsel (1953) and, much later, Persona (1966), two of his best films, like the self-consciousness of the trickery in The Magician, may have suggested a modernist sensibility, but these ruses proved to be functions of Bergman’s theatrical skill more than reflections of the contemporary world.

Unlike Michelangelo Antonioni, who died on the same day, Bergman wasn’t really a 20th century artist, even though that was when he made all but the last of his features. Only years after I discovered his work, when I learned to love the more substantial films of Carl Dreyer —- another Swede, albeit one raised as a Dane — did I start to understand that the tradition embodied by Bergman was mainly rooted in the late 19th century, like the theater of Strindberg and Ibsen that he was repeatedly drawn to. Significantly, his stage repertory was traditional — only the films had original scripts —- and based on the testimony of some friends lucky enough to have seen some of Bergman’s stage productions when they traveled in their untranslated Swedish to Brooklyn, I think there’s strong reason to believe that the theater was his real métier. According to www.ingmarbergman.se, there were “170 productions for stage, television and radio between 1938 and 2004,” and “fifty or so films for cinema and television” between 1946 and 2003 —- an awesome output in both realms. Nevertheless, a proper account and estimation of his theater work is long overdue.

Dreyer would reinvent film language in each of his features, but Bergman simply used film (and later video) to translate or transfer the shadow-plays in his mind, most of which could be traced back to the Lutheran repression and spiritual desolation of a previous era. One of the most striking aspects of the use of digital video in Saraband (2003), his last feature, is his seeming contempt for the medium apart from its usefulness as a recording device, mainly as a way of capturing his work with actors. Even in his consummate employment of Sven Nykvist’s cinematography over three decades —- which for me lost something after he abandoned black and white at the end of the 60s — what mattered most were the actors in front of the camera, the members of Bergman’s troupe, not the language the films spoke. Like John Ford, one of his own favorites, he could recast the world again and again through his team of players.

Scenes from an Overrated Career

Jonathan Rosenbaum

Chicago

THE first Ingmar Bergman movie I ever saw was “The Magician,” at the Fifth Avenue Cinema in the spring of 1960, when I was 17. The only way I could watch the film this week after the Swedish director’s death was on a remaindered DVD I bought in Paris. Like many of his films, “The Magician” hasn’t been widely available here for ages.

Nearly all the obituaries I’ve read take for granted Mr. Bergman’s stature as one of the uncontestable major figures in cinema — for his serious themes (the loss of religious faith and the waning of relationships), for his expert direction of actors (many of whom, like Max von Sydow and Liv Ullmann, he introduced and made famous) and for the hard severity of his images. If you Google “Ingmar Bergman” and “great,” you get almost six million hits.

Sometimes, though, the best indication of an artist’s continuing vitality is simply what of his work remains visible and is still talked about. The hard fact is, Mr. Bergman isn’t being taught in film courses or debated by film buffs with the same intensity as Alfred Hitchcock, Orson Welles and Jean-Luc Godard. His works are seen less often in retrospectives and on DVD than those of Carl Dreyer and Robert Bresson — two master filmmakers widely scorned as boring and pretentious during Mr. Bergman’s heyday.

What Mr. Bergman had that those two masters lacked was the power to entertain — which often meant a reluctance to challenge conventional film-going habits, as Dreyer did when constructing his peculiar form of movie space and Bresson did when constructing his peculiar form of movie acting.

The same qualities that made Mr. Bergman’s films go down more easily than theirs — his fluid storytelling and deftness in handling actresses, comparable to the skills of a Hollywood professional like George Cukor — also make them feel less important today, because they have fewer secrets to impart. What we see is what we get, and what we hear, however well written or dramatic, are things we’re likely to have heard elsewhere.

So where did the outsized reputation of Mr. Bergman come from? At least part of his initial appeal in the ’50s seems tied to the sexiness of his actresses and the more relaxed attitudes about nudity in Sweden; discovering the handsome look of a Bergman film also clearly meant encountering the beauty of Maj-Britt Nilsson and Harriet Andersson. And for younger cinephiles like myself, watching Mr. Bergman’s films at the same time I was first encountering directors like Mr. Godard and Alain Resnais, it was tempting to regard him as a kindred spirit, the vanguard of a Swedish New Wave.

It was a seductive error, but an error nevertheless. The stylistic departures I saw in Mr. Bergman’s ’50s and ’60s features — the silent-movie pastiche in “Sawdust and Tinsel,” the punitive use of magic against a doctor-villain in “The Magician,” the aggressive avant-garde prologue of “Persona” — were actually more functions of his skill and experience as a theater director than a desire or capacity to change the language of cinema in order to say something new. If the French New Wave addressed a new contemporary world, Mr. Bergman’s talent was mainly devoted to preserving and perpetuating an old one.

Curiously, theater is what claimed most of Mr. Bergman’s genius, but cinema is what claimed most of his reputation. He was drawn again and again to the 19th-century theater of Chekhov, Strindberg and Ibsen — these were his real roots — and based on the testimony of friends who saw some of his stage productions when they traveled to Brooklyn, there’s good reason to believe a comprehensive account of his prodigious theater work, his métier, is long overdue.

We remember the late Michelangelo Antonioni for his mysteriously vacant pockets of time, Andrei Tarkovsky for his elaborately choreographed long takes and Orson Welles for his canted angles and staccato editing. And we remember all three for their deep, multifaceted investments in the modern world — the same world Mr. Bergman seemed perpetually in retreat from.

Mr. Bergman simply used film (and later, video) to translate shadow-plays staged in his mind — relatively private psychodramas about his own relationships with his cast members, and metaphysical speculations that at best condensed the thoughts of a few philosophers rather than expanded them. Riddled with wounds inflicted by Mr. Bergman’s strict Lutheran upbringing and diverse spiritual doubts, these films are at times too self-absorbed to say much about the larger world, limiting the relevance that his champions often claim for them.

Above all, his movies aren’t so much filmic expressions as expressions on film. One of the most striking aspects of the use of digital video in “Saraband,” his last feature, is his seeming contempt for the medium apart from its usefulness as a simple recording device.

Yet what Mr. Bergman was interested in recording was pretty much the same tormented and tortured neurotic resentments, the same spite and even the same cruelty that can be traced back to his work of a half-century ago. Like John Ford, one of Mr. Bergman’s favorite directors — whose taste for silhouettes moving across horizons he shared — he would endlessly reshuffle his reliable troupe of players, his favorite sores and obsessions, like shards of glass in a kaleidoscope.

It’s strange to realize that his bitter and pinched emotions, once they were combined with excellent cinematography and superb acting, could become chic — and revered as emblems of higher purposes in cinema. But these emotions remain ugly ones, no matter how stylishly they might be served up.

Even stranger to me was the way he always resonated with New York audiences. The antiseptic, upscale look of Mr. Bergman’s interiors and his mainly blond, blue-eyed cast members became a brand to be adopted and emulated. (His artfully presented traumas became so respectable they could help to sell espresso in the lobby of the Fifth Avenue Cinema.) Mr. Bergman, famously, not only helped fuel the art-house aspirations of Woody Allen but Mr. Allen’s class aspirations as well — the dual yearnings ultimately becoming so intertwined that they seemed identical.

Despite all the compulsive superlatives offered up this week, Mr. Bergman’s star has faded, maybe because we’ve all grown up a little, as filmgoers and as socially aware adults. It doesn’t diminish his masterful use of extended close-ups or his distinctively theatrical, seemingly homemade cinema to suggest that movies can offer something more complex and challenging. And while Mr. Bergman’s films may have lost much of their pertinence, they will always remain landmarks in the history of taste.