This essay was written between 1999 and 2001 for Movie Mutations: The Changing Face of World Cinephilia, a 2003 collection I coedited with Adrian Martin and wrote (or, more often, cowrote) many pieces for. This particular piece was part of a section of the book entitled “Two Auteurs: Masumura and Hawks” that I collaborated on with the great Japanese film critic Shigehiko Hasumi, which also included two dialogues with him and a lengthy essay by him about Howard Hawks. — J.R.

To appropriate one of the categories of Andrew Sarris’ The American Cinema, Yasuzo Masumura (1924-1986) is a “subject for further research”. My first encounter with his work was almost thirty years ago in Paris, where his Love For an Idiot (Chijin no ai, 1967), an updated adaptation of Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1924 novel Naomi, was playing under the title La chatte japonaise. (As I would discover much later, there are two other excellent Tanizaki adaptations in his oeuvre -– Manji [Swastika, 1964] and Tattoo [Irezumi, 1966].) Spurred by a twelve page spread in the October 1970 issue of Cahiers du cinéma –- perhaps the most extensive critical recognition he’s received to date in the West -– I found myself both shocked and intrigued by this depiction of the erotic delirium of a middle-aged factory worker over the much younger wife he trains, marries and loses. Read more

The reference-book entry was written in the mid-1970s for Richard Roud’s Cinema: A Critical Dictionary (1980). (A much-expended version appeared in the January-February 1975 issue of Film Comment.) And the review that comes after this was written for the Monthly Film Bulletin (May 1976, vol. 43, no. 508) — a publication of the British Film Institute, where I was serving at the time as assistant editor — and it follows most of the format of that magazine by following credits with first a one-paragraph synopsis and then a one-paragraph review. Mostly we covered features (all of those released in the country), but occasionally we also did shorts, such as this one. —J.R.

Tex Avery

Tex Avery’s best cartoons seem to take off in one of two possible surrealist/narrative directions. A scattershot Hellzapoppin technique thrives on speed, multiplicity, surprise, incongruity, and paradox, with whatever plastic and thematic results ensue from this method. (Examples: Who Killed Who, 1943; Happy-Go-Nutty, 1944; Little Rural Riding Hood, 1949.) A more demonic-obsessive approach develops a single idée fixe to reductio ad absurdum proportions, maintaining roughly the same plastic and thematic concerns throughout. (Examples: Dumb Hounded, 1943; King Size Canary, 1947; Half-Pint Pygmy, 1948.) Read more

Posted in Moving Image Source on November 13, 2009. — J.R.

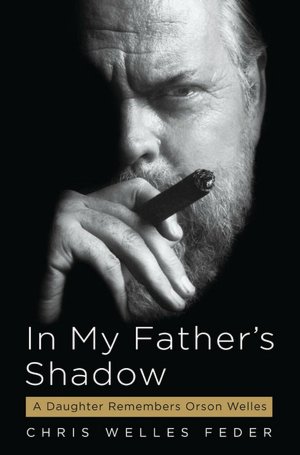

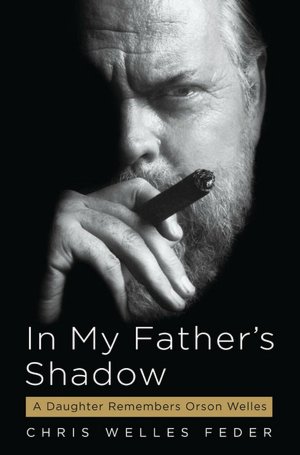

“The book you are about to read is not another biography of Orson Welles,” begins Chris Welles Feder’s In My Father’s Shadow: A Daughter Remembers Orson Welles (Algonquin Books of Chapel Hill). “It owes nothing to scholarly research and everything to firsthand knowledge.” Because this story by Welles’s oldest daughter is about neglect and absence as well as about love and presence, one feels from the outset that her very moving cri de coeur was written out of psychic necessity rather than out of any academic or commercial impulse — a passionate and even somewhat desperate attempt to lay certain ghosts to rest. And part of this book’s uncommon strength is that it ends on a positive note with a lot of hard-won wisdom, in spite of all the grief it recounts.

Orson Welles married three times and had a daughter from each marriage, although the woman who mattered the most in his life, at least during the last two decades, was none of these half-dozen women but Oja Kodar, his mistress and collaborator (mainly as actress and/or co-writer — on F for Fake, the unreleased The Other Side of the Wind, and many other unfinished or unrealized projects, such as The Dreamers). Read more