From Sight and Sound (Autumn 1975).

I was shocked to learn of the death of Gilbert Adair, a close friend during the mid-70s (when both of us were living in Paris, and for some time later, after I moved to London ahead of Gilbert). This collaborative article, which I instigated, assigning the middle sections to Gilbert and to Michael Graham (also, alas, no longer alive), is being posted or reposted in memory of our friendship. (With Lauren Sedofsky, Gilbert and I had also already collaborated on an interview with Rivette the previous year, which was posted here yesterday.) And because of the unusual length of this article, I’ll be running it in two parts; the second half, with sections by me and Michael Graham about Noroît, will appear a few hours from now. — J.R.

In theory, from the vantage point of early spring, it would go something like this: four movies to be shot consecutively, each one an average-length feature to be filmed in three weeks; editing to begin after the fourth is shot, the four films edited in the order of their successive releases. For practical reasons, shooting order — 2, 4, 1, 3 — has to differ from editing and release order…In practice, from the vantage point of late July, the three-week schedules had to be abandoned once the separate films grew — in scale if not in running time — and Jacques Rivette is currently preparing to shoot the third film, No. 1 in the series. Some preliminary ground rules: each covers the same 40-day Carnival period extending from the last new moon of winter to the first full moon of spring, when goddesses are permitted commerce with mortals. These ‘daughters of fire’ — the title is taken from Nerval — come in two varieties, Daughters of the Sun (fairies) and, Daughters of the Moon (ghosts). No. 1, a love story, will have a mortal (Albert Finney) as hero, a ghost (Leslie Caron) a heroine. No. 2, a film noir, pits a ghost (Juliet Berto) against a fairy (Bulle Ogier) while each searches for a diamond that can keep her alive past the allotted forty days leaving three mortal female victims in the wake. No. 3, a musical comedy conceived for Anna Karina and Jean Marais, will have a fairy playfully switching around the identities of three mortal men. No. 4, a Jacobean tragedy, sets two vengeful ghosts Geraldine Chaplin, Kika Markham) against a pirate fairy (Bernadette Lafont), with plenty of perishable mortals in between. Some goddesses may reappear in separate guises in later movies, but each film is designed as a discrete unit. Live music from on-screen musicians will figure increasingly from one film to the next, in instrumentation as well as frequency. For the first time since La Réligieuse, all the shooting will be in 35mm, in the same wide-screen ratio (1 x 1:85) as the former. By necessity, the following reports are not of completed works but of tournages. Rivette’s working methods change radically from one project to the next, making predictions extremely difficult; and from its inception, Les Filles du Feu has been in a state of constant evolution. Thus many of the projections here and below are subject to revision, and the events described relate less to the films themselves than to particular stages in their developments.

1

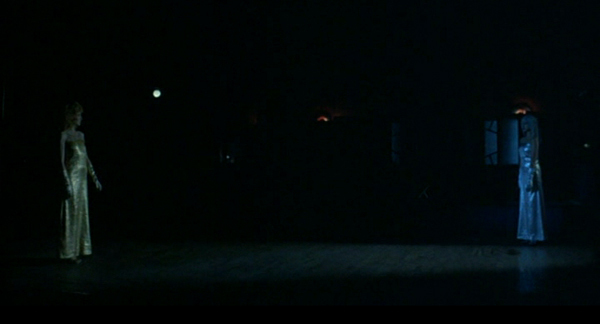

April 14, Paris: Arriving late morning in Parc Montsouris, not far from Cite Universitaire, I come upon Rivette and his crew shooting part of the final sequence of L’Oeil Froid (a tentative title later replaced by Viva, which is no less tentative [1]), a sort of duel at dawn between Hermine Karagheuz (Lucie, a mortal) and Juliet Berto (Leni, a ghost) in front of an imposing tree. Lucie is holding out an enormous diamond that glows an improbably bright and bloody red, a trick contrived with batteries and invisible wires. ‘Red Magic,’ Rivette says to me in English, laughing, between takes. Both actresses are veterans of Out 1 and Spectre, Rivette’s most extended experience with what he calls ‘improvisation sauvage‘, but this time they aren’t improvising at all. All 27 sequences in the film have been mapped out in advance by Rivette and a scriptwriter, Eduardo De Gregorio, and the latter and Marilu Parolini are writing the dialogue every day only hours — sometimes minutes — before the players commit the lines to memory and deliver them for the cameras; if adjustments are made, it is Rivette alone who makes them.

There’s no dialogue in the present shot, and while Karagheuz glints menacingly at the camera in red jacket and jeans, Berto is standing out of camera range in a flowing cape, looking quite a bit like a ghost. Some of her appearances, like those of the other goddesses, will be heralded by gusts of wind, in interiors as well as exteriors, and theoretically her features will gradually grow whiter and paler over the course of the film while her lips steadily redder, until this climactic confrontation, when she assumes some of the pallor of the phantom princess in Ugetsu.

In some ways, the relaxed and congenial mood of the crew suggests a family reunion. Karagheuz has acted in two previous Rivette films, Berto in three and Bulle Ogier four; Parolini worked on L’Amour Fou, De Gregorio on Céline et Julie vont en bateau and the unproduced Phénix, and both collaborated with Bertolucci on the script of The Spider’s Strategy; the project has the same producer, Stéphane Tchalgadjieff, as Out 1 and Spectre; the script girl worked on L’Amour Fou, and the stills photographer is Berto’s sister. During lunch in a nearby bistro, Rivette, quickly goes over the afternoon’s handwritten dialogue, alters the order of two sentences, gives it back to De Gregorio so final copies can be written out for the actors, and then continues to talk about the movies he saw over the weekend. A rarity among directors, he keeps up with cinema as religiously as a daily critic, and not even a tournage will necessarily encourage him to swear off entirely. The story is told that on one occasion, when The Golden Coach first opened in Paris, he spent an entire day in the cinema, from first show to last — testimony to a kind of dedication and endurance that may not be unrelated to the running times of his last four films. While the crew sets itself up in the Labyrinth of the Jardin des Plantes — a spiral footpath which leads up a hill overlooking the promenade and greenhouse — for an afternoon of retakes, De Gregorio describes a few of the cinematic reference points at work in the film. Before shooting started, The Seventh Victim, perhaps the most elliptical and troubling of Val Lewton’s films, was screened for members of the cast and crew (three months later, for the next film, Moonfleet will be projected for comparable reasons), and film noir conventions are constantly kept in mind. Tomorrow’s shooting in the adjacent greenhouse is partially prompted by The Big Sleep, just as a future meeting in an aquarium is, suggested by The Lady from Shanghai; and Kiss Me Deadly seems to be regarded as a locus classicus throughout.

The present scene is an earlier meeting between Leni and Lucie which will occur roughly halfway through the film; in principle, a series of short dialogues separated by jump cuts as they meet and walk along parts of the spiral path and elsewhere. Initially filmed near the beginning of shooting, this is being partially redone with different dialogue now that Rivette has had a chance to look at the rushes and rethink the mise en scène. The time will be dusk, the location rather dark under a network of branches: like the other ghosts in the tetralogy, Leni functions best at night, just as Viva, along with the other fairies, prefers the brightness of day.

By late afternoon, a light rain has started, but the crew goes on shooting well past official break-up time, in the cramped quarters of the curious little gazebo on top of the hill. There hasn’t been enough time to secure permission from the park authorities to use this location, which Rivette selected on the spur of the moment, so there’s a slightly tense and watchful mood as the camera makes 360 pans following Leni and Lucie round the small perimeter of the raised platform.

April 15: In the sweltering greenhouse, Viva (Bulle Ogier), the sun-goddess, meets Jeanne (Nicole Garcia), another mortal, known as Elsa when she works as ticket-girl in a dance hall. Will this scene between blondes ‘double’ the meeting between brunettes Leni and Lucie in the former’s shadowy domain in the Labyrinth, which is planned to transpire two sequences earlier? Ogier, outfitted in a grey velvet pants suit with pink scarf and blouse, black gloves and stick the later concealing a mean-looking blade — greets Jeanne in a film noir trenchcoat streaked with a yellow scarf. But if the actresses’ costumes are correspondingly ethereal and earthy, the expressions playing over their faces often provides a strange contrast and counterpoint — a paradox which seemed to surface at odd junctures in yesterday’s shooting as well, when Lucie would suddenly take on an unearthly look or Leni would begin to seem human.

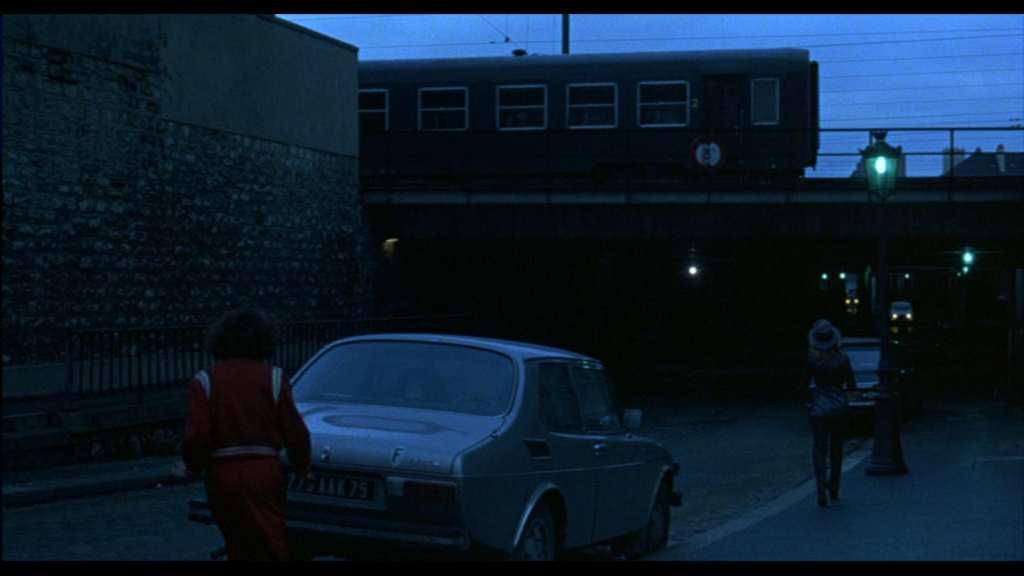

Once again, the characters walk while the talk, and the camera is frequently on the move as well. William Lubtchansky — cameraman on Les Violins de bal and husband of Nicole, who edited L’Amour fou and Out 1 with Rivette — is having to manoeuvre some fairly tricky tracks and hand-held turns in the narrow passages between the plants. At one point, he has to be pulled backwards by assistants and then swung around to one side while the women approach the parallel paths which converge at the tip of a botanical island, then criss-cross their positions. This shot, too, is a retake of something filmed three weeks ago, and among the many changes, it now lasts 50 seconds instead of 103. Jeanne begins all her lines with phrases from Les Chevaliers de la Table Ronde — Cocteau is being quoted fairly often in the dialogue — and continues in an increasingly dreamy and glassy-eyed manner while unseen birds chatter wildly around her. By the end of their exchange, she’s gazing at the ceiling like a somnambulist: ‘Elsa…Jeanne? Elles sont mortes. Il ne reste que moi. Invulnerable. De fer.‘ After lunch, the crew drives to the edge of Paris, a grey neighborhood near Avenue d’Ivry –‘Rivette likes it because it’s depressing,’ someone cracks, although the assistant director, Bertrand Van Effenterre, picked the spot. A poster displaying a pop singer is covered with tarpaulin for the background of the first shot in the scene where Lucie follows Viva. The composition, Lubtchansky notes, is a Delvaux; Viva, some distance away, descends a steep flight of steps and approaches the camera while Lucie stealthily slinks around corners and moves after her in sudden angular bursts, making staccato zigzag motions as she darts from one hiding place to the next.

The next shot occurs on an even bleaker adjacent street with decrepit turn-of-the century houses and peeling paint, Viva and Lucie approaching from some distance again. But this time something extraordinary happens: a portly middle-aged woman with hair the color of ashes and sawdust, unaware of the presence of actors and crew, wanders down the street after the take begins and stoops over to peep through a ma– slot in a tin fence — a Lumière subject suddenly come to life. She steps back a bit, looks around: will she notice the camera on one side, the approaching actresses on the other? Rivette can barely contain himself; everyone holds his breath. She looks through the slot again, and just as she passes, Karagheuz has the ingenious idea of incorporating her as a prop, a temporary shield to hide behind…Lubtchansky declares it a successful take; certainly it’s an unrepeatable one. The woman wanders off, still oblivious to the movie she’s stumbled into, and I step over to the mail slot to see what she was peering at. The answer: nothing at all.

It’s already starting to drizzle and grow dimmer when Lucie and Viva proceed down opposite sides of an underpass, away from the camera; by the time they’re crossing a footbridge towards the camera over some railway tracks, it’s mise en scène under a driving rain, Lubtchansky and camera protected by waterproof plastic, everybody else getting soaked. If improvisation in this movie is being denied to the players, it’s none the less figuring in the writing, directing and spirited scampering about, the unwitting extras and the elements themselves.

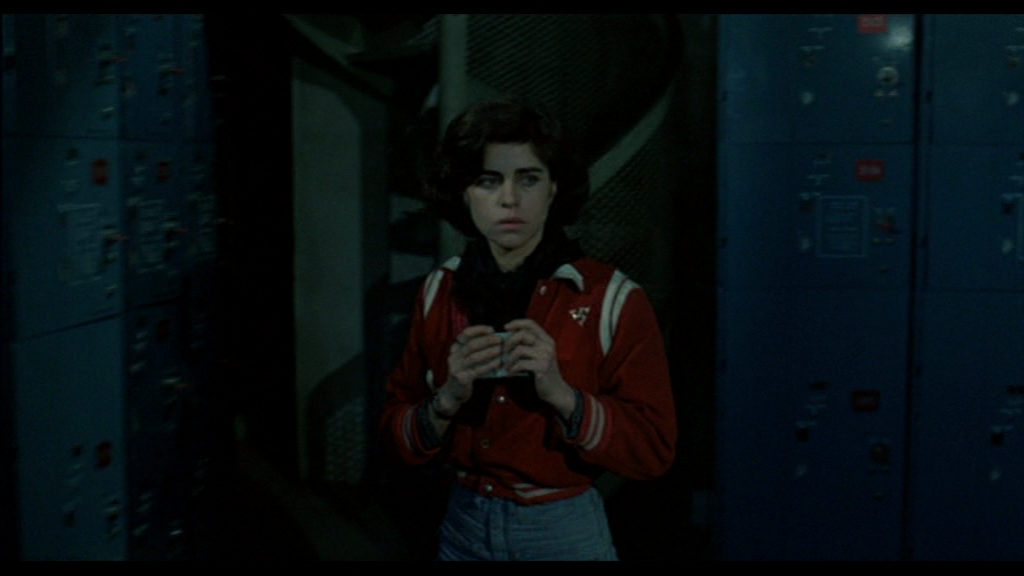

April 16: Very elaborate tracking in a dingy, labyrinthine comer of Gare d’Austerlitz occupied by baggage lockers — this location selected by Rivette. The camera moves 30 feet to the left when Lucie enters, following her in medium shot to a locker. A static, closer shot shows her opening it with a key, taking out a tiny box and shaking it (the diamond is inside). Shot three, starting in a close-up, has the camera precede her over 46 feet of curving tracks as she returns the way she came; after she leaves the shot, it tracks forward again as Viva descends a spiral staircase directly across its line of vision. All in all, one very small and complicated piece of a very complicated plot.

Between shots, Rivette amuses himself by cheerfully reading aloud from a copy of Truffaut’s recently published criticism, which someone has brought along. To translate freely: ‘Fellini shows [in 8 1/2] that a director is first of all a man whom everybody worries from morning to night by asking questions which he can’t or won’t answer. His head is filled with small divergent ideas, impressions, new-born desires, and one requires him to deliver certainties, precise names, exact figures, indications of time and place.’ J.R.

2

I offer here no more than the random gleanings of a casual observer, as I am convinced that any attempt at analysis on my part would be dishonest and as fraught with booby-traps as the undergrowth of criss-crossing wires on the floor of a film set itself. I am not a frequenter of films on location, but what most impressed me about my visit to Viva was the sense of there being two distinct narratives that I might follow: that of the film proper and that, even more intricate and mysterious, of the filming, a disjointed narrative that would nevertheless, and sooner than I anticipated, gather its own momentum, with its own dramatic highlights, comic relief, and so on. A film outside a film, as one says: a film within a film. It is in the Hotel Meurice, a sumptuous old pile on the Rue de Rivoli and the terminus of an exceptionally circuitous route that has taken Rivette and his actors from the Jardin des Plantes to a working-class dance hall, from an aquarium to a gambling den, that I watch part of the shooting. There, camping in one of its mirrored salons, is a largely young and blue-jeaned crew, busy adjusting the arc lights, testing the boom that is perched over the set like a fishing rod, or lugging the camera, and William Lubtchansky, who is sitting on it, along heavy tracking rails. And there, at the far end of these rails, Rivette himself sits, cross-legged and patient, in the midst of this monstrous train set.

The shot being set up is somewhat complicated. Elsa (Nicole Garcia) nervously enquires at the reception desk for a certain Monsieur Pierre, the clerk offers her a seat and sets off in search of the elusive guest. After picking up this little scene in long-shot, Lubtchansky’s camera, followed closely by Bulle Ogier as Viva, all in pearl-grey velveteen and as radiant with supernatural health and malice as the other girl is deathly white, begins a slow track to where Elsa is seated, passing a vacant chair beside hers, then turning, no less abruptly than Elsa does herself, to reveal that same empty chair now magically occupied by Viva, the actress having neatly slipped herself into it at the very instant it left the frame. As I watch this shot eerily turn first-person en route and twist its own tail with the minimum of fuss, I can’t help thinking of certain equally beautiful ‘shots’ in sport: a hole in one, or one of those apparently effortless manoeuvres in billiards, thrilling even to one ignorant of the game. After four or five takes, Rivette is satisfied, the clerk returns to his desk, and the two actresses to their own reflections. It is during preparations for the following scene, in which Viva wickedly attempts to worm from Elsa the nature of her relationship to the mysterious Monsieur Pierre, that I have a chat with Jean Wiener, who improvises at the piano throughout the film. In the 1920’s, Wiener played the piano at the Boeuf sur le Toit, was friend to Cocteau and Stravinsky, ‘discovered’ jazz and in a general way, the seventh member of Les Six. Obviously delighted to be once more part of an avant garde, if so unlike that of his own generation, he confesses that though fully concurring in the idea of improvising during a tournage, his merry-go-round (or melancholy-go-round) waltzes and foxtrots being recorded simultaneously with the dialogue, it has puzzled him to see in the rushes, scenes in which he himself ‘un vieux monsieur chauve au piano‘ is perfectly visible. He is even more bemused by Rivette’s explanation: that, given the complexity of certain camera movements, it was the simplest solution. As the shot is rather long in setting up in part due to the omnipresent mirror creating unwanted sources of light, in part to Rivette’s increasingly evident concern with pure mise en scène, Wiener installs himself at his piano, tinkling out medleys of Gershwin and Kern that add to the strong silent-film atmosphere already present in the palmy decor of the Meurice, haunted by the ghosts of aviators, spies and sleeping Madonnas.

It is Nicole Garcia’s scene, and she carries it off brilliantly. Drawn out by Viva, Elsa admits that she is not at all what she seems, that her name is not Elsa, but Jeanne, that she was merely ‘befriended’ by Pierre, and that she is nothing more than a hostess in a cheap dancing (this said with head cupped low in hands)…a dancing (pause) (turns from the camera-lens to stare directly into Viva’s face)…Le Rhumba! Her monologue, like most of the script, was written just a few hours before the take, and is not only in the choice of the word ‘rhumba’ that I recognize the amusing, unsettling ‘touch’ of the film’s Argentinian co-scenarist, Eduardo De Gregorio.

Garcia, a newcomer to the bande a Rivette, is all nervous tension, barely controlled, in striking contrast to Ogier, whose mannish dress and suave style suggest, to this observer, some odd mixture of George Sand and George Sanders. Here as elsewhere, Lubtchansky’s camera is on the move, tracking into Elsa’s ghostly features as if to force the confession out of her. It has become obvious that, in terms of camera movement, this (and the other three chapters of Les Filles du Feu) will be by far Rivette’s most considered work date, with two principal poles of reference: Mizoguchi for the long takes and Ophuls, of course, for the frequent tracking shots. What this will mean in the context of the completed work is a mystery to me and, I suspect, to some of those most intimate with the project. I am no longer as astonished as I was by the small degree to which Rivette himself appears to participate in the actual shooting. My impression is of a director whose basic decisions have been made, one of which is to employ as little as possible the kind of improvisation for which he is famous — except for the music, which may well affect the playing almost a good or bad audience will do in the theatre.

This said, Rivette remains Rivette; and the last shot that I witness, in which the two goddesses, Viva and Elizabeth — played, in a gorgeous scarlet cape, by Wiener’s daughter Elizabeth — mock the naive pretensions of mortals, is a good example of how one take will often serve as rehearsal for the next, the actresses accumulating or discarding detail at such a dizzy rate that, once it is over, I find I have no clear collection of what piece of business is or not in the final take.

The set is a table for two in one of the smaller salons, a table laden with ice cream, champagne and petits fours. Around it the two young women gaily disport themselves – popping corks, feeding each other smeary chocolate eclairs, and making curious ‘vroom vroom’ noises a la Kiss Me Deadly – with Wiener’s sprightly accompaniment turning the whole thing into musical chairs. The first take, however, is wretchedly flat, the second a clutter of cute details. It is only with the third that the actresses start to scent out the scene’s real possibilities and its rhythm, so much so that they cease, quite spontaneously, to block each other in front of the slowly tracking camera. Rivette does not guide them in either verbal or mimetic fashion, but between takes he will venture to advise against certain inventions and for others, so that, in the end, the shot will doubtless conform to all his first feelings about it.

Whatever else it may be, a film is also the record of its own tournage. In Rivette’s case, the film set becomes a theatre of imponderables, which shape the result much as a sleeper’s movements will govern the nature of his dreams; and from the evidence of interviews one realizes that the only guidelines of a Rivette film are those of tournage, the idea of a definitive form, at least until editing begins, being a nonsense. In the past (L’ Amour Fou, Out 1) his overriding concern as a director has been to record the work’s gestation, which tempts me to suggest that, though the ‘legendary’ 13-hour version of Out 1 may indeed be extraordinary, it must be less so than the six-week version, i.e. the tournage. From Viva, whose camera movements are plotted out in advance but whose dialogue is written the evening before, whose actors have specific things to do but whose music is improvised, one can have no idea what to expect. G.A.

(to be continued)