From Cinema Comparat/ive Cinema, Volume 1, No. 1, 2012 (a Spanish academic online journal, available at http://www.ocec.eu/cinemacomparative/pdf/ccc01.pdf). I’m reposting this after fixing a broken link. The Introduction to this long out-of-print book can be found here.– J.R.

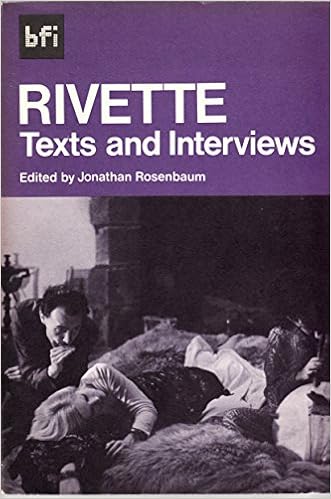

“Rivette in Context” had two separate incarnations, occurring a year and a half apart. The first consisted of 28 programs presented at London’s National Film Theatre in August 1977, to accompany the publication of Rivette: Texts and Interviews — a 101-page book I had edited for the British Film Institute while still working on the staffs of two of its magazines, Monthly Film Bulletin and Sight and Sound, in 1976.

This book included a polemical Introduction by me and translations — most of them by my London flat mate, Tom Milne — of two lengthy interviews with Rivette (one in 1968 that was centered on L’amour fou, the other in 1973 that was centered on the two separate versions of Out 1), three key critical texts by him (“Letter on Rossellini,” 1955; “The Hand” [on Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt], 1957, and “Montage” [with Jean Narboni and Sylvie Pierre], 1969), and a brief, undated proposal of his from the mid-1970s (“For the Shooting of Les Filles du Feu” — the latter was the working title for a projected series of four features, never completed, that was subsequently retitled Scènes de la Vie Parallèle). The book concluded with a detailed “biofilmography” and a virtually complete bibliography of Rivette’s critical texts published between 1950 and 1977 and his major interviews (two dozen in all).

During the final portion of my five years of living in Paris (1969-74), before I moved to London to work at the BFI, I had become friends with Eduardo de Gregorio (1942-2012), Rivette’s principal screenwriter during this period, and thanks to our friendship, I had attended many private screenings of Céline et Julie vont en bateau when it was still a work print (albeit in its final edited form). I had subsequently interviewed Rivette, along with Gilbert Adair and Lauren Sedofsky, in my Paris apartment for the September-October 1974 issue of Film Comment (1); then, after my move to London, I had organized an elaborate reportage on the shooting of Rivette’s Duelle and Noroît in Paris and Brittany, respectively — carried out by myself, Gilbert Adair (a mutual friend of de Gregorio and myself at the time, as was Sedofsky) and Michael Graham (de Gregorio’s partner) — which appeared in Sight and Sound’s Autumn 1975 issue. (2)

The programs at the National Film Theatre, shown over the entire month of August, were Voyage to Italy; Kiss Me, Deadly; Bonjour Tristesse; Gertrud; Paris nous appartient; L’amour fou; Machorka-Muff & Othon; Made in U.S.A.; Tashlin’s Artists and Models; Spione; The General Line; La réligieuse; The Life of Oharu; Out 1: Spectre; Céline et Julie vont en bateau; The Seventh Victim; House of Bamboo; Hawks’ Monkey Business; The Connection; Red Psalm; Lang’s Beyond a Reasonable Doubt; Daisies; Duelle; Trafic; Moonfleet; French Cancan; Fellini’s Roma; Noroît. (The world premiere of the latter film — immediately after a screening of Duelle, with Rivette in attendance — had already been held at the National Film Theatre in late 1976.) I selected the films and wrote notes for the series, but was unable to attend any part of it because I was living at the time in San Diego, having moved there from London earlier that year.

The second incarnation of “Rivette in Context”, which I was able to attend — at New York’s Bleecker Street Cinema, in February 1979 — was more ambitious, largely because it lacked the institutional muscle of the British Film Institute and therefore required much more improvisation. Although an effort was made to sell copies of Rivette: Texts and Interviews at some of the screenings, in the Bleecker Street Cinema’s lobby, this second series was designed more than the first as a critical and polemical intervention rather than as a simple accompaniment to the book.

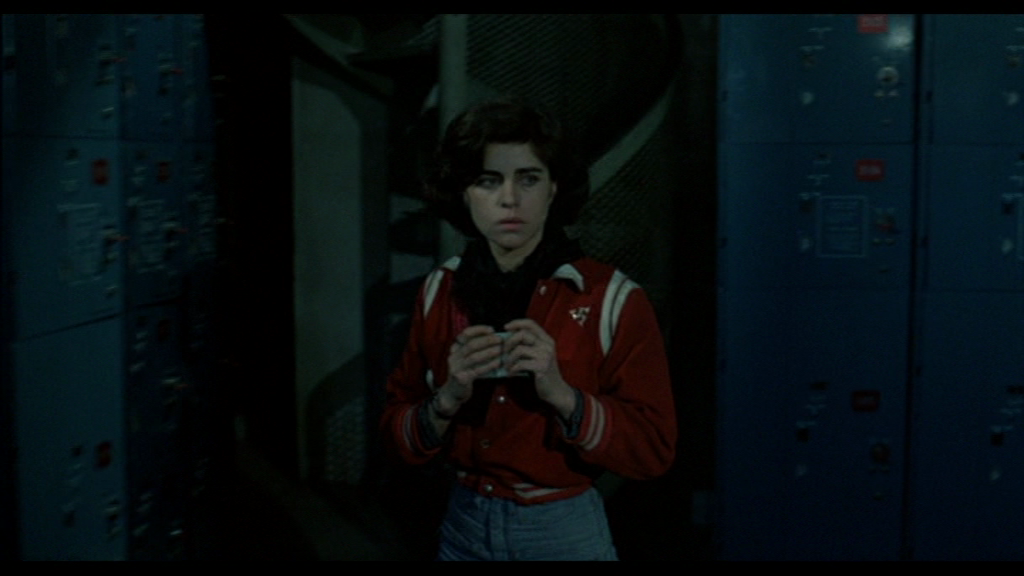

In this case, the 15 separate programs, listed here in order, all had thematic titles. “Masterplots”: Out 1: Spectre; “Critical Touchstones (Myth & History)”: The Miracle, Le mépris, Not Reconciled, Mediterranée; “Critical Touchstones (Documentary & Fiction)”: Something Different, The Edge, Le horla; “The City as Labyrinth”: Orphée, Paris nous appartient; “Women & Confinement”: Angel Face & La réligieuse; “Theatre”: L’amour fou; “Clarke & Rouch”: The Lion Hunters, Les maîtres-fous, The Connection; “Movie Doubles”: Party Girl & Gentlemen Prefer Blondes; “Dizzy Doubles”: Céline et Julie vont en bateau; “A Plunge into Horror”: The Seventh Victim, Cat People, I Walked with a Zombie; “Menace & Mise en scène”: Duelle;“Fantasy & Conspiracy”: Moonfleet & House of Bamboo; “Treachery & Mise en scène”: Noroît; “I am a Camera”: Lady in the Lake & Dark Passage; and, finally, a “Special Preview Screening” (projected but later canceled) of Merry-Go-Round, Rivette’s latest feature, which eventually surfaced much later at the Museum of Modern Art, with Rivette in attendance (as he had been at the NFT’s Noroît premiere, but not at either of the incarnations of “Rivette in Context”).

I can’t guess how much this second program might have affected the reception of Rivette’s work in the U.S., apart from four extended press reviews it received; these were by Roger Greenspun, Andrew Sarris, David Sterritt, and Amy Taubin. The first two were mostly skeptical about Rivette but gave more mixed reviews to the programing concept behind the series. (Sarris devoted an entire page of the Village Voice to his misgivings about Rivette, coupled with his overall support for the program; the prominence of his column undoubtedly helped the series from the standpoint of publicity far more than the other three articles.) Sterritt, writing in the Christian Science Monitor, mainly supported both Rivette and the series, although he had misgivings about the quality of some of the films (e.g., Lady in the Lake, The Edge) and some of the prints of the Hollywood features, plus the fact that the two Pollet films (both U.S. premieres) were unsubtitled. Taubin in the Soho News was largely skeptical about both the program and the concept behind it: “Rivette is an interesting director, a director for whom I have more sympathy than any one of his films deserve, but why should he be the first director chosen by Bleecker St. for this kind of examination. Why not ‘Bresson in Context’?” She went on to complain, “Rosenbaum simply scheduled 20 of the films Rivette mentions as having influenced him,” and then criticized both Rivette and me for minimizing the importance of Feuillade on Rivette’s work by excluding him from the series. (Although I had considered including Juve contre Fantômas — an hour-long section of Fantômas that was at that time the only work by Feuillade available in the U.S. — I decided against it after concluding that Les vampires, which remained inaccessible at the time, would have been far more relevant. I should add that I responded to Taubin’s remarks with an angry letter that was published, along with an equally angry rebuttal from Taubin.)

I can no longer recall whether or not Jackie Raynal actually succeeded in acquiring a print of Jean-Daniel Pollet’s Le horla from France for our series, but I do vividly recall her doing just that for Pollet’s Mediterranée — which was the first film she had ever worked on as an editor and therefore had a particular personal importance for her. In this case, I had included the film specifically because of Rivette’s reference to it in his interview about Out 1, which appeared in Rivette: Texts and Interviews; and I would also concede to Taubin’s charge that the inclusions of The Seventh Victim, Moonfleet, and Lady in the Lake had been prompted by Rivette having used these films as explicit reference points for Duelle, Noroît, and Merry-Go-Round, respectively, even to the point (if memory serves) of screening prints of each film for members of his cast and crew.

But the main inspiration for the series, even I hadn’t fully realized this at the time, was undoubtedly Henri Langlois and the eclectic mixes of his programs and schedules at the Cinémathèque Française, which I firmly believe eventually inspired the eclectic on-film film criticism of Godard, Resnais, Rivette, Truffaut, and Moullet — not so much the referential “hommages” of their American disciples (e.g., Woody Allen or Brian De Palma alluding to the Odessa Steps sequence in Eisenstein’s Potemkin), which add nothing to our critical understandings, as the ways that these filmmakers’ own directorial styles critically alter ourperceptions of the films and aesthetics they absorbed: how Godard treats German Expressionist cinema in Alphaville, how Resnais savors the looks and atmospheres of 50s MGM Technicolor musicals in Pas sur la bouche (to cite a much later example of this practice) and other forms of Hollywood glamor and suspense in the much earlier L’année dernière à Marienbad, how Rivette applies Truffaut’s analysis of the doubling of shots and characters in Shadow of a Doubt in the narrative construction of Céline et Julie, how Truffaut autocritiques his own politique des auteurs in La chambre verte, or how Moullet lovingly parodies Duel in the Sun in Une aventure de Billy le Kid, to cite a few examples among many others. (I hasten to add that Resnais is not usually accorded any status as a film critic because he never published reviews, but I would argue that his filmmaking practice reflects precise critical readings of other films that are quite distinct from his jokey “hommages” (such as blown-up-images of Alfred Hitchcock inserted unobtrusively, almost secretly, Marienbad and Muriel), which are much closer to the cinephiliac references of Allen, Bogdanovich, De Palma, Scorsese, et al.

No less crucial was Langlois creating particular critical contexts in which, for example, Preminger could “converse” with Mizoguchi and the German Lang could interact with the American Hitchcock, another trait that marked the films of the nouvelle vague — creations, one might say, of a previously nonexistent critical “space” in which such disparate figures could mingle and instruct one another. Above all, it was these critical “contexts,” created specifically through programming choices, that had inspired my own. The perception, for instance, that the improvisational and freewheeling shooting methods of Out 1, suggested in certain ways by those of Renoir and/or Rossellini, had been dialectically countered by the more rigorous editing principles of Lang or Hitchcock, was a critical concept derived directly from Rivette’s own discourse in his interviews.

From today’s perspective, I believe that the principal limitation of my allusions to this discourse through my programming selections was that they were in effect abbreviations of broader arguments that needed entire written texts as well as films in order to be clearly expounded and illustrated. If I were organizing such an event today, I would try to find some way of incorporating all of the following texts in order to illustrate the principle of rhyming shots: Hitchcock’s Shadow of a Doubt, The Wrong Man, and Family Plot; Truffaut’s “Un trousseau de fausses clés” (3);Godard’s “Le cinéma et son double” and Chapter 4a ofHistoire(s) du cinéma;and Rivette’s Céline et Julie vont en bateau. Postulating such a combination of texts and screenings may seem as utopian now as it was over three decades ago, but a utopian concept of what criticism could and should be was central to “Rivette in Context”.

End Notes

1. Available online at http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/?p=28298

2. Available online at http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/?p=24458 and http://www.jonathanrosenbaum.net/?p=28300

3. For a gloss on this key text and the possible reasons why it isn’t better known, see

https://jonathanrosenbaum.net/2021/05/a-possible-solution-to-a-mystery/?

BIBLIOGRAPHY

ADAIR, GIlbeRt, GRAHAM, MIcHAel, ROSeNbAUM, JONAtHAN (1974). Les Filles du Feu: Rivette x4. Sight & Sound, no 44, pp. 195-198.

NARbONI, JeAN, PIeRRe, SylvIe, RIvette, JAcqUeS

(1969). Montage. Cahiers du cinéma, no 210, March, pp. 16- 35.

RIvette, JAcqUeS (1957). La main. Cahiers du cinéma, no 76, November, pp. 48-51.

RIvette, JAcqUeS (1955). Lettre sur Rossellini. Cahiers du cinéma, no 46, April, pp. 14-24.

JONATHAN ROSENBAUM

Graduated at Putney and studied literature at Bard College. Professor at the University of California (1977) and visitant Professor at the Art History Department of the Virginia Commonwealth University (Richmond, Virginia, 2010-2011). Film critic at the Chicago Reader from 1987 until 2008. His books incluye, amongst others, Moving Places: A Life at the Movies (1980), Film: The Front Line 1983 (1983), Placing Movies: The Practice of Film Criticism (1995),

ROSeNbAUM, JONAtHAN (1974). Jacques Rivette. Work and Play in the House of Fiction: On Jacques Rivette. Sight & Sound, no 43, pp. 190-194.

ROSeNbAUM, JONAtHAN (1997). Movies as Politics. Berkeley and Los Angeles. University of California Press.

ROSeNbAUM, JONAtHAN (1977). Rivette: Texts & Interviews. London. British Film Institute.

Movies as Politics (1997), Movie Wars: How Hollywood and the Media Limit What Movies We Can See (2002) and Essential Cinema (2004). He has also edited books on Orson Welles and Jacques Rivette. During his stay in Paris, in the early 1970s, he worked as an assistant to Jacques Tati.