This critical memoir originally appeared in the Spring 1983 Sight and Sound; it was subsequently reprinted in my first collection (1995), Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism. — J.R.

It was about ten years ago, in late November 1972, that I first took the No. 163 bus from Porte de Champerret in Paris to Jacques Tati’s office in la Garenne-Colombes, just around the corner from an unassuming street known as Rue de Plaisance. With his assistant Marie-France Siegler — a French- American in her thirties who, like me, hailed from Alabama, and had set up this interview — Tati occupied two offices in a modern building whose suburban neighborhood bore visible traces of both the contrasting quartiers in MON ONCLE: the chummy old lower-middle-to-working-class district where an unemployed Hulot lives, and the sterile, newly built upper-to-middle-class subdivision where his “successful” brother lives.

The modern building, fronted by a glass door with a disc-shaped brass knob, was no less suggestive of PLAYTIME, and Tati’s office contained other familiar emblems, such as the same synthetic black chairs. In fact, around the period of MON ONCLE (1958), his production company had commanded the entire floor; he had restricted himself to two modest rooms only after investing and then losing practically everything he had on PLAYTIME (1967), his most expensive film, the masterpiece that wrecked his career. And the previous year, 1971, he had released TRAFlC, an attempt to salvage his career. He was sixty-four when I first met him, although he hadn’t made his first film as a director until he was practically forty.

It was easy enough to be liked by Tati. All one had to do was say that PLAYTIME was one’s favorite film (which was true), that it had actually changed one’s way of looking at people and things in cities (also true), and after almost two hours of pleasant interview in English — most of it later published in the May-June 1973 Film Comment — he was half-seriously assuring me that if I ever needed a place to stay, I could sleep in his office. (My hair was longer in those days; that and my lack of fluency in French may have led him to assume that I might not have had a place of my own in Paris.) At the same time, it was possible to see more than one side of his mood that afternoon: an hour later, while having a drink with Marie-France in the bistro on the ground floor of the same building, I saw her boss angrily stride in, beet-red, and chasten her in French for not being around when she was needed. He was not an easy man, nor was he having an easy time of it.

Becoming friendly with Marie-France through our shared Alabama backgrounds, approximate ages, and enthusiasm for Tati, I wound up writing an English commentary for a 16-millimeter short she had made called LA DERNIERE NUIT DES HALLES. (A onetime mime student whose life had been profoundly affected by MON ONCLE, as much through her identification with its social protest as through her fascination with its technique, she shared with Tati a notion of the simple and everyday as a continuous circus, and her tender

and sentimental farewell to Paris’s fruit and vegetable market was really a film about the circus closing down.) After that we had stayed sporadically in touch, and in early January she called me with the mind- boggling news that Tati was interested in working with me on the script of his next film, a project about television called CONFUSION. And for much of the remainder of that month, on an almost daily basis, I was going out to la Garenne-Colombes to do precisely that.

I was flattered, even awed, but also rather bewildered: apart from my sympathy as a critic and interviewer, what possible use did Tati have for an American writer* — a use, moreover, for which he was willing to pay me? As I had discovered in our interview, he was a completely nonverbal sort; a man whose mime-like habits made his body language and vocal sound effects closer to the sound of his “voice” than actual speech. He thought with his body, and it wasn’t at all clear to me how I could contribute meaningfully to that process.

Understanding was gradual, and came only from the actual practice of our afternoons together. In a way, E. M. Forster’s “How do I know what I mean until I see what I say?” could be translated into the question repeatedly posed by Tati’s body language, which was central to his method — namely, “How do I know what I think until I see what I do?” And in order to see what he did, he needed a spectator, another set of eyes and ears, someone to respond to his gags and improvisations. It’s a method many comics follow; where I suspect it differed most for Tati was in his compulsion to reproduce in his body as much of the image and sound as

was humanly possible, playing aIl the characters and props that figured in the action.

A cInematic raconteur, Tali possessed a talent for evoking the formal impact of a shot with his voice and body which is shared, to my knowledge, only by Kevin Brownlow and Sam Fuller — two other wild men quite capable of leaping about and squawking, if necessary, to Illustrate what a particular moment of film might be like. For Brownlow, it is a favorite film moment remembered and savored (most often through vocal inflections; for Fuller, it is a crazed conceptual notion that his pulp imagination and cheap energy turn into some variant of Godardian aggression. But for Tati — taller, more legato and lopIng In demeanor– it was always a gesture that came from life, not art. Neither a cinéphile nor (by and large) a director for cinéphiles, Tati lacked the polemical stance regarding the rest of cinema that characterizes Bresson, although he had a similar dislike for professional actors. (In defense of the costly sets of PLAYTIME, he would argue, “They’re not more expensive than Sophia Loren.”)

He wasn’t an intellectual or someone who read much — although, among film critics, he was unstinting in his praise for Bazin and Sadoul. During one of our first sessions, while I was still trying to figure out why he had hired me, I ventured that, because the principal subject of CONFUSION was television, it might perhaps be worth thinking some about, say, Marshall McLuhan. The suggestion brought blank stares from Tati as well as from Marie-France. After a brief explanation of McLuhan’s reputation and influence in the States at the time — so pronounced, I recall, that during my grad school days in the mid-1960s, there was an undergraduate course in existentialism at the State University of New York at Stony Brook which used Understanding Media as its sole textbook — it quickly became clear that they weren’t interested in the

slightest.

No less doomed was any extended effort to discuss other people’s films. The current favorite of Tati and Marie-France when I was working for them was HAROLD AND MAUDE. At various times, he expressed admiration for Keaton and Kubrick (as well as for Woody Allen’s BANANAS), but never went into any detail. When I suggested at one point that he see Buñuel’s LE CHARME DISCRET DE LA BOURGEOISIE, he could only muse about who this Buñuel fellow was. Wasn’t he the chap who made a film — he forgot the title — strongly influenced by his JOUR DE FÊTE?

The way our work proceeded always depended on his moods, and each afternoon was different. After the first week or so, I was lent a copy of the treatment he had already prepared in French for CONFUSION, chiefly a description of various situations and gags involving Hulot set either in a television studio or out on various news sites and/or shooting locations. Much of this was satire about the phony clamor of American television (the bilingual title was as deliberate as the franglais of PLAYTIME and TRAFIC), which Tati had already spoken about in our interview. “When you see people on American television, the way they speak and move and wear their clothes (they all have wigs, you can see them) — nothing is real. That’s why what they create isn’t warm, or natural. When you see all that cream they put in the commercials — I watched from 9 A.M. to 11 :30 and I saw only cream, everywhere: cream on the bread, cream on the shoes, cream on the face, cream on the potatoes, cream to be dirty — chocolate cream, that looks like I don’t know what. At 12:30 I had

an opportunity for lunch and I said, ‘Really, I’m not joking, I can’t eat.'”

For a while, I used to fantasize ways that Tati could extend his multiple focal points through his uses of television — such as Hulot repeated countless times on various television sets in a window, or monitors in a studio. But mainly it was a matter of talking, looking, and listening. Some days, when what he called his Slavic side predominated (he had a Russian father called Tatischeff), a cloud of melancholia would seem to descend over him, and it would become hard to work. Sometimes he would take down his large scrapbooks

devoted to the production of PLAYTIME and linger over photographs of the sets.

***

Tati always trusted children more than adults. Animals could elicit a lot of attention and respect, too: I recall him performing for somebody’s dog in a restaurant for a good ten minutes, evidently more concerned with the dog’s responses to his antics than with those of any human onlookers. One time he recounted screening PLAYTIME privately for a small group of film industry bigshots, one of whom had to bring along his little girl because he couldn’t get a babysitter, a fact for which he apologized profusely. Then, after the film started, she did something truly unforgivable: every time there was a gag, she would giggle, causing her nervous father to turn around and shush her. It was a story recounted, of course, by Tati playing alternately the little girl and her father, oscillating between delight and horror with a regularity suggesting ping pong.

“The birth of the reader must be ransomed by the death of the author,” Roland Barthes wrote in the 196Os. “I think PLAYTIME is revolutionary in spite of Tati,” Jacques Rivette said during the same decade. “The film completely overshadowed the creator.” ”PLAYTIME is nobody,” Tati more instinctively said to me during our interview. Yet, as it became increasingly clear to me, the birth of Tati the director had to be ransomed by the death of Hulot the performer. It was an existential crisis of the first order, and his career never quite recovered from it. People who never heard of Tati loved Hulot, whereas Tati personally was sick and tired of Hulot, a character originally invented for only one film, and which the public refused to let him abandon, rather as Conan Doyle’s reading public refused to let him dispose of Sherlock Holmes. Hulot remained Tati’s bread and butter, but it was this same lunar presence who stood between him and his desire to be a director. Not like Chaplin, who merely regarded direction as the placement of his performance, but quite the reverse: a vIsion that democratized the holy fool so that he/she occupied every comer of the frame, every character and object and sound no longer the emperor of a privileged space.

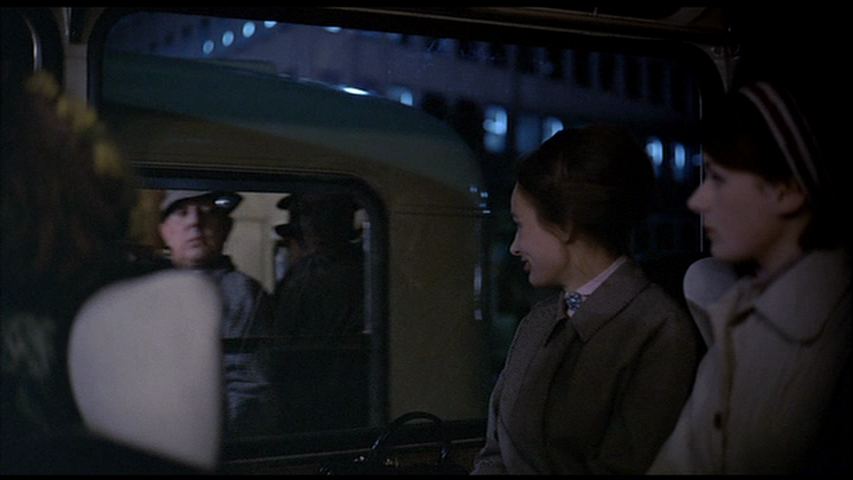

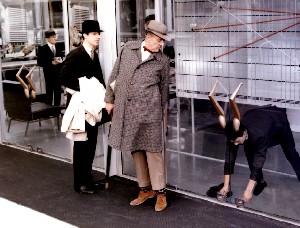

Hulot as star got in the way of all that. This was true even in LES VACANCES DE MONSIEUR HULOT, where Tati discovered that he could evoke Hulot without his actual presence; the rattle and sputter of his off-screen car sufficed. It is equally the point of all the false Hulots in PLAYTIME, who form a sort of chain of being between Hulot himself and all the nondescript bumblers in the audience. One lookalike drops his umbrella in the background of a shot at Orly, distracting us from the arriving party of female American tourists; another behaves at a gadget exhibit in a boorish manner that gets the real Hulot in trouble; a third presents a going-away gift from Hulot to Barbara, the film’s heroine, which Hulot can’t deliver himself. The absolute equivalence of real and false Hulots is basic to the film’s ethics and aesthetics, which deplore the kinds of space created by stars, whether human or architectural.

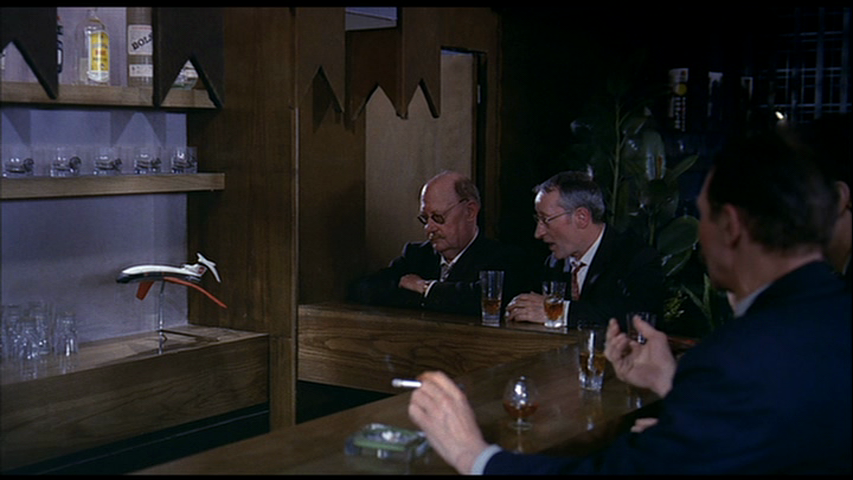

It was a singular experience to accompany Tati to the bistro downstairs for lunch — a recognizable miniature version of the Royal Garden Restaurant in PLAYTIME. His behavior there would seesaw almost dialectically between observation and clowning: the way another customer moved would amuse or delight him and he would duplicate the gesture immediately, with a manic glee that was unnerving if you happened to be the one he was copying. One afternoon, arriving for work, I checked the restaurant for Tati and Marie-France, went upstairs and found the office doors locked, and then returned to the restaurant only to discover that a few feet from my very nose, near the entrance, sat the two of them at a table, hugely diverted by my bemusement, waiting for me to discover them. Becoming part of a Tati gag was inevitable if you hung around him, but it always became part of a dialectic when the copied version was transmitted back to you. It was the same way, I’m told, that he directed performances in his films: imitate the funny way that someone walked, then ask him or her to imitate his imitation.

The physicality of Tati’s comedy is intimately involved with the love and hatred it can elicit from spectators, in part according to the ways that they relate to their own physicality and that of their immediate environments. The world he depicts is a peculiar one consisting of public events viewed from private perspectives (a touching example from JOUR DE FÊTE: the village postman’s horrified look at discovering via a newsreel how mail is delivered in America), a central theme of modernism that actually places Tati in the unexpected company of Joyce and Eisenstein (as well as Duras, Godard, Rivette, and Straub-Huillet, among closer contemporaries who revere his work), so that in the second half of PLAYTIME, Tati could achieve through intuitive genius a network of polyphonic complexities such as Eisenstein and the others arrived at mainly by conscious design.

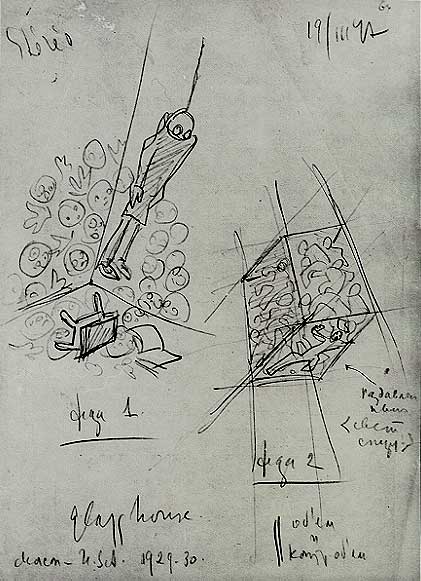

If this connection sounds farfetched, think of the intricate trajectories of diverse characters and objects through a single day and city in Ulysees and PLAYTIME, or the striking anticipation of the latter in THE GLASS HOUSE — a favorite unrealized project of Eisenstein’s described in some detail in Jay Leyda and Zina Voynow’s recent and very beautiful Eisenstein at Work (Pantheon Books/The Museum of Modern Art, 1982). As Ted Perry usefully summarizes in his introduction:

One of the cIearest examples of. how poIyphony could serve as the generative idea for an entire film occurs in the notes and sketches which Eisenstein made for a never-realized enterprise entitled THE GLASS HOUSE. The undertaking drew its inspiration from a number of different sources: the visit to the new glass wonder that was the Berlin Hessler Hotel, some knowledge of Zaymaytin’s novel entitled We, and Frank Lloyd Wright’s plans for a glass skyscraper. As early as 1926 and as late as 1947 Eisenstein made notes and sketches for the project. He was fascinated with the visual possibilities of seeing multiple actions in different parts of a glass house where opaque objects, such as rugs, would interrupt the line of sight and serve as compositional devices. Of utmost interest was the possibility that the same shot, or scene, could contain not only an action but also people, on the other side of the glass walls, seeing and reacting to the action. Eisenstein’s term for such a film, stereoscopic, referred not only to the three-dimensional quality of the image but also, and more importantly, to the simultaneous interplay of the subjective and the objective. Instead of a shot of an event alternating with a shot of people’s reaction, the objective event and the subjective reaction would take place within the same image.

No wonder Eisenstein could write on February 15, 1928, “On Saturday received Ulysees, the Bible of the new cinema” […]

***

The American release of PLAYTIME, six years after its completion, occurred around the time I was working for him, when he had no control over the shortened 35-miIIimeter version being shown. By then, he also had no control over (or revenues from) the widespread distribution of many of his films in 16-millimeter in the United States. Apart from knowing that he was bankrupt and that pirated dupes of PLAYTIME seemed to be proliferating everywhere, I never had any clear sense of all his s financial difficulties. The last time I saw him on a brief visit to Pans from London in February 1977, he was about to leave for Switzerland to show the original 70- millimeter, 151-minute version of PLAYTIME, which I’ve never seen; he invited me to come along, but my schedule made it impossible. He still owned the only complete 70-milIimeter version, but I later heard, rightly or wrongly, that he had had to give that up too when the rights to all his films were auctloned off.

I don’t know if he ever understood what hit him; I’m not at at sure that I do, either. Our meetings were discontinued when he became ill, and before our last meeting in 1977, I can recall seeing him again only when he showed PARADE at the London Film Festival in December 1975. A year earlier, at a Paris Left Bank cinema, during my first look at PARADE, I found myself, to my embarrassment, weeping uncontrollably. It was a circus show he had videotaped in Sweden and transferred to film. A friend at the time who despised Tati had told me it was pathetic, and I felt that it was almost like what seeing Griffith’s THE STRUGGLE must have been like in 1931 — beautiful for what it was, yet excruciating in relation to what one knew its director wanted to do and was capable of doing.

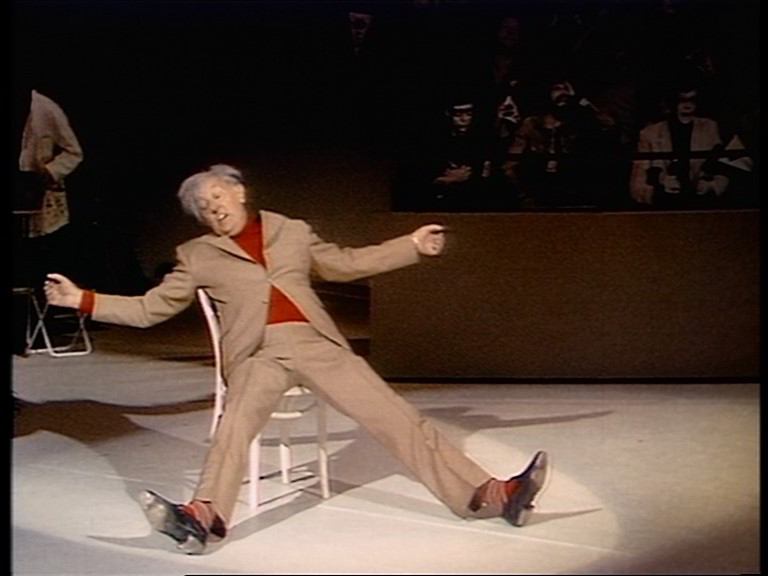

In retrospect, though, it has grown in importance for me. It has none of the bitterness that intennittently mars TRAFIC (a more compromised work in its inception, because its commercial viability required the star presence of Hulot), and equates spectator and performer more decisively. One can also appreciate the relief with which Tati finally abandons his nemesis here, returning to the pantomimes that initially launched him in the music halls, about which Colette marveled, “He has created at the same time the player, the ball,

and the racket; the boxer and his opponent; the bicycle and its rider. His powers of suggestion are those of a great artist.”

By the time I saw PARADE again in London, this much was clear to me; it remains to be seen for most other people, who eight years later have still never heard of the film. I remember telling Marie-France how much I liked PARADE, and the unbridled pleasure that broke out on Tati’s face when she reported this to him a few moments later. His bad health was more visible by then, but he was big and powerful for a Frenchman, and he hung on for seven years more. From time to time, one would hear rumors in the press about CONFUSION being reanimated as a project, but the financing never came together. He clearly had reached the end.

Yet the true death of Hulot, as far as I’m concerned, occurred not in late 1982, when Tati died, but in early 1973, at the most fruitful of all our afternoon sessions. If memory serves, it was also the last. Tati was musing about how he’d like to start off CONFUSION with something truly outrageous: have the screen grow dark, for instance, so that kids in the audience would start whistling (he promptly imitated them); make it look as though the film broke or caught fire or…or what about killing off Hulot, once and for all? Suddenly Tati got up from his desk — he always thought best on his feet — and started pacing about his little cubicle, blocking out a scene. Yes, they would be transmitting something like a live soap opera or melodrama from a television studio, and real bullets would accidentally be inserted in a prop gun instead of blanks. Hulot would be a studio technician; or, even better, an innocent bystander who was there for some other reason and stopped to watch this live perfonnance, and when one hammy actor pulls out his pistol to blast another hammy actor, he misses and instead shoots dead an out-of-frame Hulot.

Consternation in the studio; they can’t stop the action because this is live, the show must go on. So the melodrama continues while the crew frantically conspires to remove Hulot’s corpse without the television cameras picking it up; meanwhile, the actors have to keep stepping discreetly over his body while continuing their dialogue every time they have to cross the set. It was a brilliant, hilarious improvisation in which at least five interlocking things were occurring at once (including, of course, the television monitors that showed the oddly strained drama in progress); Tati was playing all of them, including the Hulot corpse, and had me helpless, in stitches.

After a while he calmed down and returned to his chair. “The only trouble is,” he said, “I’ll never raise the money to make a movie that starts off with a scene like that.” The finality of that made him grow somber again, and after toying with a few more conventional gag ideas, he sank back into his Slavic gloom and looked out the window for a while. Then he smiled and said we’d done enough work for the day, and I took the bus back to Paris.

End Note:

*It’s intriguing to note that in Sight and Sound‘s recent Top Ten poll (Autumn 1982), the two critics apart from myself who list PLAYTIME, Gilbert Adair and Vmcent Canby, are both English-speaking, as are the two others who list CÉLINE ET JULIE VONT EN BATEAU (David Thomson and Robin Wood) — another French comedy about the joys and perils of spectatorship.

— Sight and Sound, Spring 1983