The following was commissioned by and published in Frank Tashlin, edited by Roger Garcia and Bernard Eisenschitz, Éditions du festival international du film de Locarno, 1994. — J.R.

“According to Georges Sadoul, Frank Tashlin is a second-rank director because he has never done a remake of You Can’t Take It With You or The Awful Truth. According to me, my colleague errs in mistaking a closed door for an open one. In fifteen years’ time, people will realize that The Girl Can’t Help It served then — that is, today — as a fountain of youth from which the cinema now — that is, in the future — has drawn fresh inspiration ….To sum up, Frank Tashlin has not renovated the Hollywood comedy. He has done better. There is not a difference in degree between Hollywood or Bust and It Happened One Night, between The Girl Can’t Help It and Design For Living, but a difference in kind. Tashlin, in other words, has not renewed but created. And henceforth, when you talk about a comedy, don’t say ‘It’s Chaplinesque’; say, loud and clear, ‘‘It’s Tashlinesque’.“

Jean-Luc Godard’s review of Hollywood or Bust in the 73rd issue of Cahiers du cinéma (July 1957) is founded on a frank prophecy, only a small part of which has come true. In 1972, not many people realized the degree to which The Girl Can’t Help influenced the modern cinema and not only Godard; and in 1994, alas, even fewer respond to the name Tashlin, much less “Tashlinesque”. Thus the fact that the adjective meant and continues to mean something at once specific and multi-faceted requires some explication — including an explanation of why such a definition becomes necessary.

I’m speaking here not only of the contemporary memory-hole into which most film history has disappeared — the amnesia which requires an explanation for many younger viewers of what, say, “Godardian” means — but of a historical breach of faith that took place in the 1970s, when Godard’s prophecy was meant to be fulfilled. Why it wasn’t fulfilled, despite a ratification of Godard’s 1957 prediction in many of his own films of the 1960s — such as references to cartoons in Band Of Outsiders and Made in USA, the vending machine in Alphaville, and the cocktail party (color filters and all) in Pierrot le Fou, not to mention the washing machine in Bertolucci’s Partner — can be attributed to several interlocking failures and resistances:

1. The development by Jerry Lewis of a writing and directing style both derived from and distinct from Tashlin’s (in its relative freedom from topical satire and its greater reliance on nonsense), beginning with The Bellboy in 1960, that subsequently confused the matter of who Tashlin was and what “Tashlinesque” meant for spectators and critics on both sides of the Atlantic.

2. A decrease in the relative impact, energy, and satirical inflection of Tashlin’s work, which arguably started around the same time.

3. A critical resistance to Tashlin in both England and the U.S., usually coupled with resistance to Lewis as well, and often accompanied by a preference for the more conservative and conformist wit of Blake Edwards. (Indeed, by the late 1970s, when a certain Francophobia had overtaken much of Anglo-American film criticism — during the same period when the New German Cinema had come to replace the French New Wave as the vanguard art cinema movement — a good many commentators who wished to disparage French film taste merely had to evoke French enthusiasm for Lewis in order to score points; on this level of pseudo-discussion, making any distinction between Lewis and his mentor was hair-splitting for anyone but specialists).

4. By the late 1970s, the ascent of a more verbal and literary style of American comedy as represented by Woody Allen and Mel Brooks that made Tashlin even less fashionable.

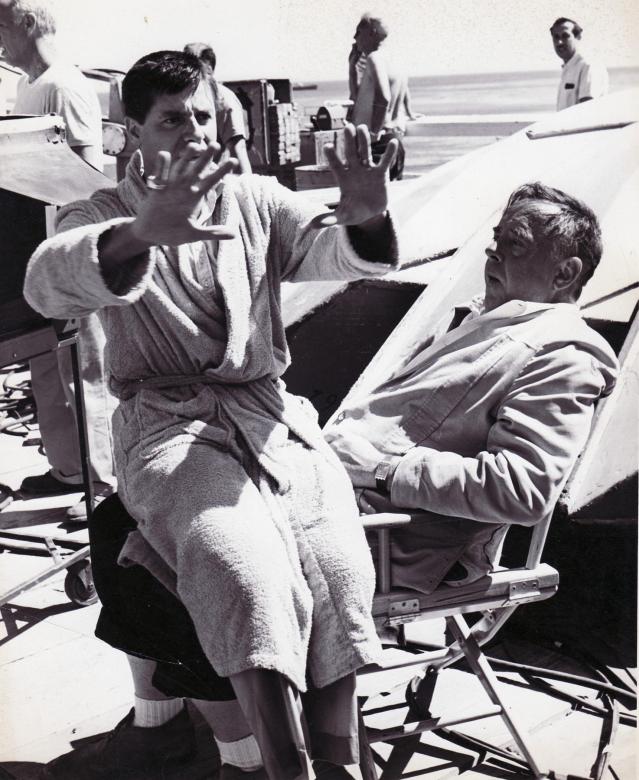

This is not to suggest that over the 37 years since Godard’s prophecy, the term “Tashlinesque” was not used; only that the use of such a term became increasingly esoteric. To cite two examples from my own experience: at a 1972 press conference in Cannes held by Jerzy Skolimowski after the screening of his King, Queen, Knave [see above still] — a free-wheeling adaptation of Nabokov that I had liked and most of my colleagues had detested — I asked him what kind of importance Frank Tashlin (who had just died in Hollywood only a few days before) had for him, noting the presence of what I believed to be a Tashlinesque style in his film. Skolimowski’s reply was that he wasn’t sure he knew who Tashlin was, but if his intuition was correct, he didn’t take my comparison as a compliment.

I committed a similar faux pas the following year in a less public forum, while working on a translation of a film treatment by William Klein. I remarked to Klein that his 1968 feature Mr. Freedom struck me as Tashlinesque. In this case, Klein was fully aware of who Tashlin was; Artists and Models had recently been re-released in Paris, and Klein noted with amusement having seen Jacques Rivette first in line in front of a cinema where it was opening, “as if it were Potemkin” – -but he, too, didn’t regard my intended tribute favorably.

What did I mean when I called these two otherwise very different films Tashlinesque? In both cases, I was thinking about a deliberately dehumanized form of expressionism in the cartoon-like demeanor of the major characters that had bitter satirical overtones, loud primary colors that also suggested cartoons and comic books, and a spirited vulgarity that comprised a kind of bittersweet response to infantile American energies run amok. In the case of King, Queen, Knave, I was thinking of the hysterical adolescent sexuality of John Moulder Brown, the hero — comparable to that of Lewis — as unleashed by Gina Lollobrigida, who played his stepmother, and whose sexual glamour — comparable to that of Jayne Mansfield — was equally hyperbolic. In the case of Mr. Freedom, the cartoon styling was somewhat attenuated by other devices suggesting puppet theater and the satire was clearly agitprop, but the comic exaggerations and pop iconography assigned to actors, costumes, and settings seemed to stem from a related impulse. In both films, moreover, a deliberate and disturbing confusion between human and android came to the fore in the final shots — a life-size Gina Lollobrigida doll produced at the end of King, Queen, Knave; the eponymous hero of Mr. Freedom revealed as a broken robot at the end of Klein’s film — that literalized certain implications of Tashlin’s style in a way that gave additional political and ideological weight to his caricatures, without the mitigating Hollywood-style humanism that invariably crept into his own features. In both cases, it appeared to me that the cruelty of the satire was above all a reading of Tashlin, a forcing to the surface of certain implications that in Tashlin’s comedies had figured mainly as dark and latent possibilities.

In order for me to have made this comparison, however, a certain abstract leap of faith was necessary, and one which ignored the immense ideological, social, and practical breach between Hollywood and art cinema. This was a leap that Godard’s filmmaking in the 1960s had already taken — a utopian form of appropriation and inclusion that declared that cinema was cinema, that Preminger and Mizoguchi, Cukor and Bergman, or Tashlin and Skolimowski could sit at the same table in a Godard film, and freely converse on an equal footing. It was much the same impulse, in a way, that suggested that Marxist-Leninists, Maoists, and ordinary factory workers could all arrive at the same conclusions, in the same language.

It is said that the inability of many to make this leap was — and is — a matter of taste: the key term used against Tashlin and factory workers alike is “vulgarity,” and class implications may be equally operative in both usages. If Raymond Durgnat in 1969 could spot the same “mixture of despair and acquiescence” in both Tashlin and Warhol, most of his Anglo-American contemporaries were too busy segregating the two into the mutually exclusive categories of entertainment and art to ponder the salient parallels. Thus the “coldness”, distanciation, and ironic playfulness that critics cited in defense of Warhol’s sophistication as a dandy and artist were all regarded as negative factors in relation to Tashlin — proof even of his alleged corruption as an entertainer. While Warhol was declared an acute social analyst who perfectly understood the art market (i.e. the class to which he catered), Tashlin was branded as a man with a breast fixation who was too implicated in what he was satirizing to qualify as a serious artist. Different strokes for different folks — and most of the people whom Tashlin addressed didn’t read auteurist criticism.

In conclusion, it seems to me that “Tashlinesque” can mean one or more of five different strains in the contemporary cinema which I will list below, with appropriate examples from the films of other directors, and stretching “contemporary” to include everything over the past half-century:

A. Graphic expression in shapes, colors, costumes, settings, and facial expressions derived from both animated and still cartoons and comic books. The most Tashlinesque Tashlin film in this respect is probably Artists and Models. Some of the most notable examples by other directors include Rowland’s The 5,000 Fingers Of Dr. T. (1953), Frank’s Li’l Abner (1959), Losey’s Modesty Blaise (1966), Jessua’s Jeu de massacre (1967), Resnais’ I Want To Go Home (1989), Beatty’s Dick Tracy (1990) and Lee Myung-sei’s Korean comedy My Love, My Bride (1991).

B. Sexual hysteria – -usually (if not invariably) grounded in the combination of male adolescent lust and 1950s’ notions of feminine voluptuousness. Examples in the work of others: Wilder’s The Seven Year Itch (1955), Sidney’s Bye Bye Birdie (1963) (one of the few depictions of female adolescent lust), Lewis’ The Ladies Man (1961), Donner’s What’s New Pussycat? (1965), Allen’s What’s Up, Tiger Lily? (1966), Axelrod’s Lord Love A Duck (1966), and Reiner’s The Man With Two Brains (1983).

C. Vulgar modernism. This term, usefully investigated by J. Hoberman in a 1982 essay, is described as a “popular, ironic, somewhat dehumanized mode reflexively concerned with the specific properties of its medium or the conditions of its making”. It seems appropriate that Tashlin’s first solo feature, aptly titled The First Time, should open explicitly under the sign of Tristram Shandy — arguably one of the earliest avatars of vulgar modernism — with the narrator describing the physical and emotional state of his parents prior to his own birth, i.e. the conditions of his own making. Hoberman cites eight other Tashlin features as examples, as well as several Tex Avery cartoons, Chuck Jones’ 1953 Duck Amuck, and some of Tashlin’s own early animation. Live action examples by others would include Potter’s Hellzapoppin’ (1941), Sturges’ Sullivan’s Travels (1941), Lewis’ The Patsy (1964), Quine’s Paris When it Sizzles (1964), Mel Brooks’ Blazing Saddles (1974), Albert Brooks’ Real Life (1979) and Modern Romance (1981), and Allen’s The Purple Rose of Cairo (1985).

D. Intertextual film references. Properly speaking this could be subsumed under C, but the plethora of such references in Tashlin’s cinema suggests that it deserves a special category of its own. Examples: Walker’s Road To Bali (1952), Truffaut’s Tirez sur le pianiste (1960), Malle’s Zazie dans le métro (1960), all of Godard’s features before 1968, Ross’ Play It Again, Sam (1972), Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau (1974), Mel Brooks’ Spaceballs (1987), and Zemeckis’ Who Framed Roger Rabbit (1988).

E. Contemporary social satire: products, gadgets, fads, trends. Perhaps the richest and most neglected vein of the Tashlinesque. Examples: Sturges’ Christmas In July (1940), Chaplin’s A King in New York (1957), Tati’s Mon oncle (1958), Renoir’s Le Déjeuner sur l’herbe (1959), Marc O’s Les idoles (1968), Itami’s Tampopo (1986), and Clifton Ko’s Hong Kong comedy Mr. Coconut (1989).

More than any other, this latter category accounts for what continues to keep “Tashlinesque” a radical term: the capacity to aestheticize while ridiculing the giddy excesses of consumer culture, from rock and roll to groceries to comic books to Marilyn Monroe. While Godard and Warhol made this process more self-conscious, Tashlin clearly plowed the field that they went on to cultivate. Broadly speaking, the uses of French rock music in Une femme mariée, teenage publicity in Masculin féminin, movie lobby displays in Made in USA, detergent boxes as high-rises in Deux on trois choses que je sais d’elle, and little red books as décor in La Chinoise are as brazenly Tashlinesque in their intricate love-hatreds as the Tashlin lampoons of Monroe via Jayne Mansfield, Sheree North, and Tuesday Weld — stylizations that cleared the way for both the various “Marilyn” paintings of Warhol and, much later, many of the music videos of Madonna. In this respect at least, Godard’s prophecy may have been more correct than he knew.

— adapted from contribution to Frank Tashlin, edited by Roger Garcia and Bernard Eisenschitz, Éditions du festival international du film de Locarno, 1994; slightly revised in 2009